Washington New Dealer

|

Report by Joshua Stecker

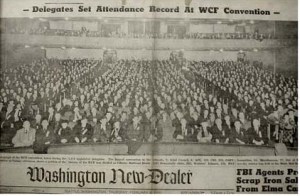

The 1930s were a turbulent time in Washington State and around the nation. The United States was slowly emerging from the Great Depression, due in part to the aggressive relief programs and legislative reforms proposed by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, collectively referred to as the "New Deal." Many Americans rallied around these ideas and organized to show their support. In Washington State, the reform-minded public found its voice in a left-wing weekly newspaper, the Washington New Dealer. The Washington New Dealer was the fifth in a series of weekly newspapers sponsored by the Washington Commonwealth Federation (WCF) and the Washington Pension Union (WPU). The WCF was a politically active organization that functioned as a left-wing caucus within the state Democratic Party from 1934 through the end of the 1940s. Its members came from a variety of social reform groups – liberals, trade unionists, grange members, and Communists. The WCF initially tried to exclude Communist Party members, but it eventually capitulated in order to form a united front of left-wing reform groups. The Communist Party, in turn, effectively used the WCF to place its members in political office, including sending WCF President Hugh DeLacy to the US House of Representatives for two terms beginning in 1945. In the end, however, the WCF was not able to survive the post-war anti-communist sympathies of the nation.[1] The WPU was born out of the WCF and the 1935 Social Security Act as an organization that championed the rights of senior citizens. The WPU outlasted the WCF and was instrumental in liberalizing Washington State's pension program in the 1940s. A good deal of the WPU's success can be attributed to its ability to function as a union, drawing support and power from both organized labor and the Democratic Party.[2] Washington Commonwealth Federation newspapers went through six name changes:

In its early issues, the paper was intently focused on electoral politics, and specifically on making Washington a model New Deal state. The September 1938 primary election garnered most of the paper's attention as New Dealers celebrated sweeping victories in the state Democratic Party.[3] On a national level, the Democratic Party remained divided on the issue of Roosevelt's New Deal. The debate was the highlight of the Democratic National Convention and was well documented in the New Dealer.The paper also found a political punching bag in conservative Democratic Governor Clarence D. Martin. The New Dealer attacked Martin for using the old age pension lists to send out mailers promising bigger pensions if he were elected – promises that were soon forgotten.[4] The paper also led the charge in hounding Martin into open hearings on the State's social security fund. It helped organize a 5,000 man march on Olympia demanding that Republicans and "unworthy" Democrats stop trying to reform and restrict the State's pension program.[5]New Dealer columnists were not above name-calling either. Writer, radio personality, and Executive Secretary of the Washington Commonwealth Federation Howard G. Costigan referred to Governor Martin as "the State's Biggest Crackpot" and called for a “Martin vs. the People” showdown.[6] After Martin's Social Security reform bill passed, "setting Social Security in Washington State back ten years," the New Dealer wondered: "When Do the People Eat Governor?"[7] Martin's reforms took a toll on the citizens of Washington State. Social Security Director Charles Ernst declared that all persons physically capable of working would have their benefits cancelled beginning April 1, 1939. This announcement was just in time for the paper to lead an organizing effort for a massive May Day protest.The New Dealer did have its share of victories to report. The paper outlined $14 million in New Deal improvements to Seattle in 1938, primarily in public works. New Deal Democrats also gained a large number of seats in the House of Representatives in 1938. In addition, Democrats were successful in getting out the vote to help overwhelmingly defeat an initiative that would have crippled potential strikes. And the paper relished in taunting its Republican "rival" publication, the Seattle Times, at one point calling its editors "sore losers" for their response to the New Deal Democratic presence in Olympia.[8] .In April of 1939, Terry Pettus took over the editorship of the New Dealer. Pettus became an integral figure in Washington State journalistic history for his work in furthering social causes. He founded the Seattle chapter of the American Newspaper Guild, which promptly staged the first organized strike of a Hearst newspaper at the Seattle Post-Intelligencer in 1936. The successful strike garnered national attention and forced the newspaper to officially recognize the union. Shortly thereafter, Pettus joined the WCF and turned the New Dealer into an ideal platform for his progressive views. Pettus had associated with the Communist Party for several years. In 1938, he officially joined the Party and remained a member until 1958.[9] Pettus' concern for social justice is evident in most of his writings. He seems to have changed the direction of the New Dealer from a strictly political paper to a broader, more socially conscious paper, focusing attention on the plights of persecuted people and the atrocities of capitalist business. This may be partly due to the fact that the WCF was well established in the Democratic Party by the late 1930s and felt less need to motivate its readership to political action. As Terry Pettus assumed control of the New Dealer, America's attention became fixed on the threat of war in Europe. In September of 1938, the newspaper carried a report on a speech, given by New Deal Democratic Senator Ralph Logan of Kentucky, warning that Hitler must be stopped or else he would soon occupy Canada and Mexico and attack the US from the north and south. In its November 19, 1938 issue, the New Dealer’s headlines echoed Franklin Roosevelt's denunciation of Nazi Germany's anti-Semitic atrocities. The editorial in the same issue demanded that the nation cut off all commercial interaction with Germany because the Nazis had proven to be unaffected by mere rhetoric. In March of 1939, the paper carried a story about Hitler seizing Lithuania without regard to that country's impending plebiscite.[10] And in April it reported that the Nazi Party had already spent upwards of $40 million on propaganda in the US over the previous four years.[11] Clearly, the New Dealer recognized that the Nazi agenda needed to be resisted at all costs.However, the paper was also somewhat handicapped in its anti-Nazi position because of the strong Communist Party presence in the WCF and on the New Dealer editorial board. The New Dealer was at least partly tethered to the policies coming out of Moscow. While the Soviet Union and Germany cooperated under a non-aggression pact signed in August 1939, the paper was compelled to take an anti-war stance. While continuing to denounce the evils of "Hitlerism," the paper lacked a clear call to action. The slogan "The People's Anti-War Newspaper" was carried on the masthead of each issue of the paper until July 17, 1941, shortly after Germany shattered the non-aggression pact with the Soviets and marched into Russia. The new logo became a bright, bold "V" for “Victory” over Nazi Germany. In this same issue, the WPU came out in full support of President Roosevelt's new policy of aid to Britain and the Soviet Union. The onset of World War II meant jobs were becoming available everywhere. The New Dealer, while maintaining a patriotic front, was not about to give military contractors free reign at the expense of workers’ welfare. Pettus denounced the use of the Army to break a strike at the North American Airplane Company by editorializing: “It comes as a shock to millions of patriotic citizens that the first blood spilled by the army, which is to spread the ‘four freedoms' to all parts of the world was that of an American worker striking against a wage of less than $20 a week.”[12] Another headline blared: “Gestapo tactics used on US employees!”[13] Meanwhile, a new advertisement aimed to net subscribers started appearing weekly, declaring, “Every Week! - The Truth About the War in Your New Dealer."The New Dealer changed tone yet again following the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor in December of 1941. Whereas previously the paper had balanced support for the war with critiques of specific policies, after Pearl Harbor the New Dealer poured all of its resources into unequivocally supporting the war effort. The paper started a fund to raise money for the war effort and carried a weekly graphic to track the war’s progress and to encourage people to give more. Terry Pettus even tried to enlist in the Armed Forces, but was informed that his work with the New Dealer was too valuable to be neglected. The months following the United States’ entrance into the war saw an increase in coverage devoted to one of the core causes championed by Pettus and the WCF: racial equality. The paper was sensitive to the need for equality in the booming workforce, confronting the government with headlines claiming "Negroes and Jews denied war jobs".[14] In the first issue following the Pearl Harbor attack, the paper ran a story on American troops receiving care packages from sympathetic Japanese Americans.[15] Perhaps Pettus anticipated the swelling anti-Japanese sentiment in America. However, the sense of wartime emergency ultimately caused Pettus to support Japanese internment for the duration of the war, a decision that was difficult to reconcile with to the New Dealer’s longstanding support for racial justice.The paper also highlighted workers’ contributions to the war effort. The New Dealer was convinced that the American work ethic would win the war and proudly proclaimed “The beginning of the end for Hitler, Mussolini, and Hirohito” when a memorandum from President Roosevelt to Donald M. Nelson, Chairman of the War Production Board, was made public. Roosevelt directed Nelson “to take every possible step to raise production and to bring home to labor and management alike the supreme importance of war production this crucial Spring.”[16] In between the political maneuvering of the WCF and the headline grabbing events of World War II, the New Dealer still had plenty of column space to devote to the people. The paper closely followed a variety of local labor issues and didn't shy away from making public any injustices that it learned of. In one issue, the paper carried a graphic photograph of a beaten Atlanta International Ladies Garment Workers Union striker, Joe Lee Walden, with the stark caption: "Still Happens."[17] It also celebrated when Washington became one of the first states to establish a minimum wage for women.[18] And in 1939 the paper exposed a British-run cement monopoly and covered the ensuing Grand Jury investigation while demanding that the plant's workers and the state's citizens should reap the gains of a publicly-owned cement industry.[19]While generally committed to serious social and political issues, the New Dealer was not without a lighter side. "The Upper Crust" was a weekly comic strip that featured caricatures of miserly old capitalists and their portly wives. One such illustration depicted a wealthy woman thumbing her nose at a crowd of workers gathered outside her balcony with her butler standing attentively at her side. The caption below read: "Shall I take over now, Madame?"[20] Ruthe Kremen contributed weekly "Jingles" – poems romanticizing the plight of the working man. There were also attempts to cover local sporting events, such as the Seattle Rainiers of the old Pacific Coast Baseball League, but these columns never ran for more than a few weeks before disappearing. The paper even ventured into the risqué by promoting the infamous Sally Rand and her "Dance of the Seven Veils" at the Palomar Theater.Advertisements for local businesses helped fund the paper. Toward the early 1940s, this spread into product advertisements geared toward working class males, including beer and fishing supplies. The paper also took care to coordinate its advertising policy with its politics. At one point in 1939, the New Dealer ran a series of notices reading: "WANTED ... Names. A list of pro-New Deal businessmen who The New Dealer can legitimately approach for advertising".[21] Classified ads were also a regular feature, providing readers with a marketplace for such things as automobiles and farm equipment.The Washington New Dealer chronicled a transformative period in local and national history. It provided liberal reformers and the working-class with news and information that directly impacted their lives, and it contributed to the success of the New Deal, the labor movement, the Communist Party, and the war effort in Washington State. As the voice of the WCF and the WPU, the New Dealer proclaimed the powerful message of putting the rights of working people first, a message that is embedded in Washington’s past and still relevant in its present. [1] Phipps,Jennifer, "Washington Commonwealth Federation and Washington Pension Union", Communism in Washington State History and Memory Project. [2] Ibid. [3] The New Dealer, September 17, 1938 [4] The New Dealer, September 24, 1938 [5] The New Dealer, March 4, 1939 [6] The New Dealer, November 19, 1938 [7] The New Dealer, May 13, 1939 [8] The New Dealer, November 12, 1938 [9] HistoryLink.org biography of Terry Pettus by Ross Rieder [10] The New Dealer, March 25, 1939 [11] The New Dealer, April 15, 1939 [12] The New Dealer, June 12, 1941 [13] The New Dealer, July 14, 1941 [14] The New Dealer, February 26, 1942 [15] The New Dealer, December 11, 1941 [16] The New Dealer, April 2, 1942 [17] The New Dealer, May 18, 1939 [18] The New Dealer, April 8,1939 [19] The New Dealer, April 29,1939 [20] The New Dealer, May 13, 1939

[21]

The New Dealer,

March 11, 1939 Women

|

Click to enlarge

The WCF’s 1938 political platform included planks calling for the expansion of social security, public ownership of natural resources and public utilities, and protection of civil rights. The New Dealer, as its name implied, was a staunch supporter of Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal, at least until events in Europe caused it to become more critical.

Labor

An outspoken proponent of the labor

movement, the New Dealer published this photo of a bloodied ILGWU

organizer in its May 18, 1939 issue.

Racism The New Dealer spoke out against racism in the Northwest and around the nation. This front-page story from October of 1938 highlights official foot-dragging during a local police brutality investigation. As this image from 1942 powerfully conveys, the New Dealer used Nazi racism abroad to critique American racism at home. Upper Crust The “Upper Crust” cartoons lampooning elite society and anti-labor employers were a regular feature. War and Peace 1939-1941

About Face

|

|

Copyright (c) 2006 by Joshua Stecker |

|

women040839-300.jpg)

hootenanny031942-300.jpg)

wcfplatform120338-300b.jpg)

NewDeal111238-300.jpg)

martin2,051339-300.jpg)

pettus040839-300b.jpg)

stillhappens051839-300.jpg)

negro102938-300.jpg)

lynchingwwii111242-300.jpg)

uppercrust010739-300.jpg)

uppercrust051339-300.jpg)

uppercrust121038-300.jpg)

antiwar071140-300b.jpg)

tugofwar110239-300.jpg)

wagecutting032741-300.jpg)

policeraid050841-300.jpg)

denouncesfdr061941-300.jpg)

vforvictory012242-300.jpg)

warlabor040242-300.jpg)

votedemocratic102942-300.jpg)