November 24, 2025

Project Highlight: North Coast and Cascades Network Bat Population Monitoring and White-Nose Syndrome Surveillance

By Kylie Baker

Echoes in the Night: Tracking White-Nose Syndrome and Monitoring Bats Across the Pacific Northwest

In the quiet darkness of Pacific Northwest forests, bats perform a vital ecological service: chowing down. From tiny midges and biting flies that bother humans, to moths that threaten crops, to beetles that affect forest health, bats consume a remarkable diversity of insects. They also serve as an important food source for birds of prey, such as hawks and falcons. Whether predator or prey, bats help keep ecosystems in balance. Yet in recent years, these nocturnal mammals have faced a deadly threat: white-nose syndrome (WNS).

WNS is caused by the fungus Pseudogymnoascus destructans (Pd), to which bats become vulnerable during hibernation. While torpid, bats experience reduced body temperatures and suppressed immune function, which allows the fungus to grow into their tissues, particularly on their wings and muzzles. This fungal invasion disrupts normal physiological cycles, causing bats to arouse more frequently than they should and burn through the fat reserves they need to survive winter. Since its first detection in New York in 2006, WNS has swept across North America, killing millions of bats and devastating populations of several species.

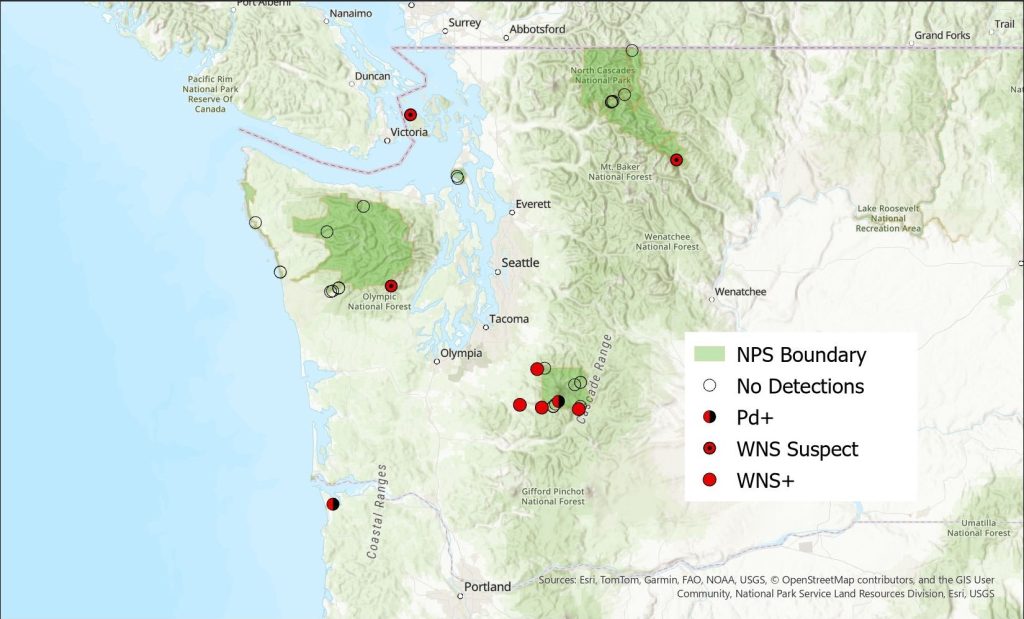

The first signs of Pd in Washington were detected in 2016 near North Bend — the first confirmed case west of the Rockies. The discovery triggered widespread concern among land management agencies and wildlife biologists, prompting a rapid, coordinated interagency response to monitor and manage the disease’s spread throughout the Pacific Northwest. Three National Park Service (NPS) Inventory and Monitoring Networks: North Coast and Cascades, Klamath, and Upper Columbia Basin — covering parks in Washington, Oregon, northern California, and Idaho — joined forces to develop the Pacific West Region WNS Response Plan.

That summer, Mount Rainier National Park hosted an interagency workshop to identify regional monitoring priorities and opportunities to leverage funding, expertise, and support. The NPS WNS-response fund source enabled the agency to secure additional resources through the Pacific Northwest Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit (PNW CESU) — a network that fosters collaboration and shared scientific capacity among federal agencies, universities, nongovernmental conservation organizations, and other partners.

This partnership became the North Coast and Cascades Network (NCCN) Bat Monitoring Project, a cornerstone of WNS surveillance and bat research in the Pacific Northwest. The effort brought together technical experts from diverse backgrounds, including disease ecology, molecular genetics, acoustic monitoring, and bat biology from the NPS, U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), Oregon State University’s (OSU) Quantitative Wildlife Ecology, Conservation, and Environmental Genetics Lab, and the Northwest Bat Hub at OSU–Cascades.

As with many CESU initiatives, the project’s impact extends beyond its primary partners, supported by a broader regional community engaged in bat conservation. The NCCN team works directly with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) and with the North American Bat Monitoring Program (NABat) through coordinated acoustic data collection. The team also communicates periodically with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) to share findings and discuss regional WNS updates, and although not direct collaborators on this specific project, other agencies such as the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) and Bureau of Land Management (BLM) contribute valuable data to statewide NABat monitoring efforts.

Project Origins

The NCCN Bat Monitoring Project began as a proactive surveillance program spearheaded by Tara Chestnut, then an NPS ecologist at Mount Rainier National Park (now with the USFS). Her early work laid the foundation for a coordinated, region-wide approach to tracking bats and the spread of WNS.

By implementing the Pacific West Region WNS Response Plan, Tara mobilized teams to locate bat roosts within NCCN parks, conduct disease surveillance, and collect acoustic data — recordings of bat echolocation calls used to identify species and track activity. Early field crews were funded through NPS partnerships with Historically Black Colleges and Universities, AmeriCorps Scientists-in-Parks, and the Mosaics in Science Program through the nonprofit Environment for the Americas, offering students hands-on experience in wildlife research.

An essential part of the WNS Response Plan was clear and quick communication among state and federal partners. This framework — focused on early detection and rapid response — mirrors approaches used in managing emerging diseases and invasive species.

Today, Rebecca McCaffery and Michael Hansen, wildlife biologists with the USGS Forest and Rangeland Ecosystem Science Center (FRESC), lead the project. Their team works closely with park and regional partners to understand how bat populations are responding to WNS and to develop long-term monitoring strategies that guide conservation actions.

When WNS was first detected in Washington, most of the region’s parks had not systematically studied bats since the 1990s, when tools for species detection were far less advanced. The first step was to identify colonies within each park — in bat boxes, buildings, or bridges — where bat monitoring and disease surveillance could occur. Using the USGS NABat framework, FRESC designed a study deploying acoustic detectors across NCCN parks to determine which bat species were present, where they were most active, and how activity changed seasonally. Data collected in 2019 and 2020 established a crucial baseline against which to measure changes in bat activity, which may be attributed to the spread and impacts of WNS in subsequent years.

Monitoring in Motion

The NCCN project established strong partnerships with NABat and OSU–Cascades’ Northwest Bat Hub, initially led by Roger Rodriguez and now by Beth Ward, to develop a regionally coordinated acoustic monitoring framework that extends beyond NCCN park boundaries. The team deployed acoustic detectors within NABat’s nationwide grid system in Washington and Oregon, while spring disease surveillance — tracking fungal prevalence in bats and their roosts — has been conducted by NPS (early in the project) and now by USGS–FRESC. The Northwest Bat Hub supports the broader state-level NABat acoustic framework, while USGS–FRESC maintains the NCCN’s year-round acoustic monitoring network, providing critical data on seasonal patterns and long-term trends in bat activity.

Collaborations with Taal Levi and Jenny Urbina of OSU’s Quantitative Wildlife Ecology, Conservation, and Environmental Genetics Lab expanded the project’s scope to include laboratory studies — from analyzing DNA degradation rates to understanding Pd growth on different substrates and under various environmental conditions. Their research also explored improved decontamination methods to prevent spreading the pathogen between sites, leading to updates in the USFWS National WNS Decontamination Protocols.

Early in the project, a major challenge was simply knowing where and when different bat species occurred in the Pacific Northwest. Acoustic monitoring helped fill this gap. As part of the project’s baseline work, USGS–FRESC designed and implemented a study in 2019–2020 to monitor bats along elevational and precipitation gradients in Washington’s three large national parks: Olympic National Park, Mount Rainier National Park, and North Cascades National Park. This data — collected largely before WNS became widespread in the region — provides an essential reference point for detecting future changes in bat activity as the disease advances. Today, USGS–FRESC maintains a smaller network of year-round acoustic detectors across NCCN parks to track seasonal patterns and to build the long-term dataset needed to identify potential shifts linked to WNS.

Today, the project employs a suite of complementary methods: acoustic detectors, emergence counts at roosts, telemetry studies, and genetic and disease surveillance. The Northwest Bat Hub manually vets and analyzes thousands of hours of bat calls collected each season. These datasets reveal species presence, seasonal patterns, and subtle shifts in community composition that may signal WNS-related declines. The results also help identify the most productive monitoring sites to capture a diversity of habitats and conditions.

Understanding Disease Dynamics

White-nose syndrome has devastated bat populations in the eastern United States, where large cave systems host dense congregations of hibernating bats — ideal conditions for the fungus to spread rapidly. In contrast, while the Pacific Northwest also has an extensive network of lava tubes and other caves, most bats in this region tend to overwinter in smaller, more dispersed groups within caves, talus slopes, trees, or under bridges. This dispersed behavior may be slowing the pace of the disease’s spread across the region.

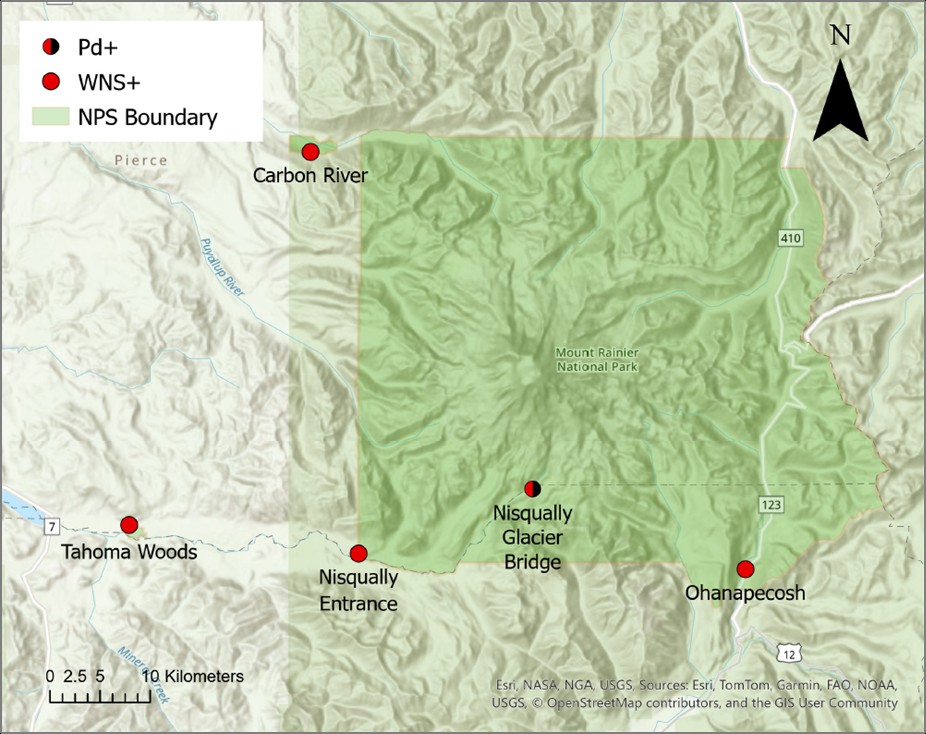

Since the first detection at Mount Rainier in 2017, WNS has expanded across nearly every national park in Washington. Yet its progression has been markedly slower than the rapid wave seen in the East. This pattern offers researchers valuable insight into how local ecology and behavior influence disease transmission.

Because most bats in the Northwest do not hibernate in large, easily monitored colonies, much of the disease’s impact occurs “off-stage.” Acoustic and disease surveillance data thus provide the best window into population trends before visible die-offs occur. With nearly a decade of acoustic data now accumulated, McCaffery and Hansen’s team is beginning to link fluctuations in bat activity to the presence of Pd. Some sites show fungal detections that appear, disappear, and later reemerge — suggesting complex dynamics of exposure, environmental persistence, and possible recovery.

A key next step is integrating disease and acoustic data streams. Large-scale acoustic datasets from NABat currently exist separately from site-specific disease testing results. Connecting these will help scientists better analyze population health and disease outcomes across the landscape.

Innovation Through Collaboration

As WNS continues to spread, the NCCN Bat Monitoring Project remains adaptive and forward-looking. The team is exploring new directions in genetic testing, pathogen detection, and even vaccine-based interventions. A proposed pilot study aims to test the feasibility of vaccinating bats at select colonies within national parks — a promising development following early trials that showed reduced infection intensity and improved survival.

The ability to pursue such cutting-edge work stems directly from the project’s collaborative framework, bringing together experts from a diversity of fields. Through the PNW CESU, researchers can leverage university expertise, pilot new techniques, and pursue questions that might otherwise fall outside agency budgets or missions.

For example, Urbina’s work refined laboratory methods for detecting Pd on bats and environmental surfaces, contributing to updates in national decontamination protocols. Preliminary laboratory findings also indicate that Pd — often described as a “cold-loving” fungus — may survive and later regrow from wood in Pd-positive bat boxes exposed to temperatures as high as 44°C (111°F). While not yet peer reviewed, this line of research highlights how CESU-supported collaborations accelerate discovery by combining agency field expertise, university analysis, and laboratory innovation.

A Model for the Future

Through years of fieldwork, laboratory research, and interagency coordination, the NCCN WNS project has become a model for wildlife disease surveillance and cross-boundary conservation. Combating emerging diseases like WNS often feels like a race against time, but the response has united scientists, managers, students, and volunteers across institutions.

Each partnership — from national programs to local field crews — contributes a crucial piece of knowledge toward a shared goal: protecting the Northwest’s bats and the ecosystems that depend on them. What began as a localized response to an emerging threat has evolved into a lasting framework for collaboration, resilience, and hope in the face of a devastating wildlife disease.