To understand how the African American exodus changed history we must start with the observation that the migrants were moving into some of the most important places in America, the half dozen or so largest cities. And they were doing so precisely as those cities enjoyed their era of greatest political and cultural authority. New York, Chicago, Detroit, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Cleveland, Washington DC -- these cities, all but one outside the South, were the chief money centers, media centers, and political centers for early and mid twentieth century America, the place to be for anyone looking for access to those forms of power. Black southerners found ways to influence some of the institutions hosted by these dominant cities and through them gained leverage that eventually, over the course of decades, would be used to shift the nation's systems of racial relations and also regional relations. Key to that evolving influence was a distinct community formation that came together in big northern cities during the second quarter of the twentieth century. Contemporaries called it the Black Metropolis.

Until recently it has been difficult for historians to recognize the capacities of the Black Metropolis. The term itself largely disappeared from public discourse by the 1960s, replaced by the concept of the ghetto, a label that evokes images of distressed neighborhoods locked in poverty and lacking in resources and infrastructure. There were good reasons for this terminological shift. Activists and scholars needed to drive home the facts of racial containment and racial inequality in northern spaces. But the ghettoization model was incomplete. Concentrating on what was missing in the way of opportunities, resources, institutions, and political power, it underplayed what was present. Recent historians have found a new balance, substituting what Richard Thomas calls a "community building process" approach for the ghettoization scheme. Without neglecting the context of racism the new studies manage to suggest some of the pride and energy that went into the development of the major urban black communities.

I am going a step further and urging reconsideration of the concept of Black Metropolis. It has utility for a couple of reasons. First it calls attention to the particular setting of the principal black communities--in the major metropolitan areas of the nation. The great cities in their age of maximum greatness yielded black communities that were different than those in other settings. Second, the term Black Metropolis resurrects a celebratory terminology that African American journalists used for several decades before the sociological perspective undercut it....

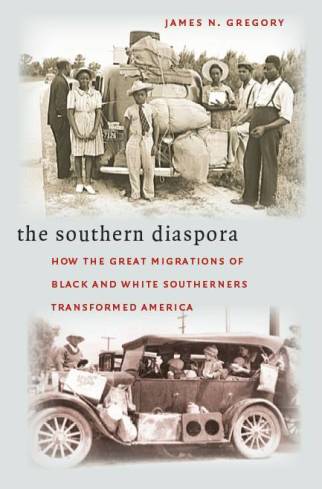

excerpts from Ch 4 "The Black Metropolis" -- The Southern Diaspora: How the Great Migrations of Black and White Southerners Transformed America (University of North Carolina Press, 2005) |

- - - -

The Black Metropolis was a product of several circumstances, including tightly targeted migration patterns which built up African American population in a select number of great cities. Eight metropolitan areas (New York-Newark, Philadelphia-Camden, Chicago-Gary, Detroit, Cleveland, St Louis, Los Angeles-Long Beach, San Francisco-Oakland) had become home to 1,003,000 black southerners by 1940, which was two out of every three southern-born African Americans living outside the South. The second phase continued the pattern. In 1970, those same cities housed 2,154,000 black southerners (and still more of their children and grandchildren) again more than two-thirds of the entire migrant population (table 4-1). Other cities---including Boston, Buffalo, Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Indianapolis, Columbus, Milwaukee, Kansas City, Portland, Seattle--also attracted black southerners in numbers that became significant over time, and there was also a certain amount of migration to the towns and rural areas of the North and West. Nevertheless the concentration of the main force of the African American diaspora into a handful of the largest and most politically and culturally significant cities was a fact of great consequence. It would be the enabling condition for much of what black southerners would accomplish in the North and West.

Important too was a particular pattern of community building, an ethos of growth and welcome that would facilitate the absorption of southern newcomers and help the emerging Black Metropolises develop new political and cultural institutions....- - - -

These dynamics enabled northern black communities to take maximum advantage of the skills and talents of the newcomers. Since there were few social barriers, migrants moved readily into all sorts of roles and positions, including community leadership roles. Indeed southerners had some clear advantages. The brain-drain segment of the Great Migration included men and women with money and entrepreneurial skills, and others with educational credentials and specialized occupational training, among them significant numbers of attorneys, writers, teachers, social workers, and ministers whose occupations encouraged the exercise of community leadership. The northern cities were going to absorb their talents and they in turn would continually transform the capacities of the Black Metropolises. The examples are many. Arthur Mitchell, William Dawson, Herbert Chauncey, Clayborne George, Charles W. White, Eugene Washington Rhodes head a long list of southern educated attorneys who quickly entered into leadership positions in Northern and Western cities during the first phase of the diaspora. Politically active southern educated doctors included Charles Garvin, Frank S. Hargrave, Ossian Sweet. Teachers, social workers, and writers: Eugene K. Jones, Ella Baker, John Dancy, Whitney Young Jr., James Farmer, James Weldon Johnson, Walter White, A. Philip Randolph, Ted Posten, John Sengstacke. Another occupational stream of this southern leadership invasion flowed through the churches as preachers, either following their flocks or responding to the calls of established congregations, moved straight into positions of prominence and influence. Archibald Carey, George Baker, Kirk Lacy Williams, Joseph H. Jackson, Leon Howard Sullivan, William Jacob Walls would be prominent on that list....

- - - -

NEW CULTURAL APPARATUS

The institutions that counted most involved politics, the subject of chapter 7. Here we want to think about cultural institutions that were associated with or antecedent to the political reorganizations of the diaspora. Because of where they settled and how their new communities functioned, African Americans developed media institutions and other cultural enterprises that had not been sustainable or perhaps even imaginable in the South. These new enterprises depended in some measure on the external resources and interactions available in the key northern cities and just as critically on the internal resources of the emerging Black Metropolis. The concentrated consumer power of tens and hundreds of thousands of wage earning families – even in the marginal job categories reserved for blacks—constituted an enormous new resource. So did the entrepreneurial energies of the men and women who thought of ways to attract and use those consumer dollars. As Adam Green has recently argued, the long held notion that the black business and professional classes were inept or irrelevant is way off the mark. The cultural apparatus of the Black Metropolis depended upon various elites—intellectual and economic—and various forms of entrepreneurship. It also depended upon forms of community and class relations that were more fluid than scholars have often assumed.

The reorganization of communications was one of the new developments. African Americans gained a national press as a result of the diaspora, newspapers and magazines that for the first time reached very large numbers of black readers across many communities. There had been publications that had tried to do this earlier, but none had ever managed a circulation to match their ambition. Now a set of weekly newspapers and monthly magazines and a Chicago based news agency would find ways to reach hundreds of thousands of readers while fixing themselves into the fabric of African American life. Roi Ottley, from the vantage point of 1943, described the press as the most influential force in black America, more important even than churches. A journalist, he may have exaggerated the last point, but not when he declared that "they have an influence in American life far beyond the imagination of most white people."

Communications theorists will recognize that in describing an influence far beyond the imagination of most white people Ottley was alluding to the changing dimensions of the black public sphere. Understanding the production and circulation of various forms of public discourse and the relationship between communications and the formation of identities and/or political action has been one of the important theoretical projects of recent years, and scholars of African American experience have begun to use these terms and tools in productive ways. Instead of taking group consciousness and political activism for granted, the concept of a black public sphere or spheres invites us to investigate the changing modes, sites, content, and capacity of public expression. Catherine Squires argues that those dimensions changed dramatically as African Americans built new kinds of communities and institutions in the northern metropolises of the early twentieth century. The Black Metropolis enabled the emergence of a unique black counterpublic with mature institutions of formal communication that were confident and secure enough to publicly argue against dominant conceptions of the group and do so using group-specific codes and styles of discourse. This was different from what she calls the enclave black public sphere of the nineteenth century that was largely hidden from whites except for carefully crafted productions by black leaders trying to appeal across the color line. Her terminology may be too emphatic. Late nineteenth century black publics did manage to circulate periodicals of various descriptions, used networks of religious organizations, women’s clubs, men’s fraternal and business organizations, and the Republican party to support national systems of communication and political action, and could be bolder and less hidden than the term enclave implies. Nevertheless, there was much that was different about the institutions, the content, and the capacities of the black public sphere that emerged in the context of the Great Migration

excerpts from Ch 4 "The Black Metropolis"

How to cite and copyright information | About project | Contact James Gregory

Follow the Project and receive updates on Facebook Facebook