Portions of the following were previously published as Seth Bernstein and Robert Cherny, “Searching for the Soviet Dream: Prosperity and Disillusionment on the Soviet Seattle Agricultural Commune, 1922-1927,” Agricultural History 88 (2014): 22-44.

The Seattle General Strike of 1919 gave the city a reputation for radicalism, but even those familiar with the city's early twentieth-century radicalism are unlikely to know about the other radical Seattle--a highly successful agricultural commune in the southernmost part of Soviet Russia. In the 1920s and 1930s, it was often referred to as “the American commune.”[2] Its history provides an unusual chapter in transatlantic history and the international dimensions of US history and adds new dimensions to the history of immigration, the Pacific Northwest, and Soviet agriculture.

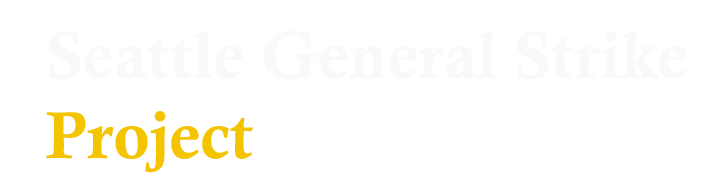

The story begins in late 1921, when a group of Americans from the Pacific Northwest organized their commune and secured permission from the Soviet Union to create their vision of rural communism. Mostly Finnish Americans with socialist sympathies, they held their first meeting in Kirkland, just across Lake Washington from Seattle, and, given the background of many of the initial members, at least some of them would have been aware of Seattle's recent radical history. During its early history, the commune was called Seattle in English, Seiatel' in Russian, and Kylväjä in Finnish. Though the initial kommunary (commune members) lacked experience with large-scale agriculture, they nonetheless made their commune the most successful and most prominent agricultural commune in the Soviet Union by the 1930s.

The Seattle kommunary were among the thousands of people from North America who immigrated to the Soviet Union in the years following the October Revolution of 1917,[3] and the Seattle Commune was one of many foreign agricultural communes that attempted to aid the new regime.[4] Passionate believers in socialism came to the Soviet Union hoping to create a world of progress and equality. Such radicals arrived with dreams of building self-sufficient communities that would form the foundation of communism on a larger scale. Such ideologically-inflected dreams of these migrants did not mean that they lacked practical concerns. Many kommunary saw the Soviet Union as a land of opportunity that could be successfully and comfortably settled. They maintained the tangible goal of finding prosperity as individuals and as members of families and communities. As they attempted to build socialism, they also tried to create the good life for themselves.

Upon settling in Soviet Russia, the members of Seattle and other foreign agricultural communes faced tremendous challenges. In the face of serious obstacles, most communes had disbanded by 1927 and some of the migrants returned to the United States. In his "Shedding the White and Blue: American Migration and Soviet Dreams in the Era of the New Economic Policy” (2013), Ben Sawyer correctly disputes the common narrative, derived from American press accounts in the 1920s, that returning socialists were overwhelmingly disillusioned with the politics of the socialist homeland. What most frequently caused foreign communes to disintegrate was the disillusionment that came when the economic realities of Soviet life could not meet the expectations that members had held.[5] Many settlers continued to live in the Soviet Union, still trying to build the Soviet project but in a way that was more personally beneficial.

Seattle was the exception to the pattern of agricultural communes’ disintegration. It became a model farm and remained a commune until 1940.[6] Why did it last where others faltered? Richard Stites, in Revolutionary Dreams: Utopian Vision and Experimental Life in the Russian Revolution (1989), asserts that revolutionary dreamers at places like the Seattle Commune succeeded when their ideological commitment was great.[7] Yet for many of Seattle’s kommunary, their stake in the commune was based as much in their family’s finances as in their convictions. Having sold what they had in North America, they attempted to claim a stake in the Soviet project—an investment in both revolutionary progress and their own family’s wellbeing.

This map shows the location of the Seiatel' commune in southern Russia where Seattle Kommunaries settled in the 1920s and the Republic of Karilia to which many of the Finnish-Americans moved in 1930. Click and zoom to see the current sites.

The foreign commune movement was part of the larger history of agricultural communalism and revolutionary utopianism in Russia and the Soviet Union. Russian populists of the nineteenth century looked to the peasant commune (obshchina), essentially the governing body of villages, as a model for Russian socialism. While those populists may have misunderstood the peasant commune, the idea of agrarian socialism had a powerful appeal in a country whose economy was overwhelmingly agricultural.[8] Soviet agricultural communes were partially an expression of this heritage but also had strong ties to revolutionary Marxist utopianism. Lenin and his followers believed that historical progress would inevitably lead to communism, a stage in history when the state and other existing forms of economic organization would disappear, replaced by the collective control of workers themselves. However, as leader of the new revolutionary state, Lenin took the more pragmatic path of state control over the economy—a “dictatorship of the proletariat” that he asserted would prepare the country for communism.[9] However, some Marxist idealists in the Soviet Union wanted to hasten what they saw as an historical inevitability. Their vision was communalist.[10] Organizing enterprises with collective ownership of capital and land, collective labor and collective sharing of the rewards, they hoped to achieve communism in small pockets of the countryside. Seattle’s members adhered to such dreams of communalism. Yet like Lenin, Seattle’s kommunaryalso held a strong belief in the power of technology and scientific knowledge to improve life.[11] Indeed, one of the main reasons that Lenin invited foreign settlers into Soviet Russia was the belief that they would bring technology and know-how that could help propel Soviet technology forward.

In spite of their invitation, the relationship of Soviet leaders to agricultural communes, foreign and domestic, was complicated. Communes of the 1920s were not like the collective farms that Stalin’s regime forced upon the countryside in the early 1930s.[12] A great deal is known about collectivization but much less is known about Soviet communes. The only work devoted solely to them is Robert Wesson’s The Soviet Communes (1963). Wesson agrees that communes, whose members were often politically active supporters of the regime, were attractive for Soviet leaders who wanted to bring technology, expertise, and politically reliable people the countryside. Kommunary fundamentally agreed with the mission of the Soviet Union and could, leaders believed, be advocates of Soviet power among peasants. Despite sharing the regime’s ideological understandings, their members’ ideals of self-organization and self-sufficiency were contradictory to the centralizing desires of Soviet leaders. Moreover, most peasants did not see these idealistic communes as models of modern agriculture but as culturally alien radicals.[13] Ultimately, like many of the utopian dreams of the Soviet Union’s first years, communes disappeared under Stalin as the regime proscribed a different vision for Soviet agriculture.[14] Of all the agricultural communes created in the early 1920s, Seattle seems to have survived the longest, operating as a commune until 1940.

Though Soviet agricultural communes were something of an historical dead-end, they can reveal the motivations of the revolution’s idealists. Little is known about the everyday experience of these agricultural experiments, what ambitions drove members, and what internal tensions may have pulled at their movement from within. They believed, of course, in the goal of building communism in the Soviet Union but they also wanted to achieve personal and communal benefit. Contradictory though this may seem in the post-Soviet world, Seattle’s kommunary did not see a paradox in their communalist dreams and a reasonable level of prosperity.[15]

Neither Wesson nor Stites were able to dig deeply into the life of an individual commune. Wesson’s work, the only full-scale, scholarly study of Soviet communes in English, was done at a time when he lacked access to sources that have become available since the breakup of the Soviet Union, and he did not make use of some sources on Seattle that were available at the time. He does provide excellent information on relevant Soviet statutes governing communes and on the evolving official position regarding communes, and he draws upon information from various communes to illustrate larger patterns of development. Stites presents a range of interesting information on communes, including general patterns of life within communes, but notes that historians have provided little information on the “interior life” of the communes of the 1920s and 1930s.[16]

It is possible, by drawing upon sources unavailable to, or not consulted by, earlier scholars, to reconstruct many aspects of the interior life of the Seattle commune. Many sources from the 1920s and 1930s come to us through an ideological filter, but there are other sources that speak more frankly, notably a series of letters in the mid-1920s from Enoch Nelson, a commune member, to his brother in the United States[17]; an account by Anna Louise Strong (an American expatriate and former resident of Seattle, Washington, clearly pro-Soviet though not a party member, and quite frank at times) of a visit in the early 1930s[18]; and a detailed description of a month-long stay at Seattle in the mid-1930s by an English essayist, Elizabeth Monica Dashwood, who wrote under the pseudonym, E. M. Delafield and was best known for her “Provincial Lady” satirical essays.[19] Other important sources include the still existing village of Seiatel’ itself with its local museum of photographs. interviews with descendants of the founders, and the oblast archives in Rostov-na-Donu. Harri Vanhala, a Finnish researcher, has collected an impressive set of source materials, including many in Finnish.[20] These sources make it possible not only to reconstruct many aspects of the interior life of the Seattle commune but also to understand why, among all the foreign communes established in Soviet Union, only Seattle experienced both success and acclaim, and also why the Seattle commune was considered so uniquely American.

Origins of the Seattle Commune

From 1922 to 1927, several hundred people, alone and with their families, migrated to the Seattle Commune from the United States. Moving halfway across the world to set up a farm in a country that had just experienced civil war and famine might strike some as a decision of rash idealism. Certainly the commune members’ politics attracted them to Soviet Russia. At the same time, American and Soviet economic conditions provided push and pull factors. In the United States unemployment surged during the early 1920s and politically active leftists faced discrimination and even legal action. In contrast, Soviet Russia seemed to offer a world of opportunity. It had huge tracts of fertile land and a welcoming government. Settlers saw the prospect of real ownership in a grand experiment—the chance to build a future for themselves and the cause they believed in.

The political and economic environment of the Pacific Northwest proved an important background for the Seattle Commune. The Pacific Northwest was home to a large number of immigrants from the former Russian empire, particularly Finns, among whom many had embraced socialism and had extensive experience with cooperatives.[21] In Seattle in 1919, a strike by shipyard workers erupted into a brief general strike, followed by the collapse of several unions and by an intense local Red Scare that helped to launch the national Red Scare of that year.[22] Then came a nationwide, post-war economic recession that reached its nadir in 1921 when unemployment rose above 11 percent nationwide.[23] The Seattle Post-Intelligencer reported in November 1921 that seven thousand men were walking the streets of the city, looking for work. Farmers, too, were hard hit by the recession--they were being offered less for their corn than they had to pay for coal, and some were burning their corn rather than sell it to buy coal for heating. Some banks, especially in rural areas, closed their doors.[24]

The situation in Russia was quite different. In February 1917, Tsar Nicholas II was deposed. After the brief, unsuccessful rule of liberals and then moderate socialists, Lenin and the Bolsheviks seized power on a wave of workers’ discontent in early November (late October by the calendar then in use in Russia) 1917. Lenin inherited a state that was crumbling after three years of war. The civil war that followed the revolution and lasted until 1921 further devastated the Russian economy. The disintegration of authority in the countryside led to unorganized seizures of land as peasant communities divided the estates of former nobles or simply squatted on the land. This chaos and Bolshevik grain procurement policies (an intensified version of the Tsarist government’s own grain requisition policies) combined with a poor harvest in 1921 to produce a major famine that resulted in the deaths of millions of Soviet people.[25] Disease, especially cholera, was widespread. Residents of the worst affected regions were reported to be fleeing by the thousands.[26]

In spite of the devastation—and in a sense, because of it—the young Soviet republic was attractive to some of the world’s workers. It was the only state whose declared mission was the advancement of the worldwide proletariat. For that reason alone it was a symbol of progress and a potential destination for disaffected workers. Moreover, the Soviet government was doing what it could to recruit help from international workers. This strategy was both ideologically driven and necessitated by diplomatic realities. The new Soviet state was a pariah in diplomatic circles. Soviet leaders had left the war and abandoned its Entente allies by signing a separate peace at Brest-Litovsk and refusing to pay the debts of its predecessor state. Soviet leaders' calls for foreign communists to rise up against their own governments won Soviet Russia no friends. Although the American Relief Administration provided essential aid during the 1921 famine, Lenin rightly did not expect foreign aid in non-crisis situations. As Michael David-Fox points out in Showcasing the Great Experiment: Cultural Diplomacy and Western Visitors to the Soviet Union (2012), the diplomatic isolation of the Bolsheviks forced them to look to non-governmental foreign actors (intellectuals and leftists) to lobby their countries to help Soviet Russia and to send aid themselves.[27]

This aid initially consisted of money and food but it soon took the form of workers themselves. Economic devastation and emigration drove the Soviet government to recruit foreign sympathizers to work in industry and agriculture. American newspapers reported the Soviet Commissariat of Agriculture’s appeal to “agrarians” who had left the country to return and receive “favorable terms to colonize agricultural communes.”[28] Lenin himself made public statements about the need for sympathetic foreign workers to come to the Soviet Union to build socialism. He singled out Americans as particularly desirable, stating that socialism could be achieved if each district [uezd] had its own model agricultural commune with American workers and technology.[29] In the United States and Canada, sympathizers founded the Society for Technical Aid to the Soviet Russia in 1919. In late 1921, undoubtedly in response to Soviet calls, organizations affiliated with the Society for Technical Aid began to organize collectives of devoted and skilled workers to settle in Soviet Russia. Similar societies in Germany, Italy, Czechoslovakia and other countries also began to organize settlements in Russia.[30]

Soon after, in November 1921, in response to Lenin’s appeal, Finnish Americans from a few existing communes met in Kirkland, developed a proposal for a commune in Russia, and requested to emigrate. They named their proposed commune Seattle. According to reports in the Rostov regional archive, one of the founding communes, recorded as “Finnish,” had seven members, and another, recorded as “Live,” had twelve.[31]

Harri Vanhala, who has extensively researched the history of the commune in Finnish sources, including his grandfather's letters, provides this account of the name: "The naming process is clearly documented in Finnish letters and newspaper articles. The original name was 'Seattle.' This is equivalent to other communes like 'California' or 'San Francisco.' . . . After the commune was organized a small group of Russians belonging to the Society for Technical Aid to Soviet Russia came up with the idea that they could join a Finnish cooperative before leaving. A meeting was convened to which all interested were welcome. At a meeting on July 16, 1922, it was decided to unite and that the name of the commune would be 'Seattle.' The name was transliterated into Russian as Сеятель (Seiatel'), which means sower. The Finnish version, Kylväjä, is a direct translation from Seiatel'. . . . Sower is a backwards translation of either Seiatel' or Kylväjä."[32]

The Soviet government accepted their proposal and gave them an eighteen-year lease on 4,500 desiatin of land--about 20 square miles (5,291 hectares)--deep in the North Caucasian steppe, some 100 miles (160 kilometers) south-east of Rostov-na-Donu.[33] It joined several other foreign communes in that area, including California (mostly from Los Angeles), San Francisco (made up of Molokans from that city), and Koit (Estonian-American-Canadian).[34] Stites notes that some 25-30 such foreign communes were formed, with Americans organizing the largest number.[35]

Each of these communes had to meet basic requirements set by the Soviet state. The Soviet government stipulated that foreign communes bring with them significant resources, including two years’ worth of supplies in order to survive until the settlement could become self-supporting. From the outset, Seattle was better prepared financially than the other communes in the North Caucasus, according to internal Soviet reports from 1927. The commune’s charter stated that members should contribute a minimum of $500 ($500 in late 1921 would have equivalent purchasing power to nearly $7,500 in early 2020) to join the commune, and some donated as much as $10,000. In total the collective amassed $200,000—equivalent in purchasing power to more than $3 million in 2020.[36] Besides initial provisions, the settlers purchased American farm equipment, including several tractors. After these expenditures, the commune still had a sizable emergency fund. The first members of the Seattle Commune, and other communes, were thus not only bound to their project by their beliefs but also by the large amounts of money they had invested—some families’ entire savings.

Who Were the Original Communars?

The 1924 audit report on the commune specifies that the original members were of Finnish and Russian descent and were from proletarian backgrounds, and that a majority of them were members of Workers Party, the legal, above-ground organization of the underground Communist Party. [37] According to Finnish-language newspaper Työmies, the orignal group had thirty members, twenty of whom were farmers, including three "agricultural experts," four specialists in agricultural machinery, and ten experienced in using machinery. In addition, there was one electrician, one blacksmith, one machinist, two carpenters, and one poultry farmer. There was no dairy expert among them but it was known that one would be necessary.[38] Beyond this, we know relatively little about this first group of kommunary. Somewhat more information exists about the three leaders of the commune and about the three commune members were sent ahead to find the best location for the commune: Alarik Reinikka, Clas Collan, and Hugo Enholm.

Alarik Reinikka was born in Finland in 1875 and immigrated in 1895 to Astoria, Oregon, where his brother had already settled and experienced some economic success. In 1898, Reinikka married Ida Fraki, who immigrated from Finland that year; they lived in New Astoria in 1900, by which time he was a naturalized citizen and was listed as speaking English. At first, Reinikka worked as a Columbia River fisherman in Oregon, then bought a farm near Longview, Washington, also on the Columbia River, in about 1905. By 1906, Alarik and Ida had five children. In addition to the farm, he continued to work as a salmon fisherman. In 1920, they were listed as owning a mortgaged farm near Monticello, Washington. Reinikka seems to have been part of the Finnish socialist community in Astoria.[39]

Clas Collan's father was a prominent mechanical engineer in Finland who had trouble with Russian authorities. Clas Collan completed two years at gymnasium before going to the US at age 16. He arrived in Portland in 1913 and lived at first with his uncle. Collan worked as a logger, a Columbia River fisherman, a farm worker, and a mechanic for agricultural equipment. His draft registration in 1918 showed him living in Kelso, Washington, on the Columbia River. A letter to his mother in 1920 indicates that he had suffered a financial loss in 1919 through a failed crop of cabbages and that his politics had moved well to the Left. In 1920, he was working as a farm laborer on a farm very close to the Reinikka farm.[40]

Hugo Enholm. was born in Finland in 1889, came to the US in 1910, and filed a declaration of intent to become a citizen in 1915. At that time, he was unmarried, living in Seattle in a lodging house, and working as a landscape gardener, all of which was unchanged by the time of the 1920 census.[41]

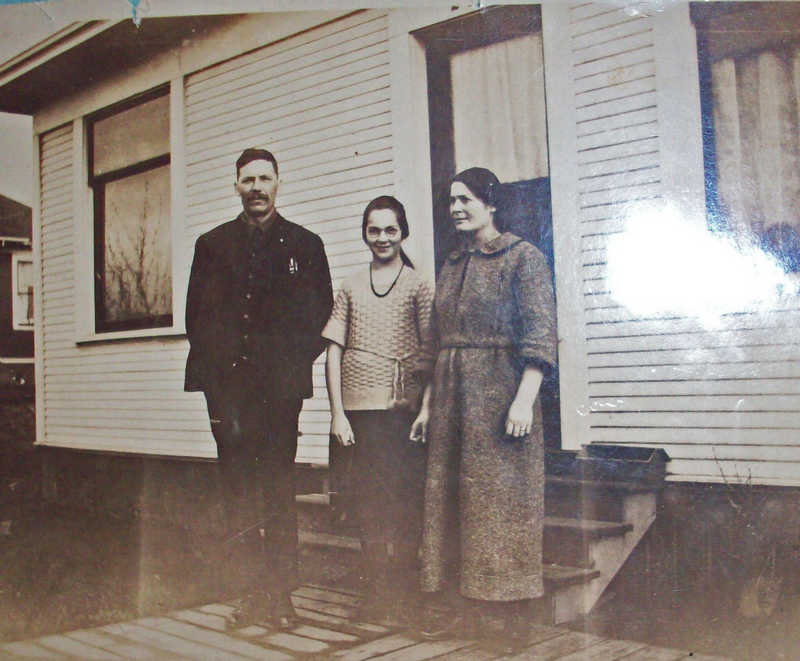

Karl, or Carl, Mattilo (nicknamed Kalle) was the first chairman of the commune. Born in 1883, son of poor Finnish farmers, he came the United States in 1903. Though a skilled blacksmith, he worked as a salmon fisherman. The 1910 census shows him living in Astoria, Oregon, as not married, and as having filed his declaration of intent to become a citizen. He was still unmarried in 1920 and lived with his brother’s family. His draft registration card from 1917 indicates that he was part of the Union Fishermen's Cooperative Packing Company, which was formed in 1896 in the wake of a fishermen’s strike broken by the state militia. Some two hundred fishermen, many of them Finnish immigrants, then organized the canning cooperative to avoid the canneries that had broken the strike. Each founding member contributed a hundred dollars (equivalent in purchasing power to more than $3,000 in 2020) to establish the coop. By 1903, when Mattilo arrived in the US, the coop had become a leading marketer of canned salmon, had a cold storage plant, and facilities in Grays Harbor and Ellsworth, Washington.[42]

Oscar Hendrickson succeeded Matillo as chairman. Born in Finland in 1881, he came to the United States in 1901. He first worked in the timber industry in northern California and then as a fisherman on the Columbia River. Like Mattilo, he was likely involved with the fishermen's cooperative and was similarly aware of the political activities of the Finnish branch of the Socialist Party of America, which had a strong presence in Astoria. By the time of the 1910 census, he was married to Sophia, also born in Finland, who had come to the United States in 1904, and they had a daughter, Ali, one year old and born in Oregon. In 1910 and also in 1920, they lived in Crooked Creek Precinct, Wahkiakum County, Washington, just across the Columbia River from Astoria, Oregon. In 1910, his occupation was listed as farm laborer, although the census also reported that they owned their own house. Listed as a “nondeclarant alien” on his draft card in 1917 (meaning that he had not filed a declaration of intent to become a citizen), he filed those papers in 1919. By 1917, he and Sophia owned their own farm, where they raised chickens and cattle, likely a few dairy cows. The 1920 census reported that the Hendricksons had a hired man to help with what was listed as a “home farm,” unlike all their neighbors who were reported to have dairy farms. In 1921, Oscar appears in the Bellingham, Washington, city directory as a laborer. Perhaps the post-war collapse of prices for farm produce had forced the family off their farm and driven them north nearly to Canada where Oscar sought work as a common laborer. He joined the Society for Technical Aid to Soviet Russia and likely had contacts with, if not membership in, the Communist Party. The family moved to the commune in 1923, with the second group of settlers.[43]

The third, and longest serving, chairman was Victor Saulit, who left a rather different trail than either Matillo or Hendrickson. Saulit was born in Russia in 1881, and listed his native tongue as Lettish, the language of Latvia. He came to the United States in 1907. In 1919, in Vancouver, Washington, just across the Columbia River from Portland, he married Julia Talp. She came to the United States in 1908, and the passenger list for her arrival listed her last previous address as a city in Estonia. Saulit’s occupation, as of 1917, when he registered for the draft, was a lumber tallyman, working for the Northern Pacific Lumber Company in Portland, Oregon. A lumber tallyman measures logs to determine the lumber content, classifies lumber, inspects it for defects in the milling process, computes the volume or length of lumber, records data, and maintains inventories. A tallyman must be able to calculate data rapidly and accurately. It was, in short, a position of considerable responsibility within the lumber mill, requiring both knowledge of lumber and skill at performing mathematical operations. Julia, in 1920, listed her occupation as tailoress, in a tailor shop.[44]

On March 27, 1918, newspapers reported that the Northern Pacific Lumber Company's Portland mill would close in a few days, as a result of a sharp decline in demand for its products due to the cancellation of wartime orders for wooden ships.[45] The next day, Saulit was arrested for refusing to stand when the national anthem was played in a theater in Portland. In Municipal Court, he and another man were fined $250 and sentenced to fifteen days in jail for disorderly conduct. Apparently they appealed, as they were released on $1,000 bond each and tried in Circuit Court in late June, when the case was dismissed. Saulit later claimed he had been arrested falsely for his failure to stand up quickly enough.[46] In 1919, Saulit was a delegate from Oregon to the Emergency Convention of the Socialist Party of America, scheduled for August 30-September 5 in Chicago. However, he was one of the many delegates who walked out and took part, instead, in the founding convention of the Communist Labor Party.[47] In early January, 1920, both Victor and Julia Saulit were among the 3,000 people arrested in the second round of Palmer Raids. The 1920 census listed their residence as the Multnomah County Jail, Portland, where they were being held. They narrowly avoided deportation as “undesirable aliens,” in part by asserting that their workers’ movement was non-violent and advocated change through electoral means.[48]

The experiences of these six men suggest some generalizations regarding the founding members of the Seattle commune. Astoria and Portland, Oregon, and the area of Washington state across from Portland seem have been at least as significant as the Seattle area as a source of kommunary, and more significant for the early leaders. All but Collan had been in the United States for a considerable time as of 1922—between twelve and twenty-seven years, long enough to become well familiar with American life. All were listed as speaking English. Several seem to have undergone economic and, in the case of the Hendricksons, geographic dislocation at the end of World War I. Matillo likely experienced a fall in demand for canned salmon as a result of the end of the war. It seems likely that most if not the large majority of those who choose to go to the Soviet Union also experienced some economic dislocation in the years following World War I. Finally, five of the six had some experience with, or at least exposure to, cooperatives and socialist politics. Mattilo, Hendrickson, Reinikka, and probably Collan all had experience with the fish canning cooperative and almost certainly had been exposed to the radical politics of the Finnish Socialists of Astoria, if they had not been an active participants. Saulit was extensively involved with the Socialist Party of America, participated in the founding of the Communist Labor Party, and was arrested, along with his wife, as a consequence. Enholm and Collan may have been typical of a different group of the original settlers--younger, unmarried, unattached, and working for wages.

Political dissent played a role in settlers’ decision to leave but an inherent part of that dissent was an economic critique that had personal implications. In 1968, Trofim Malich, an ethnic Ukrainian who was one of the first settlers, explained his decision to leave the US: “America is hell. At every step the working man sees with despair the luxuries of the rich while his brothers moan from unemployment and poverty.”[49] His explanation, though in politically correct terms for the Soviet Union in 1968, focused not on political oppression but on economic unfairness. In his mind, he was motivated to migrate by the desire to work and to be paid adequately. Saulit made a similar objection to what he perceived as capitalist exploitation of labor in the United States. During a trial of Portland’s leftist leaders in 1920, Saulit had been called to the witness stand. When the judge asked him what the Communist Labor Party considered wrong with the country, he replied, “No man in this country receives the full product of his toil if he is working for somebody else.”[50] Saulit wanted to live in a place where workers would be the primary beneficiaries of their labor. The United States seemed unlikely to become that place, but in Soviet Russia the government asserted that its goal was to address such grievances.

A survey in 1927 by the Regional Land Authority (Kraevoe Zemskoe Upravlenie—KraiZU) of all the foreign communes in the area found that the overwhelming majority of the members declared that they had signed up to help the Soviet Union. However, their desire for a non-capitalist life was also—and without contradiction—a search for prosperity. The same Soviet state survey asked why the kommunaryhad earlier left the Russian Empire for the United States. To this question, 61 of 84 respondents answered that “economic reasons” or “the search for a better life” had motivated their emigration to the US. Only nine answered that political reasons were the main factor in their move to the US.[51] During the Saulits’ 1920 deportation ordeal, Julia said that they had come to the United States “to make money” in addition to her husband’s precarious political situation in the Russian Empire.[52] The Saulits’ story of immigration was probably common—economic motivation accompanied political desires or necessities. Similarly, in moving to Soviet Russia, the settlers were not eschewing economic motives for political beliefs. Instead, their economic and political factors were tightly interwoven. Settlers believed that they would build and benefit from a land where toilers would be the main beneficiary of their own labor and collectively control their own success.

Preparations and Early Difficulties

The commune's first and most basic decision was to find an appropriate site. Reinikka, Enholm, and Collan were sent to Russia to examine the possibilities. They left in late February 1922 and found conditions in Russia extremely chaotic. Trains were not running on schedule and were seriously overcrowded. Enholm broke away from the others and headed to Karelia with assistance from Santeri Nuorteva, who had been deported from the US in 1920 and was now prominent in the Soviet Foreign Ministry. Enholm decided to remain in Karelia where he became the gardener for the Karelian government. Reinikka fell ill in St. Petersburg, and, in late May, wired the commune to ask for funds to return to the US. When the commune received Reinikka's telegram about conditions in Soviet Russia, they voted, on June 4, to disband. [53]

However, by then, Collan had managed to get to the Don region with assistance from an interpreter and guide, Isak Peskov. When they found many sites already taken, they returned to Moscow to renegotiate. Collan's letter to the commune, describing several attractive sites in southern Russia, arrived on June 5, the day after the arrival of Reinikka's telegram, and the commune members revoked their decision to disband. Collan and Reikilla, both of whom had experience with farming and farm machinery, calculated what farm equipment and other provisions were necessary.[54]

The Soviet government stipulated that foreign communes bring with them significant resources, including two years’ worth of supplies in order to survive until the settlement could become self-supporting. The Seattle commune was well prepared in this regard. The commune's initial capital of $200,000 purchased provisions and American farm equipment, including several tractors. After these expenditures, the commune still had a sizable emergency fund.[55]

Though the commune raised significant capital, many of its members were less prepared for life on the steppe. Only a third of the settlers came as families, and the rest were mostly single men.[56] Literacy was relatively high, and some brought personal libraries. Around ninety percent of the first settlers were Finns, but eleven nationalities were represented within a year, including Americans, Russians, Ukrainians, and Belorussians. Some of the commune members had been in the United States for twenty years or more and brought their U.S.-born children. The majority--perhaps the large majority--of the first settlers did not speak Russian, a problem that troubled the commune for its first decade.[57] The commune’s first and second chairmen, both Finns, were among those who did not speak Russian. Without a command of Russian, the Finns were dependent on the commune’s few polyglots to communicate with the outside world, and even with some commune members.[58]

The first settlers, cited variously as 87 or 88 in number, crossed the Atlantic and arrived at the commune's territory on October 13, 1921. Problems began from the start. Along the way, mice had infested their baggage and ruined their clothing. The commune had enough capital to replace these supplies, but in the devastated Russian steppe, far from major cities and ports, finding replacements was difficult if not impossible. More troublesome was what happened to their equipment, which had been shipped separately. The commune desperately needed their equipment to plow the tough steppe sod and plant winter wheat, but it arrived seven to eight months later, too late even to put in a large plot of spring wheat.[59]

The land also posed significant problems. The soil was renowned for its fertility, but temperatures regularly reached above one hundred degrees Fahrenheit (38° C) in the summer and dropped well below zero (-18° C) in the winter. The steppe wind is famously strong, strong enough to blow seeds away during planting. Enoch Nelson, who grew up on the Mendocino coast of northern California, arrived two years after the first group and had a negative reaction to the landscape and weather: the flat steppe was devoid of mountains, hills, forests, or major bodies of water, the summer was like that of Sacramento (very hot), and winter was “very cold.”[60] The wide variation of the climate was a difficult adjustment for the settlers from the temperate Pacific Northwest. The commune’s leaders, faced with this plot of land, initially demanded that the local land administration find them a new plot. The administration denied this petition.[61]

Several kommunary had experience farming in the US, but none had ever dealt with many of the issues facing the kommunaryin the North Caucasus. Anna Louise Strong, an American journalist who had left Seattle, Washington, to live in the Soviet Union, visited the commune several times. She later described them as “a bunch of Finnish Americans from the logging camps and logged-off farms of Washington State,”[62] but that description minimizes the group’s ethnic and occupational diversity, and ignores that various kommunary had been chemical workers, mechanics, and electricians. Thus, several of them had mechanical skills that proved vital for handling and maintaining the commune’s equipment. Hendrickson and a few others had experience with small farms. Before Hendrickson became chairman, he served as a tractor driver and what a 1935 history of the commune called a "livestock technician."[63] But none of them had ever dealt with farming on the scale that they now experienced.

The few buildings on the site when the kommunaryarrived were located at the bend of a river, in an area described by the regional newspaper as “not quite a swamp and not quite a creek, but in any case, vile and filthy”—and ridden with malaria. Seventy percent of the commune members contracted malaria in the first year, and malaria proved to be a persistent problem. In the early years, the kommunary fought it with quinine imported from the United States but then the Soviet government imposed a prohibitive duty on it. In 1924 Enoch Nelson wrote of the malaria problem, “People here are getting wise in there [sic] ways” and had found ways of avoiding the illness.[64] As the commune members built new structures, they located them as far as possible--about two miles (three kilometers)--from the original, malaria-ridden site.[65]

Commune members had some ability to deal with disease but housing proved a greater, and more long-term, problem. Their land--the former estate and horse farm of the noble Pishvanov family--included some buildings, but few were usable. One kommunarlater called them “abandoned old ruins.” The usable buildings had been taken by squatters, who had formed themselves into a collective they called Bednota(the poor).[66] Local authorities cleared them out, but, according to Strong, this caused such neighborhood resentment toward the commune that local “peasants refuse[d] to sell even a chicken to the Americans for two years.” Expecting a housing problem during the first winter, the kommunaryhad brought tents but also arranged for the women and children to spend the winter in Tselina, the nearest village.[67]

During the early years, outright danger occasionally came from bandits. The neighbors were also a source of worry. Sporadic violence and theft were regular in the post-civil war, post-famine countryside as Soviet authorities struggled to administer the enormous country. People on such Soviet-loyal communes as Seattle were supposed to help stabilize the countryside. Enoch Nelson recalled an incident in 1925 when Seattle’s leader roused several of the men in the middle of the night to serve as police backups. At a nearby cooperative farm they found two corpses, dead from gunshot wounds. The story that first emerged from the grisly double murder was that two men had robbed the farm. Later, police told Seattle’s residents that it had merely been a “settling of quarrels between bandits.”[68] Another kommunar recalled chasing off “bandits” in the commune’s first truck in the early days. Soviet authorities deployed the term bandit broadly, branding acts of political protest, intra-village retribution, and similar behavior as “banditry,” alongside its more usual sense as armed thievery.[69]

Despite these early challenges, the Seattle kommunarypersevered. By the early 1930s, they had created a highly successful agricultural commune.

Continue: Chapter 2

[1] Portions of this essay were previously published as Seth Bernstein and Robert Cherny, “Searching for the Soviet Dream: Prosperity and Disillusionment on the Soviet Seattle Agricultural Commune, 1922-1927,” Agricultural History 88 (2014): 22-44.

[2] See, e.g., Robert G. Wesson, Soviet Communes (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1963), p. 113 and throughout.

[3] Andrea Graziosi estimates that 70,000-80,000 foreign workers came to the Soviet Union before World War II. For the 1920s alone, he gives a figure of roughly 22,000. The largest contingent of these migrants were Americans who themselves or whose families had emigrated from the former Russian empire. For more on foreign workers in the Soviet Union, see Graziosi, A New, Peculiar State: Explorations in Soviet History, 1917-1937 (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2000), pp. 223-256. On American migration to the new Soviet state, see Ben Sawyer, “Shedding the White and Blue: American Migration and Soviet Dreams in the era of the New Economic Policy,” Ab Imperio, 2013:1 (2013): 65-84.

.

[4] The Seattle Commune has garnered attention from Finnish and Russian scholars. For a narrative history of the commune using Finnish sources, see Mikko Ylikangas, “The Sower Commune: An American Finnish Agricultural Utopia in the Soviet Russia,” Journal of Finnish Studies 15 (November 2011): 51-85. Russian cultural anthropologist Ivan Romanovskii presented a dissertation on the village, “Rol’ kul’turnoi granitsy v konstruirovanii lokal’nogo soobshchestva (na primere poselka ‘Seiatel’’ Sal’skogo raiona Rostovskoi oblasti),” [“The Role of Cultural Boundaries in the Construction of a Local Society (the case of the settlement ‘Seattle,’ Sal’sk district, Rostov province)”] (PhD diss., Moscow State University of Culture and Arts, 2012). Harri Vanhala, a Finnish researcher, is currently completing a book on the commune.

[5] Sawyer, “Shedding the White and Blue.”

[6] In the 1930s, the Seattle Commune served as a Potemkin village to showcase the supposed achievements of collectivization, even though it benefitted from machinery that ordinary collective farms did not own. On foreign pilgrimages to the Soviet Union in the interwar period, see Michael David-Fox Showcasing the Great Experiment: Cultural Diplomacy and Western Visitors to the Soviet Union, 1921-1941 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012).

[7] Richard Stites, Revolutionary Dreams: Utopian Vision and Experimental Life in the Russian Revolution, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989), p. 221.

[8] While peasant communes did organize some collective work on the land, their main purpose was administrative. Moshe Lewin asserts that the most important function of the peasant commune was to redistribute land among inhabitants depending on their circumstances (e.g., number of family members). Lewin, The Making of the Soviet System (New York: Pantheon, 1985), pp. 78-85.

[9] E.H. Carr, The Bolshevik Revolution,1917-1923 (London: Macmillan, 1950), I:245.

[10] As Yuri Slezkine makes clear in The House of Government: A Saga of the Russian Revolution (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2017), pp. 276-277, 340-344, during the early and mid-1920s, Soviet planners such as M. Ya. Ginzberg saw communal living as a way to eliminate bourgeois individualism, which they equated with family individualism. In communal living, "factory kitchens" were to replace "family kitchens" as a way of liberating "the female worker." Such traditional family functions as food preparation and child-raising were to be handled communally as a way of minimizing that most bourgeois of social institutions, the family. All of these concerns were reflected in the organization of the Seattle commune: communal eating, laundry, child-care, and social life.

[11] On the revolutionary dream of technology and labor efficiency, see Stites, Revolutionary Dreams, pp. 167-189.

[12] The difference between the commune and the Soviet collective farm (an artel’) is in the all-encompassing nature of the commune. Communes provided for the entire lives of its members and deducted these expenses from wages; at Seattle, housing, dining, childcare, and laundry were all communal, and most of these were required to be communal by Soviet regulations. At least some, and often many, commune workers were part owners in the enterprise. The collective farm that came to dominate the Soviet agricultural landscape after collectivization paid wages to workers, who did not own the farm and who then had to provide for their own needs from those wages.

[13] On collectivization as a conflict between the state and the peasantry, see Lynne Viola, Peasant Rebels Robert G. Wesson, Soviet Communes (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1963). Igal Halfin argues, of non-Bolshevik socialists in general, that even those who had misgivings about the policies of the Soviet state believed in the eschatological Marxist underpinnings of Soviet rule—that communism would be the inevitable result of historical progress; see Igal Halfin, From Darkness to Light: Class Consciousness, and Salvation in Revolutionary Russia (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2000). On high modernism in collectivization, see James C. Scott, Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998), pp. 193-222. On peasant rebellions, see Lynne Viola, Peasant Rebels Under Stalin: Collectivization and the Culture of Peasant Resistance (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996).

[14] Stites, Revolutionary Dreams, pp. 225-241.

[15] Writing about Finnish-American immigration to Soviet Karelia in the 1930s, Kitty Lam makes a related point that migrants to the Soviet Union “were not merely helpless victims of Soviet repression,” duped into moving to the Soviet Union and imprisoned once they arrived. Rather, many attempted to reconcile the shortcomings of the Soviet Union with their continuing dedication. Additionally, Lam points to Enoch Nelson and others as Finns who tried to improve their situations. Lam, “Forging a Socialist Homeland From Multiple Worlds: North American Finns in Soviet Karelia, 1921-1938,” Revista Română pentru Studii Baltice şi Nordice, Vol. 2, No. 2 (2010): 203-224.

[16] Robert G Wesson, "The Soviet Communes," Soviet Studies 13 (April 1962): 341-361; Richard Stites, Revolutionary Dreams: Utopian Visions and Experimental Life in the Russian Revolution (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989), esp. p. 208. Wesson’s limited sources led him to a major error when he referred to the Seattle commune as maintaining an eight-hour day; p. 177. In fact, the Seattle commune members worked very long days, as noted below.

[17] Arvid Nelson - Enoch Nelson Correspondence, Arvid Nelson Papers, Subseries 2, Immigration History Research Center, College of Liberal Arts, University of Minnesota, hereinafter, Nelson Letters. For the Nelson brothers, see the finding aid to the collection, online at http://www.ihrc.umn.edu/research/vitrage/all/na/ihrc1668.html. The experience of Enoch Nelson at the Seattle commune and later elsewhere in the Soviet Union are treated at length in Allan Nelson, The Nelson Brothers: Finnish-American Radicals from the Mendocino Coast (Ukiah: Mendocino County Historical Society, 2005).

[18] Anna Louise Strong, “Commune Seattle--A Story of Success,” Moscow Daily News, September 5, 1933, p. 2; Strong, I Change Worlds: The Remaking of an American. (1935, 1963; Seattle: Seal Press, reprint edn., 1979). For Strong, see Stephanie Francine Ogle, “Anna Louise Strong: Progressive and Propagandist” (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Washington, 1981), and Tracy B. Strong and Helene Keyssar, Strong in Her Soul: The Life of Anna Louise Strong (New York: Random House, 1983).

[19] E. M. Delafield (pseudonym of Elizabeth Monica Dashwood), The Provincial Lady in Russia (Chicago: Academic Chicago Publishers, 1985, 1998), hereinafter Delafield. The book’s title, when first published in Britain in 1937, was Straw without Bricks, and the title when first published in the U.S. was I Visit the Soviets. For Dashwood, see Maurice L. McCullen, E. M. Delafield (Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1985),

[20] Seth Bernstein conducted research in the archives in Rostov-no-Donu and traveled to Seiatel in 2008, visited the local museum, and talked with some of the descendants of the founders. He received a copy of a Finnish-language documentary film, Hailuodon kalastajasta kolhoosin johtajaksi (From a Hailuoto Fisherman to the Chairman of a Collective Farm, 1985). The documentarycontains useful interviews with some Seiatel residents who arrived there in the 1920s as children; it was translated for us by Sirpa Tuomainen. Harri Vanhala has generously shared his reseach with us.

[21] For the “Red Finns,” see, e.g., Paul George Hummasti, Finnish Radicals in Astoria, Oregon, 1904-1940: A Study in Immigrant Socialism (New York: Arno Press, 1979), esp. pp. 7-90, and Peter Kivisto, Immigrant Socialists in the United States: The Case of Finns and the Left (Rutherford, N.J.: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1984).

[22] For the Seattle General Strike, see Robert L. Friedheim, The Seattle General Strike (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1964) and Victoria Johnson, How Many Machine Guns Does It Take to Cook One Meal?: The Seattle and San Francisco General Strikes (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2008).

[23] Series Ba470, Unemployment as a percentage of civilian labor force, Historical Statistics of the United States, Millenial Edition (Cambridge University Press, 2009), online at http://0-hsus.cambridge.org.opac.sfsu.edu/HSUSWeb/search/searchTable.do?id=Ba470-477.

[24] Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Nov. 7, 1921, pp. 1, 14; Nov. 9, 1921, p. 13.

[25] Washington Post, Dec. 4, 1921, p. 69. Peter Holquist notes that Soviet grain procurement policies grew out of practices the Tsarist government pioneered during World War I; Peter Holquist, Making War, Forging Revolution: Russia's Continuum of Crisis, 1914–1921,(Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002). On the civil war on the periphery, see Orlando Figes, Peasant Russia, Civil War: The Volga Countryside in Revolution, 1917-21, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989); Donald Raleigh, Experiencing Russia’s Civil War: Politics, Society, and Revolutionary Culture in Saratov, 1917-1922, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002); and Evan Mawdsley, The Russian Civil War (New York: Pegausus Books, 2007), chs. 12-15.

[26] New York Times, Aug. 11, 1921, p. 3; Washington Post, Aug. 11, 1921, p. 9.

[27] David-Fox, Showcasing the Great Experiment, p. 17.

[28] New York Times, Oct. 15, 1921, p. 3.

[29] Antony C. Sutton, Western Technology and Soviet Economic Development, 3 vols.(Stanford: Hoover Institution Press, 1968-1973), 1:127; Stites, Revolutionary Dreams, p. 211. Later, in 1925, the chair of the Labor and Defense Council (STO), Smol’ianinov, wrote to the Society for Technical Aid to Soviet Russia that the North Caucasus, where Seattle was founded, could become the home for as many as 12,500 colonists; see Russian State Archive of Economics (Rossiiskii gosudarstvennyi arkhiv ekonomiki, hereinafter RGAE) 478-7-2140-13-18.

[30] New York Times, 15 Oct. 1921, p. 3; Antony C. Sutton, Western Technology and Soviet Economic Development, 3 vols.(Stanford: Hoover Institution Press, 1968-1973), 1:127; Stites, Revolutionary Dreams, p. 211.

[31] Audit Report of the Commune Seiatel’, November 19, 1924, State Archive of the Rostov Region (Gosudarstvenny Archiv Rostovskoy Oblasti, hereinafter GARO), Razdel 4340, opis.1, delo 333, ll. 13-15; translations by Lara King. (Russian archival materials are identified by a Fond or Razdel, Opis, Delo, and page number. There are typically abbreviated as 4340-1-333-13-15. Page numbers are not always provided.) Another file in GARO states that the commune grew out of three previous communes, a Finnish commune from Kirkland (Washington, near Seattle), a Russian commune from Seattle, and the “Live” commune from “Stumbinville.” There is no place by that last name in Washington, Oregon, or British Columbia, and it seems unlikely that a commune from Stuebenville, Ohio, would have been involved in the planning in Seattle. Perhaps the English version was Stumptown, a common nickname for both Portland and Seattle, which was mistranslated into Russian. See materials collected by the writer G.S. Kolesnikov, GARO 4340-1-333-13-15.

[32] Harri Vanhala, email to Robert Cherny, Dec. 3, 2020. Today many of the area's inhabitants are unaware of the name’s dual meaning.

[33] A deciatin is an obsolete Russian measure of land. The measurement in hectares is from Wesson, p. 113 and p. 257n37, with citation to P. Ia. Tadeusch, Amerikanskaia komuna ‘Seiatel’ (Moscow, Leningrad, 1930). Ivan Romanovskii provided the information about the duration of the original lease in an e-mail to Robert Cherny on 11/8/2009.

[34] Molokans were a Christian sect that split from Russian Orthodoxy in the 17th century. Many Molokans emigrated to North America in the 19th and 20th centuries; see Nicholas Breyfogle, Heretics and Colonizers: Forging Russia's Empire in the South Caucasus (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2005). The San Francisco Molokans all returned to San Francisco.

[35] New York Times, Oct. 15, 1921, p. 3; Antony C. Sutton, Western Technology and Soviet Economic Development, 3 vols.(Stanford: Hoover Institution Press, 1968-1973), 1:127; Stites, Revolutionary Dreams, p. 211.

[36] According to a contemporary newspaper article, the most anyone gave as dues was $5,000; see “V gostiakh u amerikantsev,” Trudavoi Don, October 6, 1923, 5. Mayme Sevander asserted that one family gave $10,000 based on her discussions with survivors and their children in the 1990s; see Sevander, Red Exodus: Finnish American Emigration to Russia (Duluth, MN: OSCAT, 1993), p. 57. An internal report from 1927 gave the commune’s membership dues at 60 rubles minimum. It also stated that the most any person (or family) gave was 12,000 rubles and that the average was 1,580 rubles; see GARO, 1485-1-488-218. Unless otherwise noted, calculations of equivalent purchasing power were calculated using “The CPI Inflation Calculator,” online at https://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.pl.

[37] Audit Report of the Commune Seiatel’, November 19, 1924, GARO, 4340-1-333-13-15; translations by Lara King.

[38] Työmies, Jan. 14, 1922; Harry Vanhala provided this citation and translation.

[39] Merle Reinikka, "Reinikka Ancestors and Descendants" (2009, online at National Nordic Musuem, Seattle), pp. 131-132; census, immigration, and directory information from Ancestry.com; additional information provided by Harri Vanhala.

[40] Harri Vanhala, email to Robert Cherny, Dec. 4, 2020; 1920 information from the census through Ancestry.com.

[41] All information from Ancestry.com.

[42] 1910 census, WWI draft registration card, and 1920 census accessed through Ancestry.com; information on the Union Fishermen’s Cooperative Packing Company from the article by Greg P. Jacob, The Oregon Encyclopedia, online at http://www.oregonencyclopedia.org/entry/view/union_fishermen_s_cooperative_packing_company/.

[43] Eero Haapalainen, Kommuuni Kylvãjã (1935), translated and provided by Harri Vanhala; 1910 census, WWI draft registration card, and 1920 census accessed through Ancestry.com; Bellingham City Directory 1921-22 (Seattle: R. L. Polk Co., 1921), p. 192. Seth Bernstein interviewed Matti Tarhalo the grandson of the Hendricksons, and made copies from the family photo album and various documents. On Astoria's radicals, see Paul George Hummasti, Finnish Radicals in Astoria, 1904-1940: A Study in Immigrant Socialism (New York: Arno Press, 1979).

[44] The 1908 passenger list, 1919 marriage license, 1920 census, and WWI draft registration card accessed through Ancestry.com.

[45] Spokane Spokesman-Review, March 27, 1918, at http://content.wsulibs.wsu.edu/cdm-all/item_viewer.php?CISOROOT=/clipping&CISOPTR=27359&CISOBOX=1&REC=18

[46] “Communist Leader Faces Deportation: Victor Saulit, Native of Russia, Has Hearing,” [Portland] Morning Oregonian, January 31, 1920, p. 10.

[47] Adolph Germer, Report of Executive Secretary to the National Executive Committee, Socialist Party, Aug. 8, 1918; accessed at http://www.cddc.vt.edu/marxists/history/usa/parties/spusa/1918/0808-germer-reporttonec.pdf; list of delegates to founding convention of the Communist Labor Party, in DoJ/BoI Investigative Files, NARA M-1085, reel 931, file 313846 (202600-779); online at http://www.cddc.vt.edu/marxists/history/usa/parties/cpusa/1919/09/0901-loebl-clpconvday2.pdf; list of delegates to 1919 Emergency Convention of the Socialist Party of America Convention; online at http://www.marxisthistory.org/subject/usa/eam/spa-conv19delegates.html.

[48] Washington Post, January 5, 1920; Saulit 1920 census manuscripts; New-York Tribune, March 17, 1920, p. 6; “Communist Leader Faces Deportation,” [Portland] Morning Oregonian.

[49] Mikhail M. Mamanov, Glubokie Korni, (Rostov-na-Donu: Rostovskoe Knizhnoe Izdatelstvo, 1968), p. 8.

[50] “Soviet Approved, Saulit Testifies. Communist Defense Witness is Cornered.” [Portland] Morning Oregonian, March 17, 1920, p. 1.

[51] Report of regional land authority about foreign communes, 1927, GARO, 1485-1-488-218.

[52] “Soviet Approved, Saulit Testifies,” [Portland] Morning Oregonian.

[53] Vanhala, summary of experiences of Clas Collan, his grandfather, received Dec. 5, 2020.

[54] Vanhala, summary regarding Collan.

[55] “V gostiakh u amerikantsev,” Trudavoi Don, October 6, 1923, p. 5.

[56] “V gostiakh u amerikantsev.”

[57] Mamanov, 13; GARO, 1390-11-90-10-12.

[58] “Kommuna Seiatel,” Salksii Pakhar, July 29, 1925, p. 3.

[59] Mamanov, p. 12; “V gostiakh u amerikantsev,” October 10, 1923, p. 5, June 30, 1924.

[60] Enoch Nelson to Arvid Nelson, June 30, 1924, folder 9, box 5, Nelson Letters. On Enoch Nelson, see Nelson, The Nelson Brothers, esp. chs. 6-14.

[61] RGAE, 478-7-2184-10-14.

[62] Strong, “Commune Seattle.”

[63] Mamanov, p. 17; Haapalainen, Kommuuni, translated by Vanhala.

[64] Enoch Nelson to Arvid Nelson, August 31, 1924, folder 9, box 5, Nelson Letters.

[65] “S kogo brat primer,” Molot, August 12, 1928, p. 3; Strong, I Change Worlds,. p. 157; Delafield, pp. 37-38. Ivan Romanovskii provided the Google map URL for the location of the settlement: http://maps.google.ru/?ie=UTF8&ll=46.421914,41.181264&spn=0.022454,0.038581&t=h&z=15 . On this map, it is possible to see a few structures at the bend of the river, labeled Сеятель Южный (Sower South), and a larger number of structures to the north, at the northern boundary of the site, labeled Сеятель Ϲеверный (Sower North). See Ivan Romanovskii to Robert Cherny, e-mail, 11/8/2009.

[66] Ivan Romanovskii to Robert Cherny, e-mail, 11/8/2009.

[67] “V gostakh u amerikantsev”; “S kogo brat primer”; Mamanov, p. 68; Strong, I Change Worlds, p. 157; Ivan Romanovskii to Robert Cherny, e-mail, 11/8/2009.

[68] Enoch Nelson to Arvid Nelson, August 13, 1925, folder 10, box 5, Nelson Letters.

[69] Mamanov, Glubokie Korni, p. 68. On the complicated divide between peasant resistance and banditry, see Viola, Peasant Rebels under Stalin, pp. 176-179; Figes, Peasant Russia, Civil War, p. 340.