Dustbowl Migration

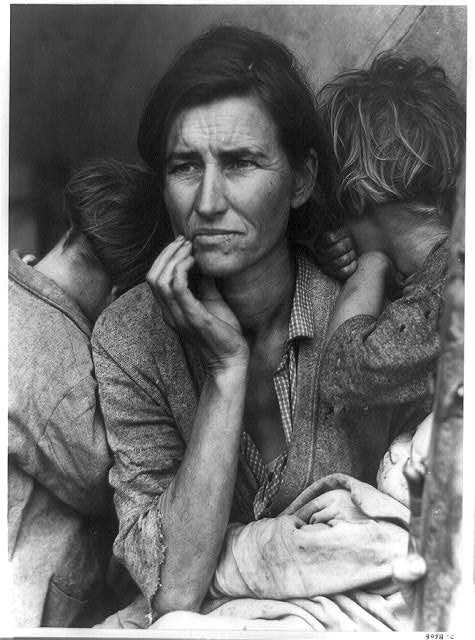

Family arriving in Los Angeles from Oklahoma in 1935. Dorothea Lange photo.

Family arriving in Los Angeles from Oklahoma in 1935. Dorothea Lange photo.

The press called them Dust Bowl refugees, although few came from the area devastated by dust storms. Instead they came from a broad area encompassing four southern plains states: Oklahoma, Texas, Arkansas, and Missouri. More than half a million left the region in the 1930s, mostly heading for California. In a decade when migration rates dropped nationwide, the families leaving the southern plains attracted a great deal of attention. But actually they were part of a migration sequence from that region that had been going on for decades and would continue long after the 1930s.

Southern Diaspora

The westward migration of White folks from Oklahoma and neighboring states can be seen as part of a broader exodus from the South that included the Great Migration of southern Black families and still larger outmigration of southern White families. The Southern Diaspora saw nearly 20 million people leave the economically troubled South in the first seven and half decades of the 20th century. Click here learn more about the Southern Diaspora and explore our interactive maps and charts Below we focus on the 1930s Dust Bowl migration to California.

by James Gregory

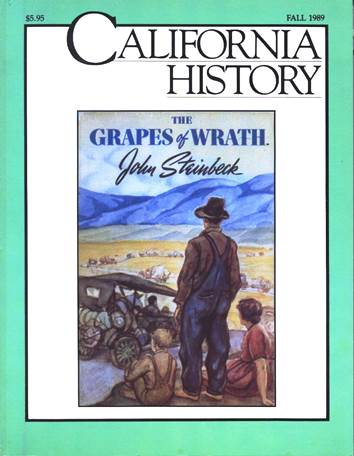

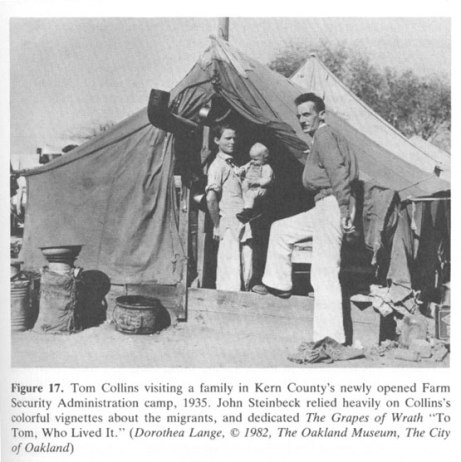

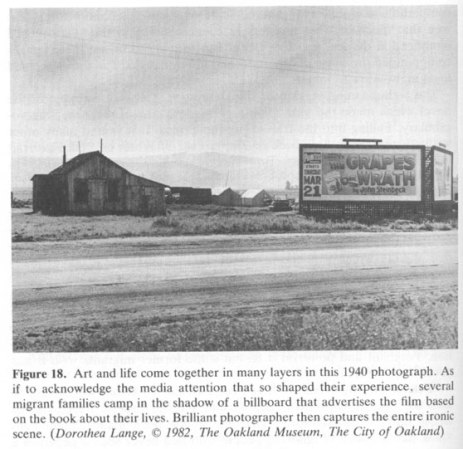

It became one of those rare books that not only records history but makes history. Even as the first copies of The Grapes of Wrath rolled off the presses in the spring of 1939, it was clear that the novel was going to have an extraordinary impact. John Steinbeck's story of a dispossessed Oklahoma farm family struggling to survive among the fields of plenty in California touched the conscience of a nation.

Steinbeck was not the first to write about the Dust Bowl migrants and their plight. For the better part of four years the story had been earning newspaper headlines, especially in California, where by 1939 the public was in the midst of a massive debate over the "Okie crisis." But Steinbeck did something that the journalists, photographers, and politicians could not do: he made sure that the Okies would never be forgotten. The Grapes of Wrath turned the Dust Bowl migrants into one of the enduring symbols of the Great Depression.

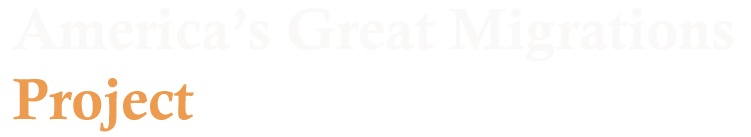

Here are maps showing some dimensions of the 1930s migration. Below that are essays and photos: Map shows the number of migrants from the five southern plains states during the key years 1935-1940

The 1940 Census asked people where they had lived five years earlier. This gives us information about 286,746 people from the southern plains who moved to California in that interval. This was not the start of migration from the region. People had been moving west since the Gold Rush. Numbers escalated in the 1910 and 1920s as cotton growing expanded in California's valleys and as booming Los Angeles attracted migrants from all over.

Map shows where migrants from the five southern plains states settled in 1935-1940

Map shows where migrants from the five southern plains states settled in 1935-1940

The map above disrupts one stereotype. While some of the migrants were farm folk who sought work in the Central Valley, many left towns and cities and headed for Los Angeles and other urban areas.

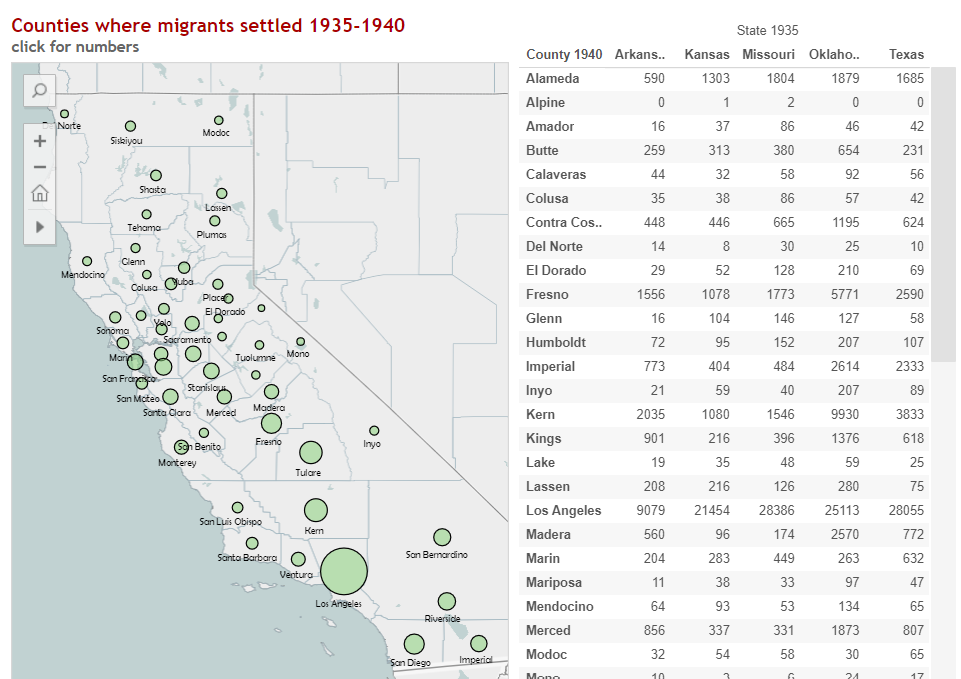

Map shows all migrant to California in 1935-1940

Map shows all migrant to California in 1935-1940

People from the southern plains comprised more than one-third of all migrants to California in the late 1930s, as shown in the map above, and the percentage was much higher in the San Joaquin Valley. This was part of why migrants from Oklahoma and neighboring states attracted so much attention.

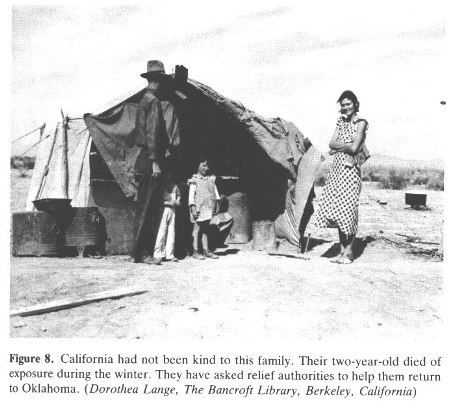

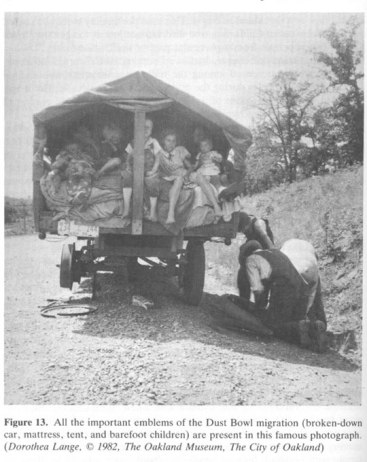

Poverty was the other reason. Scenes of desperation along the highways and in farm labor camps caught the attention of journalists and photographers who coined the term "Dustbowl refugee," mistakenly assuming that people had fled the dramatic dust storms that had ravaged counties in the Oklahoma and Texas panhandles earlier in the decade. John Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath crystalized the image of "Okies and Arkies" struggling to survive in California's Central Valley.

Read more about these issues in two essays:

Updating The Grapes of Wrath:

The Okie Impact on California

This is an edited version of "Dust Bowl Legacies: The Okie Impact on California 1939-1989," California History (Fall 1989)

This is an edited version of "Dust Bowl Legacies: The Okie Impact on California 1939-1989," California History (Fall 1989)

by James Gregory

It became one of those rare books that not only records history but makes history. Even as the first copies of The Grapes of Wrath rolled off the presses in the spring of 1939, it was clear that the novel was going to have an extraordinary impact. John Steinbeck's story of a dispossessed Oklahoma farm family struggling to survive among the fields of plenty in California touched the conscience of a nation.

Steinbeck was not the first to write about the Dust Bowl migrants and their plight. For the better part of four years the story had been earning newspaper headlines, especially in California, where by 1939 the public was in the midst of a massive debate over the "Okie crisis." But Steinbeck did something that the journalists, photographers, and politicians could not do: he made sure that the Okies would never be forgotten. The Grapes of Wrath turned the Dust Bowl migrants into one of the enduring symbols of the Great Depression.

Ever since 1939, Americans of various generations have found in the tragic heroism of the Joad family a metaphor for the nation's depression-era experience. And what has become of the real Dust Bowl migrants, the Oklahomans, Arkansans, Texans, and Missourians who were the models for Steinbeck's book? It is fitting that we update the story. Steinbeck never did. It is too bad, for he would have been quite surprised. The experiences of the Dust Bowl migrants in subsequent decades defied many of the understandings and expectations that governed his 1939 portrait.

The Grapes of Wrath foresaw a difficult future for the Okies and Arkies. Steinbeck was not at all sure that California could or would provide an adequate home, and he thought a great deal depended upon important changes in the structure of California agriculture.

The Dust Bowl Migration:

Poverty Stories, Race Stories

A version of this essay was published as "The Dust Bowl Migration," in Poverty in the United States: An Encyclopedia of History, Politics, and Policy, eds. Gwendolyn Mink and Alice O'Connor (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-Clio, 2004)

A version of this essay was published as "The Dust Bowl Migration," in Poverty in the United States: An Encyclopedia of History, Politics, and Policy, eds. Gwendolyn Mink and Alice O'Connor (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-Clio, 2004)

by James Gregory

Although it was but one episode out of many struggles with poverty during the 1930s, the Dust Bowl migration became something of synecdoche, the single most common image that later generations would use to memorialize the hardships of that decade. The continuing fascination with the Dust Bowl saga also has something to do with the way race and poverty have interacted over the generations since the 1930s. Here is one of the last great stories depicting white Americans as victims of severe poverty and social prejudice. It is a story that many Americans have needed to tell, for many different reasons.

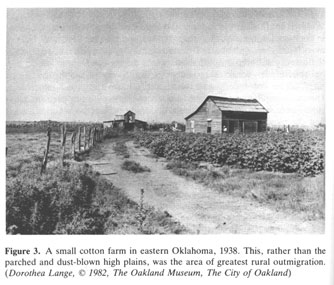

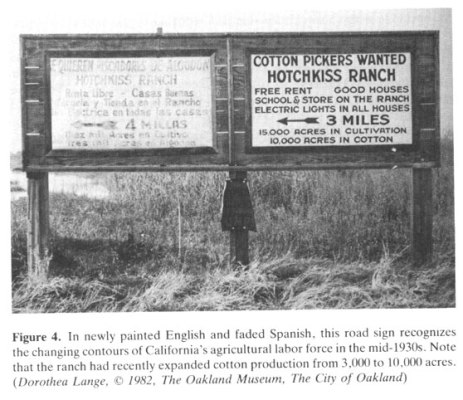

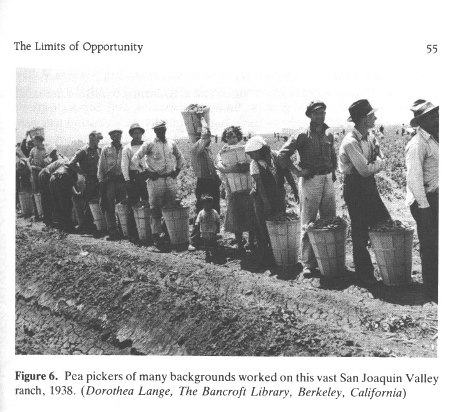

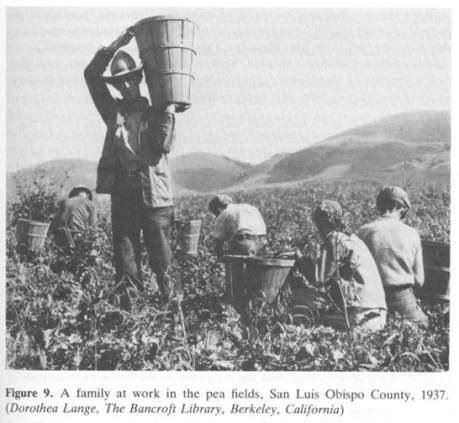

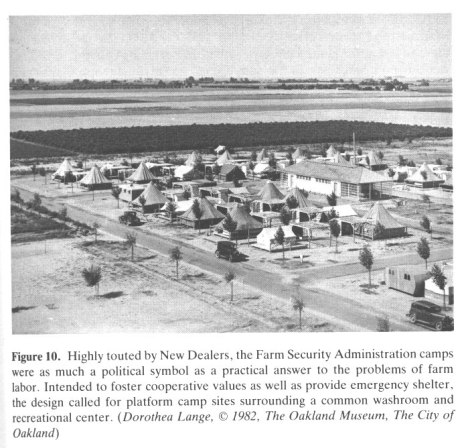

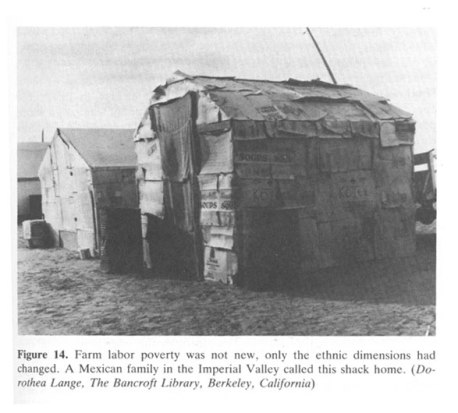

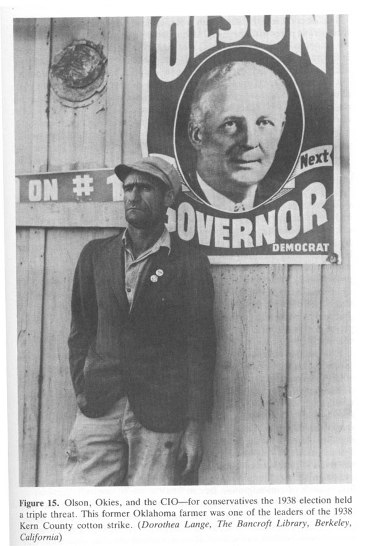

The story begins in the summer of 1935. That is when the economist Paul Taylor realized that something new was happening in California's agricultural areas, particularly the wondrously productive San Joaquin Valley which supplied two dozen different kinds of fruits and vegetables to the nation's grocery stories and the highest quality cotton fiber to its textile mills. The workers who picked those crops had been mostly Mexicans, Filipinos, and single white males before the Depression. Now Taylor, an expert on farm labor issues, noticed more and more whites looking for harvest labor jobs, many of them traveling as families, a lot of them with license plates from Oklahoma, Texas, and Arkansas.

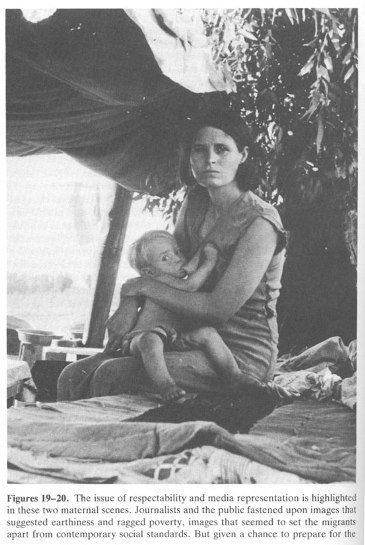

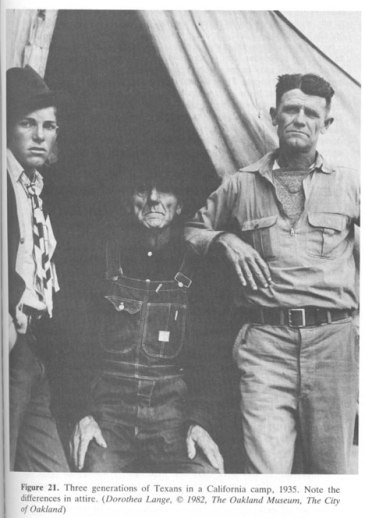

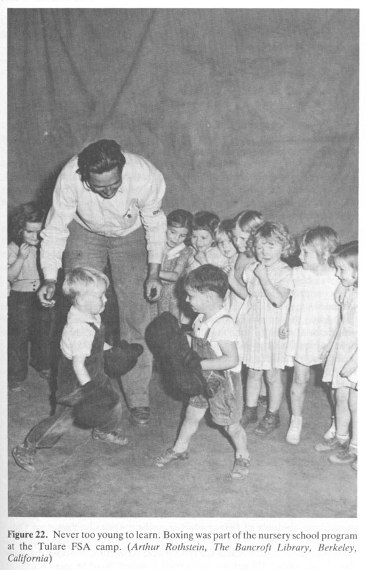

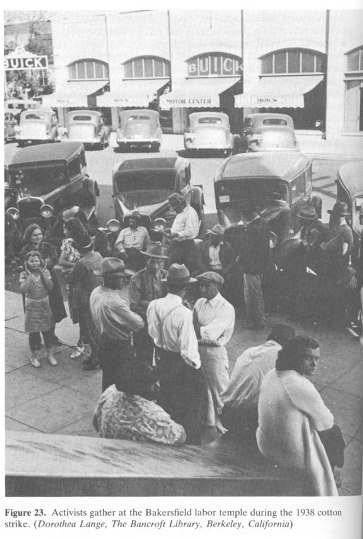

Below is a photo essay from American Exodus James Gregory's prize-winning book

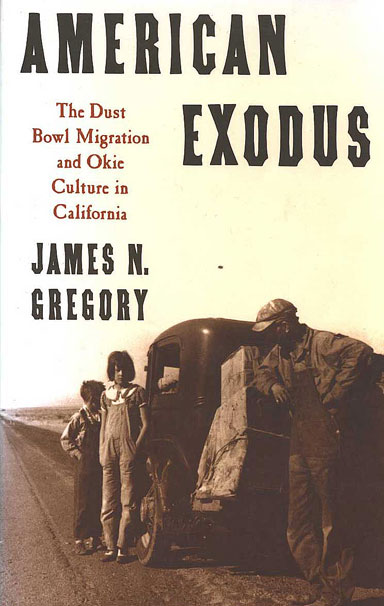

Below is a photo essay from American Exodus James Gregory's prize-winning book From the dust jacket:

"Fifty years ago, John Steinbeck's now

classic novel The Grapes of Wrath captured the epic story of an

Oklahoma farm family driven west to California by dust storms, drought,

and economic hardship. It was a story that generations of Americans have

also come to know through Dorothea Lange's unforgettable photos of

migrant families struggling to make a living in Depression-torn

California. Now in James N. Gregory's path-breaking American Exodus,

there is at last an historical study that moves beyond the fiction

of the 1930s to uncover the full meaning of these events.

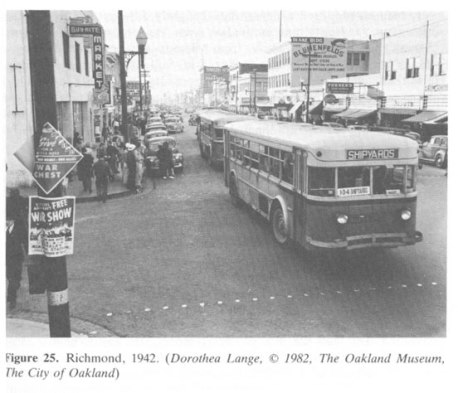

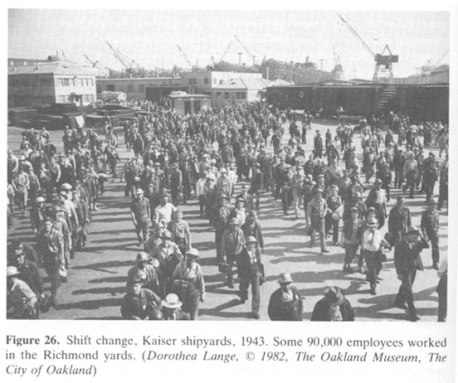

"American Exodus takes us back to the Dust Bowl migration of

the 1930s and the war boom influx of the 1940s to explore the

experiences of the more than one million Oklahomans, Arkansans, Texans,

and Missourians who sought opportunities in California. Gregory reaches

into the migrant's lives to reveal not only their economic trials but

also their impact on California's culture and society. He traces the

development of an "Okie subculture" that over the years has grown into

an essential element in California's cultural landscape.

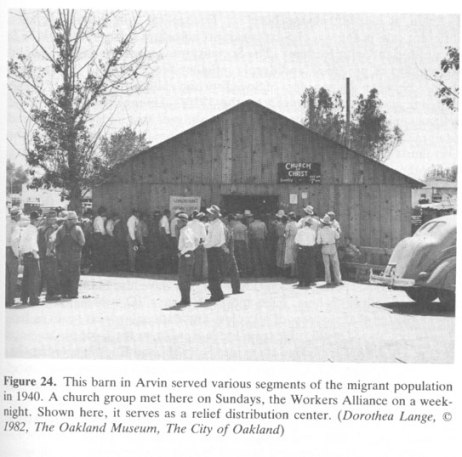

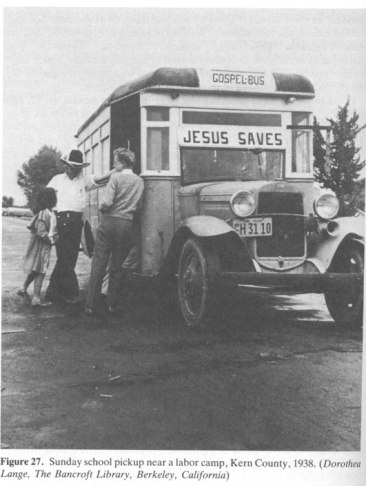

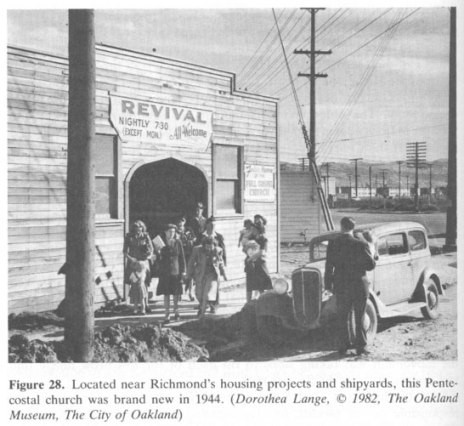

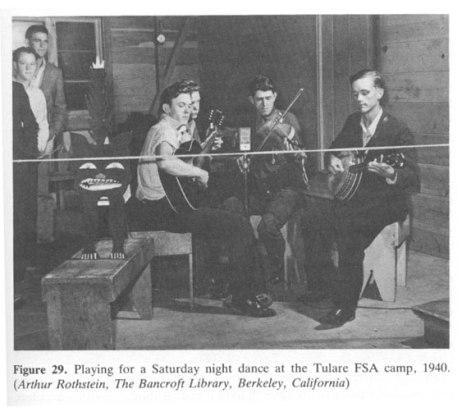

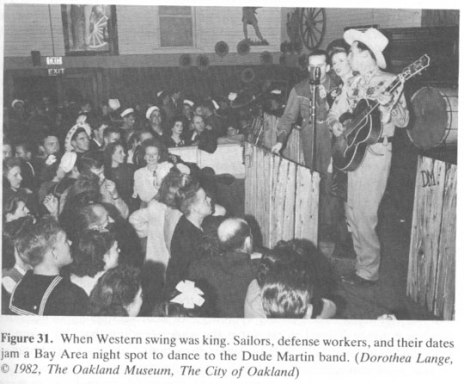

"Gregory vividly depicts how Southwesterners brought with them

on their journey west an allegiance to evangelical Protestantism,

"plain-folk American" values, and a love of country music. These values

gave Okies an expanding cultural presence in their new home. In their

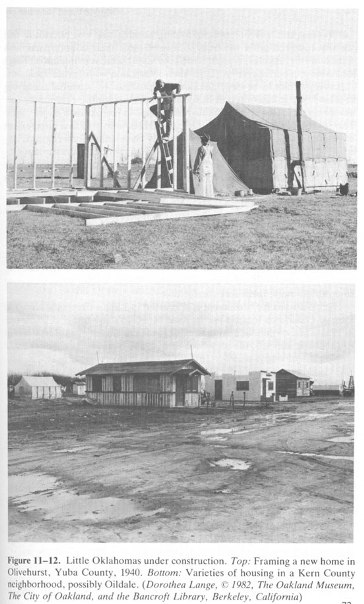

neighborhoods, often called "Little Oklahomas," they created a community

of churches and saloons, of church-goers and good-old-boys, mixing ster-minded

religious thinking with hard-drinking irreverence. Today, Baptist and

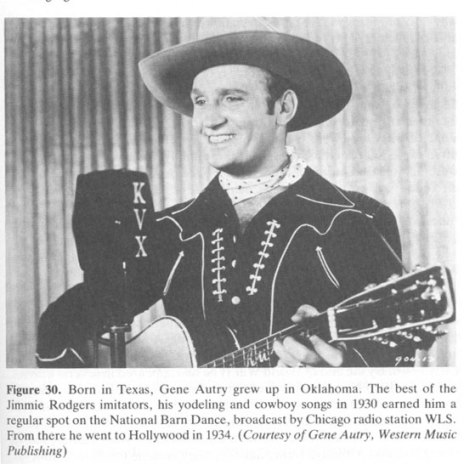

Pentecostal churches abound in this region; and from Gene

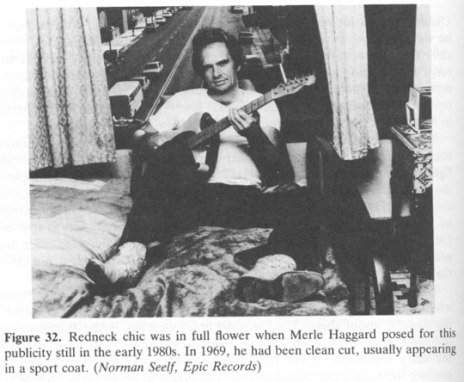

Autry--"Oklahoma's Singing Cowboy"--to Woody Guthrie, Bob Wills, and

Merle Haggard, the special concerns of Southwesterners have long

dominated the country music industry in California. The legacy of the

Dust Bowl migration can also be measured in political terms. throughout

California and especially in the San Joaquin Valley, Okies have

implanted their own brand of populist conservatism."

photo essay

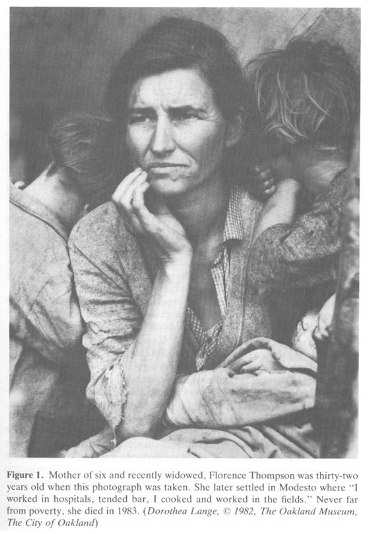

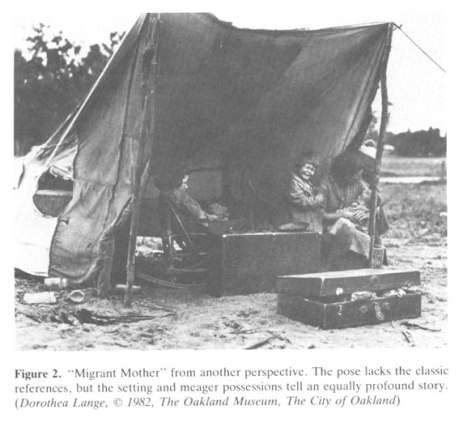

from James N. Gregory, American Exodus: The Dust Bowl Migration and Okie Culture in California

from James N. Gregory, American Exodus: The Dust Bowl Migration and Okie Culture in California

from James N. Gregory, American Exodus: The Dust Bowl Migration and Okie Culture in California

from James N. Gregory, American Exodus: The Dust Bowl Migration and Okie Culture in California

Other online resources

- Listen to the "Voices from the Dust Bowl: The Charles L. Todd and Robert Sonkin Migrant Worker Collection 1940-41" Here you will find songs and interviews recorded in the San Joaquin Valley migrant labor camps.

- Read the oral history interviews in California Odyssey: Dust Bowl Migration Digital Archives. This is a collection of 53 interviews conducted in 1980 and 1981 in Kern County, California.