The Southern Diaspora:

Black, White, Latinx, Asian, Indigenous outmigration 1900-2000

Interactive maps show the dimensions of migration from the South 1900-2000

Interactive maps show the dimensions of migration from the South 1900-2000

by James Gregory

For as long as there has been something called the American South, southerners in significant numbers have been leaving. The region itself expanded through migration as white southerners in the early 1800s carved out new states for cotton and slavery. Others moved to places that today are understood to be regionally separate from the South. White out-migration grew especially heavy in the two decades after the Civil War, with many leaving for farming opportunities and others heading for the Norths big cities—New York, Philadelphia, Boston, and Chicago— where the nation's commerce concentrated. Census takers at the end of the century counted over one million southern-born whites living outside their birth region.

They also counted 335,000 southern-born African Americans living in the North and West in 1900. African Americans had left the South in the nineteenth century for different reasons and in different directions. Emancipation brought freedom of travel and increased out-migration, much of it directed towards northern cities. New York and Philadelphia received thousands of freed people from Virginia and Maryland after the war, and these two cities along with Chicago would remain key destinations for African Americans leaving the South during the Gilded Age. Kansas was also important. In the 1870s black southerners began to move into that state looking for farmland and social freedoms that had become hard to find in the South as Reconstruction came to an end.

The twentieth century changed the volumes and logic of both population movements. Southern out-migration picked up right from the start of the new century, with flows accelerating in the second decade thanks to the job opportunities of World War I. By 1920 southerners living outside their home region numbered more than 2.7 million, in 1930 more than 4 million. Another, even larger surge during World War II raised the total to 7.4 million in 1950, 9.9 million in 1960, 10.8 million in 1970, and 12 million in 1980. That was the peak. As the Sunbelt basked and northern cities rusted, the population of southern expatriates began to decline, dropping to 11.7 million in 1990 and 10.2 million in 2000.

The number of migrants was much larger than these census counts which do not take into account return migration and mortality. In The Southern Diaspora, James Gregory calculates that more than 27 million southerners left their home region over the course of the 20th century. More than 7 million black southerners, nearly 20 million white southerners, more than one million southern-born Latinx southerners, and smaller numbers of Indigenous and Asian-ancestry southerners participated in the diaspora, some leaving the South permanently, others temporarily.

The migration divides into two distinct periods. The first phase started with the initial decade of the century. Migration volumes grew in the teens when at least 1.3 million southerners left home, reached a peak in the 1920s with two million new migrants, then tapered off in the 1930s. A much bigger second wave began with World War II when more than 4 million southerners moved north or west, grew even larger in the 1950s when at least 4.3 million left the South, remained near that level through the 1960s, and then declined in the 1970s and following decades.

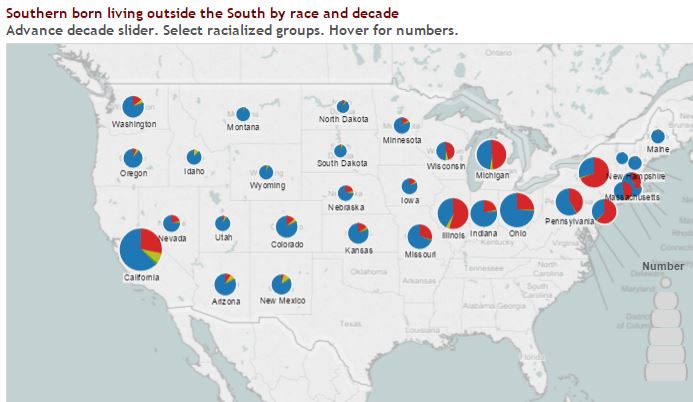

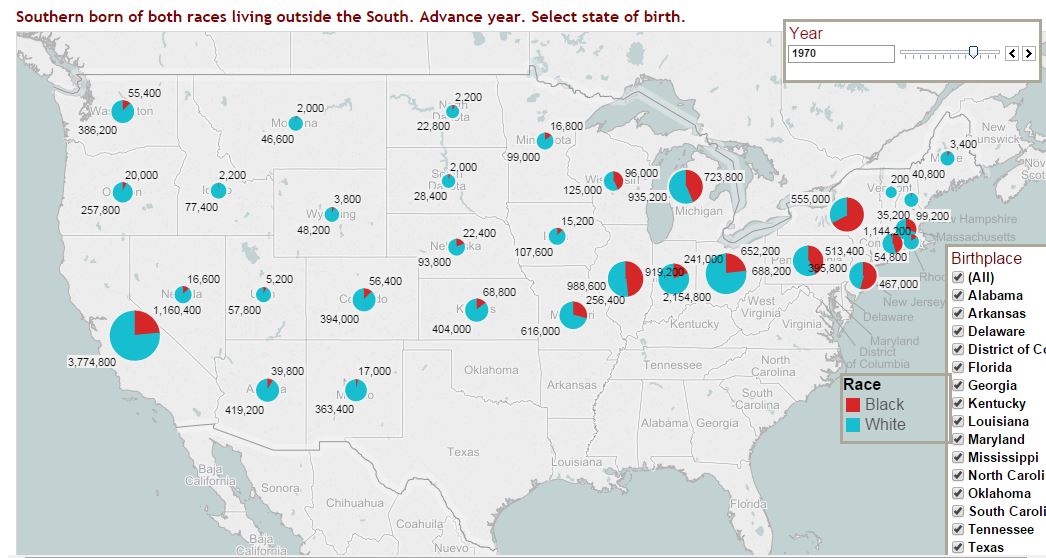

Here are interactive maps and charts that show various dimensions of the great migrations of Whites, Blacks, Latinx, Native Americans, and Asian Americans out of the South. They show decade by decade the number of southerners living in northern and western states. Select a decade and a state of origin and see where people went. Or select a state of residence and see the states of origin. Filter or compare by racial categories. Explore

Here are interactive maps and charts that show various dimensions of the great migrations of Whites, Blacks, Latinx, Native Americans, and Asian Americans out of the South. They show decade by decade the number of southerners living in northern and western states. Select a decade and a state of origin and see where people went. Or select a state of residence and see the states of origin. Filter or compare by racial categories. Explore

Book

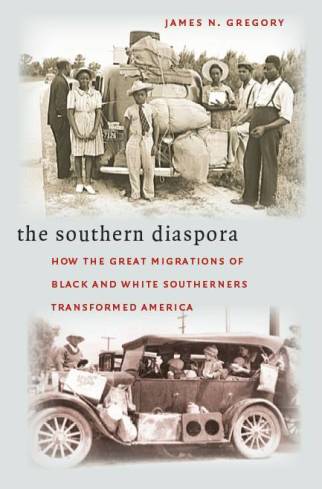

Highlights from The Southern Diaspora: How the Great Migrations of White and Black Southerners Transformed America,by James Gregory (University of North Carolina Press, 2005) winner of the 2006 Phillip Taft award for the best book in Labor History.

Historians usually separate the stories of the Great Migration of black southerners from the Dust Bowl and Appalachian migrations of whites. The Southern Diaspora brings them together to show the connections and differences. Here you will find information about the experiences of migrating southerners of both races. You will also find information on the impact and legacy of the dual migrations.

The Southern Diaspora transformed American religion, spreading Baptist and Pentecostal churches and reinvigorating evangelical Protestantism, both black and white versions. It transformed American popular culture, especially music. The development of Blues, Jazz, Gospel, and R&B and the development of Hillbilly and Country Music all depended on the southern migrants.

The Southern Diaspora enabled the transformations in politics and culture that set up the Civil Rights era. Black southerners in the great cities of the North and West developed institutions and political practice that resulted in momentous changes in the system of race and rights. The Diaspora also helped reshape American conservatism, contributing to new forms of white working-class and suburban white politics, especially since the 1960s. Indeed most of great political realignments of the second half of the twentieth century had something to do with the population movements out of the South.

Essays