Seattle Socialist :

The Workingman’s Paper

|

Report by Gordon Black

Abstract:

For ten years, this weekly newspaper was the strongest voice for

socialism in the Pacific Northwest. Edited by Hermon Titus, The Socialist was acerbic, witty, and

often sectarian.

City of publication Seattle (briefly Toledo, Ohio; Caldwell, Idaho)

Publisher Socialist Educational Union

Affiliation Social Democrat Party -

Seattle

Publication dates August 12, 1900 – August 20, 1910

Frequency Weekly and special daily

editions - 4 pages

Circulation 2000+

Cost Subscriptions 50 cents a year, 10 weeks

for 10 cents or 2 cents per issue

Business address 220 Union St, Seattle; 114 Virginia St.;

latterly 1620 Fourth Ave, Seattle. Also stated as 14 News Lane, Seattle.

Status Extensive but not complete set of newspapers

microfilmed. University of Washington, Microform and Newspaper Collections:

A2663 Editorial staff : None listed initially but beginning in 1907 when a masthead listing editorial staff appeared in the Seattle publication, Hermon Titus was the editor. (In a letter to the Post Office in 1902 Titus signed his name as “business manager.”) He stayed in the role of editor through the last existing issue of the newspaper in August, 1910. Titus was also listed in the masthead of The Socialist, published in Toledo, Ohio and during its time in Caldwell, Idaho (June, 1906 - November, 1908). According to historian Carlos Schwantes, Radical Heritage, Titus moved The Socialist to Toledo because he regarded it as the “industrial center of the United States.” Since the Toledo operation was not successful, Titus used the pretext of the Haywood trial to move the paper again – to Caldwell. Titus had ambitions of converting Idaho into the “first socialist state.” Schwantes asserted that Titus remained in Idaho a mere three months. The paper itself remained in Caldwell much longer, though it is possible that Titus himself was in Seattle. From Seattle, Titus organized free-speech demonstrations in defiance of authorities. The issue became a kind of campaign carried extensively by The Socialist. Imprisonment of participants allowed the paper to also report on the squalid conditions in the Seattle city jail, which the newspaper described as “Seattle’s black hole.” After 1910, the final year of The Socialist, Hermon Titus is listed in Polk’s Seattle Directory as the editor of Workingman’s Magazine (1911), and subsequently in 1912 as editor of The Four Hour Day. His wife, Hattie, is listed as the business agent for this publication.

In later years, The Socialist listed separate editors

for Oregon, Idaho and Washington, as well as special contributors on such areas

as socialism and science; socialism and the farmer; socialism and the middle

class. In 1909, from a list of 17 contributors and staff members, four were

women: Bessy Fiset, assistant editor; Hattie Titus (wife of the editor),

advertising manager; Mrs Floyd Hyde, contributor on socialism and the home; Lulu

Ault, circulation manager. Other listed staff included: Erwin Ault,

managing editor; Arthur Jensen, assistant editor; Ryan Walker, cartoonist; John

F. Hart, cartoonist; Richard Krueger, Washington State editor; Thomas Coonrod,

Idaho State editor; Thomas Sladden, Oregon State editor. Lineage: In 1901, the banner indicated that The Socialist merged with The New Light, a Socialist weekly founded in 1899 in Port Angeles, Washington by EE Vail. 1905 and1906 editions of The Socialist appeared in the UW collection with a Toledo address, suggesting that Titus, the named editor and a founder of the Socialist Educational Union in Seattle, moved there for a period and kept the paper going from Ohio. Since not all numbered copies are within the UW collection, it is not clear if the Seattle-based Socialist published simultaneously with the Socialist in Toldeo. With issue 298 in June, 1906, the paper moved to Caldwell, Idaho, where it published through issue 319 (November 24, 1908). Editor Titus wrote then that the newspaper would henceforth be published in Seattle. Again, numbered issues, although not complete, are sequential from Seattle to Toledo to Caldwell and back to Seattle. Apparently, the last issue came out in August, 1910.

Summary

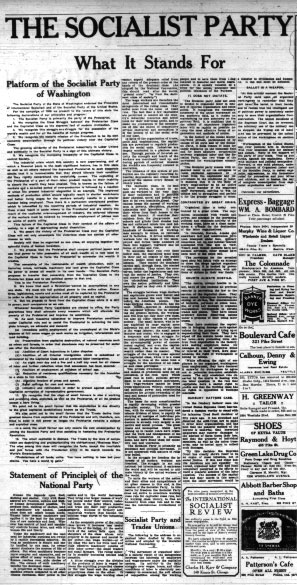

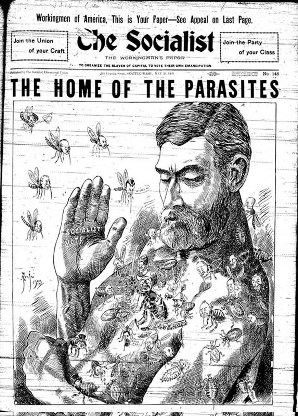

The Socialist – The Workingman’s Paper was produced by an arm of the Social Democrat Party in Seattle with the express purpose of educating workers on socialists issues and positions, and spreading news about socialism and labor union activities, especially strikes. In addition to its line of socialist propaganda, it provided news coverage of socialist candidates running (and their socialist platform) for office throughout Washington State, as well as school board races in Seattle. The level of coverage given Congressional and presidential races of 1900, 1902, 1904, 1906 and 1908 varied according to the number of socialist candidates taking part. The Socialist took seriously its claim that it was the paper for the working man, and often labeled stories of strikes as news that could not be seen in other, establishment newspapers. Where it supported socialist goals or as a way to indicate the failures of capitalism, fiction was also used in the paper. Commentaries, penned by notable socialists, including novelists Upton Sinclair and Jack London, as well as translations of socialist writings from Europe (Karl Marx’s among them) did, on occasion, almost fill entire issues. Cartoons played a prominent role in the weekly four pages of The Socialist, dominating the front page on a number of occasions. The cartoons, which were mostly well executed, included both original drawings by Ryan Walker and John Hart and those published elsewhere. Certain cartoons were used in more than once. The general tumult that accompanied socialist organizations in the US and Europe did not escape The Socialist. Over the years of its publication, it condemned anarchists, criticized the middle classes, and denounced the national Social Democrat Party. Routinely, it lambasted the Seattle Daily Times and Seattle Post-Intelligencer, the local (pro-business, pro-establishment) dailies. The financial position of The Socialist was frequently tenuous. In several issues it made direct appeals for financial support through donations or subscriptions. It appeared to be on the brink of not publishing – or claimed to – and once apologized for having fewer pages than normal. Beginning in January, 1901, following its merger with The New Light, the paper began to run advertising from Seattle merchants. Among the advertisers were the Frederick and Nelson department store, Hotel Grand, several laundries and a bicycle manufacturer. Selected extracts of coverageElectionsThe state of Washington has given a Socialist percentage much above the average in the United States, the equal of Massachusetts, twice that of New York and probably exceeding that of California. Comrades, shake! The Socialist, November 25, 1900

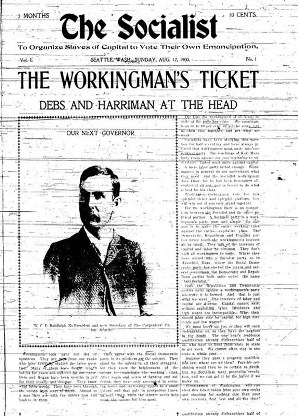

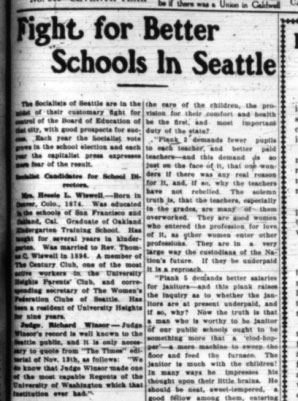

As a newspaper propagating the position of the Social Democrat Party, The Socialist provided coverage of Social Democrats running for office at any level from city and county positions to Congress and President. Thus, in its first year of publication, it gave front page coverage to the campaign and platform of socialist presidential candidate Eugene Debs as well as those running for local office[1]. It provided a full reporting of election returns from throughout Washington state, starting with the first year of publication. An estimated 3-percent of the voter turnout went to Socialists running for all state offices in 1900. A style of upbeat coverage of socialist candidates’ performance typified The Socialist’s writings of election results, even when showings at the polls were rather modest. When local results did not support the propaganda of The Socialist, it would use socialist victories from elsewhere in the US and even Europe to indicate that socialists could win elections. The socialist mayor of Haverhill, Mass., John Chase, was held as an example of what could be achieved. This was reported in the issues of November 25 and December 2, 1900. Two local mayoral candidates, E. Lux, running in Whatcom (now known as Bellingham) and Everett hopeful H. P. Whartenby were given front-page billing with photographs in the Dec. 2,1900 issue. In November 7, 1905, The Socialist provided a detailed breakdown of election returns from throughout Washington, as well as Idaho, Oregon and key summaries from New York, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania. The front page included a personal note from Eugene Debs thanking everyone, and giving particular praise to the Red Special band, a musical group that accompanied him on a nationwide tour. “At many points it was just what was needed to kindle enthusiasm and round out the meeting and give it the power to stir the crowd into action,” he wrote. Based on election returns in Washington for 1905, The Socialist predicted a total turnout for socialist candidates of 17,000 votes out of 200,000, compared to 10,000 in 1901. With the emergence of public education, and elections to school boards, The Socialist saw an opportunity to champion the end of child labor and provision of free education. In the 1901 Seattle School Board elections campaign, The Socialist published the following platform: 1. Enough school buildings of moderate cost to be built immediately to accommodate all, instead of costly palaces for the few. 2. More teachers, and better paid. 3. Teachers tenure permanent during efficiency. 4. Free meals and free clothing, if needed, to keep children from the necessity of work. 5. Free kindergartens for all children between three and six. 6. Free medical inspection weekly. 7. Greatest attention to be paid to primary grades. 8. Compulsory attendance of all children under 15. 9. An all-around development, gymnastic, aesthetic and moral instead of mere intellectual “cramming.”

NoteThe curious wording under point 9 may reflect some discomfort within the Socialist movement toward education by those who may have lacked formal schooling.

By way of supporting the two Socialist

candidates for school board, including Socialist Educational

Union co-founder Hermon Titus,The Socialist ran a

picture of boys sweeping the street outside a Seattle

department store. The newspaper asked: “Why do these

10-year-olds have to work from 7:30 to 6 every day?” If the

socialist candidates get elected, promised the newspaper,

those boys would be attending school – fed and clothed, if

necessary. The newspaper further urged its readers to

register to vote. In earlier coverage, The Socialist had

pointed out the 6000 discrepancy between the census figures

for school-age children in Seattle (17,500) and school

enrollment (11,000).It concluded that the children of the

poor must work. It suggested that by electing candidates

Denny and Patterson, poor children would remain in “poverty

and toil.”

Opposition to the established pressIn 1900, Seattle had a thriving and highly competitive press. According to Polk’s Seattle Directory of that year, 5 daily and 12 weekly English language newspapers were published within the city. The best funded were the Seattle Post-Intelligencer and the Seattle Daily Times, whose circulations The Socialist trailed. But that did not prevent it from taking frequent swipes at the bigger newspapers. It often lampooned the pro-business press of the city in cartoons, and editorials. Times’ publisher Colonel Alden Blethen was nicknamed “the kernel.” The Socialist took particular glee in telling its own readers that certain stories were not reported by the big dailies. In the March 20, 1903 issue, it pointed out that neither of the two dominant dailies had covered a Socialist meeting attended by some 2000 people, which The Socialist described as the biggest meeting in the city in past six months. As an alternative to the pro-business writings of the large dailies, the Socialist also acted as a contrarian, challenging assumptions on a wide range of issues, including the role of women, public ownership of utilities; Chinese immigration limits and industrialist Andrew Carnegie, who bequeathed libraries to Seattle and Tacoma. In an article titled, Good King Carnegie – But Under the Smoke and Chimneys What? The Socialist compared steel magnate Carngie to Napoleon Bonaparte. Where did the Pittsburg Iron Master get his power and wealth? By robbing the workingmen of America. Some of you say, no, he got it by honest means. We socialists say no to you, and we provide to you he got it by the sweat and blood of the men who working in his foundries. The Socialist, May 7, 1901

Where the paper most significantly differed in covering news events was in its reporting of strikes. Since most newspapers were also business enterprises that succeeded or failed on the basis of profits, most newspaper proprietors saw labor organizations through the lens of business operators. Consequently, their coverage of labor and trade unions tended to reflect this in-built bias at the turn-of-century. The exact opposite held true for The Socialist – it was not established as a profit-making business enterprise and it’s bias was to the workers and against the bosses. The Socialist provided a counterbalance (and admittedly, a self-serving one at that) to the dearth of coverage and anti-labor slant typically found in 1900-era newspapers. Labor issues

In 1903, the three major electric street railway companies on Puget Sound – The Tacoma Railway & Power Company, The Seattle Electric Company and the Interurban Company – were all owned by Boston-based Stone & Webster. Workers struck the Stone and Webster companies over union recognition and union negotiating power, according to The Socialist. Six hundred drivers, conductors and maintenance workers in Seattle alone were involved. The Socialist issued daily strike editions on March 27, 28, 29, 1903. “Workingmen unite,” is the Socialist motto now adopted by all unions. “The isolated laborer,” said Marx, “is powerless against the capitalist.” Capital knows that and will grant everything except recognition of the union. They must keep the right to hire scabs. Scabs are the death of unions. Therefore scabs must be cultivated. The Socialist, March 28, 1903

The Seattle Street Railway Employees Union faced formidable opposition, not only from the company but from strike-breakers and the city establishment. A court order was issued forbidding street railway company employees from speaking to each other and Seattle’s mayor deputized 18 strike-breakers as special policemen, issuing them each with a badge and a gun, according to the March 28 issue. The Socialist alluded to “violence, intimidation, hoodlums, riots” evidently reported by the other Seattle newspapers, and placed the blame for unspecified civil disturbance on the Mayor Humes for deputizing strike-breakers. “There was not a sign of riot in town until Humes appointed 18 scabs as special policemen and armed them with guns and a little brief authority. Every demonstration was wholly good natured. Nothing worse than a few eggs thrown. Everybody was laughing all the while. When suddenly the Times and P-I and even The Star begin to deprecate violence. . .people not on the scene believe those ‘violence’ and ‘intimidation’ – all sorts of things,” stated a front page article below a massive cartoon depicting the Seattle Electric Company as a “hog.” In contrast to Seattle, the striking carmen in Tacoma did not break ranks. However, The Socialists reported that drivers and conductors were brought in from Seattle to operate the street cars in Tacoma. The strikers in Tacoma were also faced with a court injunction forbidden them to damage Tacoma Railway Co. property, intimidate workers, persuade customers from using the street cars and even from “confederating together.” The Socialist, which carried the full terms of the injunction, dismissed it as “harmless.” “Only forbids threats and violence anyway – nothing to be afraid of.” The strike lasted just four days. Although the terms of the strike’s settlement in Seattle and Tacoma were not laid out – as far as this researcher could find – a later article in The Socialist was critical of the settlement. Under a heading, Why Strikes Fail, it described the street railway workers of having “won everything except the strike.” “The company reserves the right to employ non-union men. This means the union has no power to enforce better conditions, higher wages or shorter hours.” The newspaper goes on to say that it was because “an army of unemployed” was willing to work under any conditions that undermined the strike and forced the union to accept the conditions of the company. The Socialist suggested that a fear of being among the unemployed caused the strikers to return to work. The newspaper also criticized labor leaders – especially Messrs Harmon and Rust of the Washington Federation of Labor and Seattle Central Labor Council respectively for not providing better guidance to the “inexperienced” street car workers who had put on a “magnificent” fight. Here, The Socialist is careful to praise the striking workers – who represented both their readers and the volume of voters needed to elect socialists candidates – while singling out labor leaders for not providing the kind of support (not specified) the strikers evidently deserved. In August, 1903, the newspaper carried a story of a wage claim (an increase from 23 cents to 30 cents an hour) being pressed by the street car workers. Most of the article rounded condemned a mayoral request to arbitrate the dispute, as well as chastising the company for not granting the increase. The Socialist converted the cost of paying the increase as $137,970, which it claimed was equivalent to paying 4-percent interest on $3 million dollars. “. . .that is, they can water their stock to that amount. They can distribute blocks of stock in hundreds of thousands of dollars, up to three million, where it will do the most good. “You see what you are up against, boys? BIG CAPITAL. The only way to lick big capital is at the Ballot Box - and don’t you forget that.” The Socialist, August 23, 1903

The Haywood trialNothing stirred the editorial pages of The Socialist quite like the story of the trial in Idaho of Western Federation of Miners leader, “Big Bill” Haywood. Along with Charles Moyer and George Pettibone, the state of Idaho kidnapped Haywood in Denver and brought him to Boise to face charges involving the bombing murder of Idaho governor Frank Steunenberg in 1905. Idaho’s mining districts had been the scene of much violent strife between miners and mine owners. Perhaps sensing the importance of Idaho as the source of socialist fervor, The Socialist relocated to Caldwell (near Boise) in 1906. Or maybe the move was because of the stature of Haywood and the sensational nature of the impending trial. Hermon Titus, who appeared in the masthead of The Socialist of Toledo as editor and who evidently had relocated there from Seattle after helping to form the Socialist Educational Union, became editor in Caldwell. Throughout the trail, which started in 1907, The Socialist provided copious coverage, claiming to scoop the Seattle dailies when the not guilty verdict against Haywood was returned July 28. The newspaper issued two special “extras” to report the news and to reflect comment from the jury’s finding. In the August 3, 1907 issue datelined Seattle, a line drawing of Haywood appeared with a caption: “a future president of the United States.”

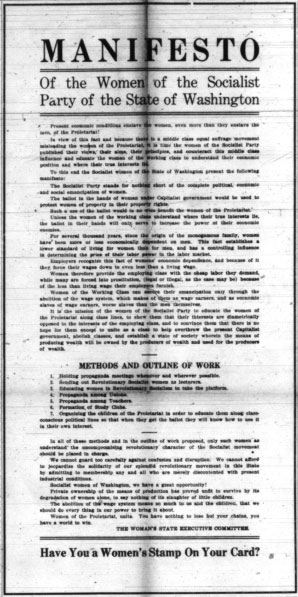

A Woman’s PlaceThe Socialist raised the debate on the issues of women in society throughout its period of publication. Although coverage of women’s did not appear with high frequency, it was visited with some regularity. In later issues of the paper, bylined articles by Bessy Fiset addressed suffrage and other issues related to women. On May 5,1901, a front page article entitled Woman, The Slave of the Wage Slave explored the concept of gender equality and economic independence for women and the right to vote. It even examined the sexism implicit among both genders towards expectation of the qualities of boys versus girls. “As a rule, before a boy has himself issued from the petticoat stage he is made to realize what a crime it is against boyhood to be termed a girl. And girls are hampered by the unnatural limitations put upon them by their mothers, more than by their fathers, in order to properly or improperly fit them for Woman’s Sphere. They must play with dolls and learn to sew, while boys play out of door games and learn to smoke and chew and swear.” The article, which supported a woman’s right to vote, made clear that a vote for a Socialist candidate would liberate women in other areas of their lives. Women of the working class can secure their emancipation only through the abolition of the wage system, which makes of them as wage earners, and as economic slaves of wage earners, worse slaves than the men themselves. The Socialist, April 17, 1909

The article called upon women to hold propaganda meetings, provide “revolutionary socialist” women for lectures, educate women in revolutionary socialism, spread propaganda and socialism clubs and organize “the children of the proletariat” and to educate them in class-consciousness. The article also asked: have you a woman’s stamp on your card? It’s not clear if this was addressed to men, or whether women could independently be members of the Socialist Party. Internal squabbles

Although disputes between its various branches dogged the socialist movement in Washington and elsewhere in the United States during the 1900-1914 period, the pages of The Socialist are relatively free of articles on such disputes. As a paper supporting the Social Democrat Party of Washington it often blurred the distinction of “socialist” and “social democrat.” It appeared to give broad support to “socialist” candidates and “socialist” causes, without necessarily identifying if those candidates or causes fitted strictly within the goals of the Social Democrat Party. In this respect, The Socialist may have been less dogmatic than other socialist newspaper or simply was disinclined to involve itself in internal disputes of the kind that wracked other newspapers. (See citation for other newspapers on this Web site.) However, there were exceptions. Early on, the paper distanced itself from the anarchy movement by roundly condemning the assassination of President William McKinley in 1901. In fact, the first issue after his death at the hands of a professed anarchist appeared with a black border. Despite this, it’s noticeable that “revolution” and “revolutionary” are still seen frequently in The Socialist in the years following the paper’s condemnation of the McKinley assassination. Although it never explained in its pages how the revolution would be achieved (by the ballot box is implied, given the coverage of election and socialist candidates), use of the term brought dissension that surfaced in the pages of the paper in the summer of 1909. Following a state convention of the Socialist Party (the ninth annual), national committee member Emil Herman wrote a front-page article critical of the state party official who lead maneuvers to silence certain local chapters at the convention. It accused W. Waynick, temporary state secretary of the party, of being manipulated by “rank middle class opportunists” in silencing the representatives of 54 locals at the convention and “destroying the Revolutionary Socialist Party of this state.” A follow-up article the next week – upon publication of the convention minutes – further accused Waynick and others of gagging the revolutionary socialists and passing rule-changes that limited the existence of locals within cities. This, the article explained, was designed to get reformists back in power in Seattle. “Reformists,” it must be assumed, were of the middle-class stripe opposed by the newspaper. The Workingman’s Paper does not seek to form a separate party opposed to other working-class parties. It supports the UNION of Wage-Workers. . . the immediate aim of the Workingman’s paper is the same as that of all other really proletariat organs, namely: Formation of the proletariat into one class, overthrow of the bourgeois supremacy, conquest of political power by the proletariat. The Workingman’s Paper, January 1910

On October 4, 1909, The Socialist proclaimed in a front-page article: Socialist Party Turns Populist. The article cited the recent decision by the national organization of the party to amend the wording of “general demands” laid out by the Socialist Party. Those included the collective ownership of railroads, telegraph, telephone and land. The national committee removed “land” from its list of demands, a move opposed by the Washington State delegation. Further divisions opened up locally over the possible inclusion of bankers, ranchers, lawyers, college professors and others as members of the proletariat. The division between what was described as a “one-class party” versus a “two-class party” was covered in the October 9, 1909 Socialist. Financial position

|

Click to enlarge

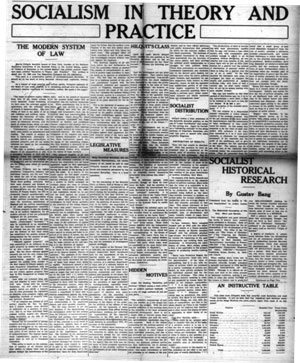

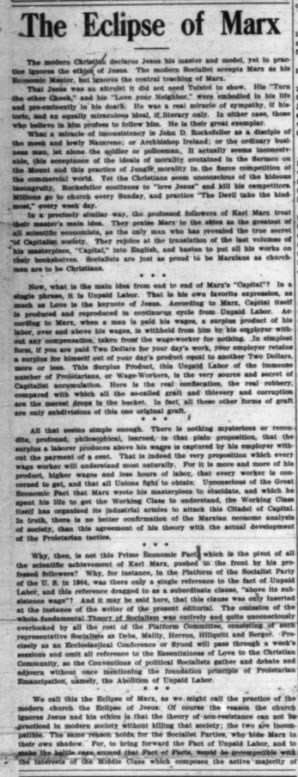

Seattle News The Socialist contained many articles about issues affecting laborers living in Seattle and Washington, such as the city's education system and Free Speech Fight in Spokane. National Labor News The Socialist also reported on national labor news. The arrest and trial of Western Federation of Miners leaders for allegedly murdering the former governor of Idaho prompted many articles in the paper as well as special editions. Theory The paper ran frequent articles about socialist theory, from reprinting experts from famous authors' works, to advocating their own views of scientific socialism.

|

|

copyright (c) by Gordon Black 2001 |

|

--Aug.%2018,%201906--p.1-300w.jpg)

--July%2028,%201906--p.1-300w.jpg)