The Seattle branch of the Black Panther Party was the first group established outside of the state of California. Its existence is an illustration of how peripheral branches of an organization would both adhere and diverge from the program established by the national headquarters. The evidence suggests that the Seattle Panthers often respected the Party’s national leadership and worked hard to follow the national agenda. However, to say that the Seattle BPP was completely dependent on Oakland’s guidance and dictates would be an error. The behavior of the Seattle BPP was also influenced by its local leadership and local circumstances in the city of Seattle.

Two and a half years before the start of the Seattle chapter, the Black Panther Party was born in Oakland, California. Huey Newton and Bobby Seale started the organization on October 15, 1966, and it was originally called the Black Panther Party for Self Defense. Its goal was to prevent police brutality as well as establish a new social, political, and economic order, heavily based upon Marxist doctrine, to improve the Black community. These goals were spelled out in the Panthers’ Ten-Point Program. It contained ten demands for Black power, independence, access, protection, and rights. In effect, it was a demand for equal participation for Blacks in every aspect of American society.1

Aaron Dixon notes that the Ten Point Program was the framework for BPP chapters across the nation. All activities were to fall within the realm of that mission and weekly reports were sent to Oakland to inform personnel at the headquarters how the Seattle Panthers were adhering to that program. Dixon adds some discretion was allowed.2 But for the most part the Seattle Panthers did not diverge far from the goals and expectations of the Oakland branch. This was due in part to the Seattle leaderships’ belief in the worth of the BPP program. Members of the Seattle Panthers even helped create some of these strategies. Elmer Dixon recalled:

There was a close connection [between Seattle and Oakland]. We often would travel the I-5 Corridor, it was our subway to the Bay Area and we’d often go there two or three times a month, if not more often, just to sit down and talk shop with Bobby. [We’d] talk about strategy and what we’re going to do [and] what direction we were heading.3

The Panther agenda involved constant training. Members were expected to become experts in weapons usage and they were also required to attend political education classes. Upon being accepted into the party, each member had to participate in a six-week training program that included reading a list of twenty five books. One of the Dixons’ tasks was to organize and run these classes. Aaron Dixon stated that they were “used to make sure that everybody understood the ideology of the party and that we were on the same page in terms of the theory and the rules of the party.” It was the goal of the party, Dixon said, to have informed and articulate members.4

Recruiting members was one of the Party’s most important tasks early on, and one of the target groups was Huey Newton’s notion of the lumpen. Newton had incorporated significant portions of Marxist theory into the BPP program. Marx had discussed the existence of the lumpen proletariat, which he defined as the lowest order of society, the criminals, prostitutes, and malcontents of the streets.5 Marx eschewed their participation in any socialist movements due to what he believed was the lumpen’s inability to take direction. Newton understood the lumpen in a different light by applying a more liberal definition to the group. He believed that the extremely poor who tried to earn a living wage but could not because the shortcomings of capitalism were also part of the lumpen. Newton believed that it would be from this social stratum that the BPP-led revolution would find its most dedicated followers.6

Aaron Dixon guesses that early on some 300 hundred applications were made to the Seattle BPP. Among these potential members were a large number of Seattle’s “lumpen.” He stated that many who joined the BPP were friends of his and were good organizers as well as serious and devoted members. However, the lumpen also introduced a criminal element to the party that was detrimental to the organization. “A lot of people couldn’t change old behaviors and even though we read and studied, we still didn’t have anything to address a lot of the negative elements…” Dixon added that one of the tenets of the party as listed in the Ten Point Program was to never steal property from the masses.7 Yet, some BPP members still ended up committing crimes such as robbery, vandalism, and assault. These activities tainted the reputation of the entire organization and were fodder for critics who saw such behavior as evidence that the Party was more of a street gang than a civil rights organization.8

Of course, there were applicants from outside the lumpen who sought membership in the Party. One such person was Leon Valentine Hobbs. Hobbs was raised in east New York City. He states, “I grew up with morals… Our parents were very conservative. We were taught to respect authority… We knew right from wrong. Most of [my friends] had mothers and fathers…My mother didn’t even work because my father was in the navy and made a good salary.” Hobbs said that living in a northern city and coming from a “good” family did not shield him from the affects of racism. He remembered hearing of Blacks being killed in New Jersey. His parents tried to dissuade their children from associating with white people. “We knew our history and it’s like stay in your place. My great grandfather was killed in Macon, Georgia. [We were] watching our leaders getting wiped out…getting shot down in the streets…[As] we grew up that is what we saw.”9

Hobbs’ most striking experience with racism occurred while he was a young man serving in the army. At Ft. Dix, in New Jersey, he was called a “nigger” and was then locked up when he took offense. He was likewise angered by a stint at a military post in Georgia. “We could not even go off the [post] because they were still killing and lynching black soldiers if they were caught off base. They still had separate bathrooms and water fountains…in Georgia…And here we are getting ready to go [to Vietnam] to fight. So what am I fighting for?”10 Hobbs’ experiences with racism had steered him toward the separatist ideas of Malcolm X. For Hobbs, white America had given little indication that it was concerned with black rights. He believed strongly that integration was anathema to black welfare and progress.11

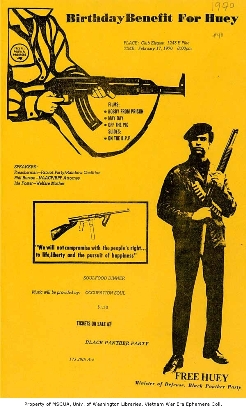

Hobbs came to Seattle in 1969 when he was hired to work in the Model Cities program. He first met Aaron and Elmer Dixon while in the midst of a contentious discussion concerning the BPP’s use of allies. Hobbs was attending a birthday celebration for Huey Newton being held at a club in Seattle. While there he had a run-in with a White Panther leader.12 Hobbs recalled, “I was asking [the White Panther] questions. What are you going to do when the white people come down, when things get thick? You are going to thin out, right?” At that point, Hobbs said Aaron Dixon approached him. “Aaron…tried to explain to me about the coalition. I said, ‘Man, I don’t care about no coalition…’ I wasn’t in the Party then, [but] I was for Black people. Aaron said we’re for Black people too, but we need to care about all oppressed people in the country.”13

Aaron Dixon’s argument was in line with Newton’s belief in the creation of an alliance of disaffected people. Newton, and others within the Party, concluded that for the BPP to succeed, especially politically, a large membership was necessary. Newton believed that there were numerous segments of the America’s disaffected population, who might be willing to unite with the Panthers and their agenda. These groups included the Peace and Freedom Party, the White Panthers, women’s and gay groups, the Brown Berets (Chicano), and the Young Lords (Puerto Ricans).14 At the same time the Panthers were adamant critics of Black cultural nationalism espoused by groups such as United Slaves (US).15

Hobbs said that he continued to talk to the Dixons and became interested in the Party. He recalled that he was “intrigued with the Ten Point Program… As human beings we have a right to housing, clothing, shelter, medical care and anything everybody else is supposed to have.” Hobbs knew that if he wanted to join, he had to compromise his anti-integration beliefs. He said other Panthers shared his point of view, but he adds, “Everybody finally realized that we were all going in the same direction and we should not let…certain ideas that you have take you off the course. I understood that we needed coalitions because we are in a predominantly white country…[Still] I was not very trusting of white people.”16

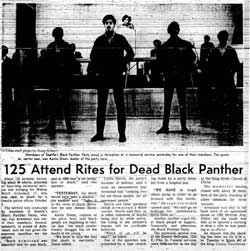

Hobbes’ willingness to temper his personal inclinations in order to fit the requisites of the BPP represents some of the decisions that members had to make regarding the alignment of personal and Party ideals. These same decisions had to be made at the institutional level. Seattle was not Oakland so not all of the dictates emanating from headquarters were transferable. Thus, there were incidents large and small where the local branch took its own counsel and acted accordingly. One involved a visit by the BPP to Seattle’s Rainier Beach High School. It is illustrative of the role that the Seattle Panthers came to find themselves as having within the community. It also exemplifies a level of autonomy that a local chapter could have. Aaron Dixon stated that after the Seattle BPP had first opened its office it received a large number of telephone calls from people within the Central Area who would ask the Panthers to attend to various problems such as landlord issues, domestic violence, and numerous other problems that arose in a typical community. Dixon said that he and his fellow Panthers became overwhelmed by these requests so he eventually spoke to Bobby Seale about it. Seale said the BPP was not the police and therefore should not be responding to those types of calls. Dixon said the Panthers therefore began to ignore requests. This moratorium did not last. Dixon said the office started to receive calls from a particular woman whose son was being accosted by white students at Rainier Beach High School. During her first call she was told that there was nothing that the Panthers could do. But she proceeded to call day after day. Then one day she called and it was obvious she was in tears. Around the same time three other mothers called and voiced the same concerns. Dixon said there were over a dozen Panthers in the office when this particular set of calls came in and they decided to take action. So they grabbed their guns, piled into several cars, and drove to Rainier Beach. When they got there the Panthers walked into the school with their weapons and found the principal. Dixon said they told him why they were there and that he needed to start protecting students. Dixon said he assured the principal that if the Panthers received more calls regarding the problem, they would return. Before long the police arrived but the Panthers left without incident.17

The visit by the armed Panthers provoked an outcry. One newspaper accused the Panthers of responding to “rumors.”18 Seattle’s Mayor, J.D. Braman, charged the Panthers with vigilantism by “taking the law into their own hands.” The mayor also painted the Panthers as a threat to stability. “It has boiled down to about one or two percent of our black population causing all our racial troubles. This cannot be tolerated. I am very proud of the vast majority of our black population for their cooperative attitudes. But people who seek trouble are in for trouble.”19 Numerous parents of predominantly white Rainier Beach students planned a boycott of the school to protest the BPP’s appearance. One parent stated, “Something should be done to prevent the Black Panthers from walking into school grounds carrying rifles.”20 Dixon said, he also received comments from Oakland ’s Panthers. “When [BPP] headquarters found out about this [incident], they thought we were pretty wild and crazy.” Despite these reactions, Dixon said the Party’s action was effective. They never received another call from the mother of the victim.21

Besides illustrating the Seattle BPP’s occasional autonomy, the Rainier Beach incident was also emblematic of the Panthers’ use of the gun as a practical and symbolic means to realize their goals. From the very beginning of the Party’s existence in Oakland, the gun was used as a tool for self-defense as well as an iconic representation of the Panthers’ commitment to their program. This symbolism overshadowed virtually every other characteristic the Party had.

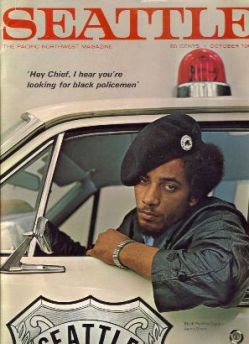

The use of the gun was born of necessity. One of the first priorities of the Oakland BPP was to put a halt to police violence in the Black sections of Oakland. To do this, Black Panthers would patrol the streets of Oakland carrying a firearm and a law book. Their strategy was to appear at incidents that involved blacks and police to make sure that they followed the letter of the law. Besides openly carrying guns, the Panthers also dressed in black leather jackets and berets. They held weapons training sessions and drilled in public. The group purposely projected an armed, militant persona, and the media eagerly portrayed them in that manner. One observer noted, “These guys weren’t like the Elijah Muhammad guys, who would sell you a two-week-old paper and laugh behind your back. They weren’t like…Martin Luther King or any of the others. These guys were scary.”22 The BPP’s portrayal as armed militants grew out of its rhetoric, platform, and armed confrontations between Panthers and the police. For example, in 1967, Newton was involved in a shootout with Oakland police, in which he was wounded and one officer died. Then, of course, there was the shootout with Oakland police that resulted in the death of Bobby Hutton. In reality, the Panther’s use of the gun represented but one aspect of the Party. The move away from that symbol, in 1969, indicates an evolution within the Party. This change in policy was not welcomed by all of the BPP chapters in the country, but it was generally embraced in Seattle.

The Dixons recognize that the armed persona of the BPP was controversial and did present problems for the Party. Still, for both men there was value in its application. Aaron Dixon said, “The virtue was that people knew that we were really serious…and we were ready to defend ourselves and use our weapons if we had to.”23 Elmer Dixon adds that the gun indicated that:

We [black Americans] were no longer going to be hosed by police, bitten by police dogs, bombed in our churches… We were a symbol. The impression we wanted to give was that we were not cowards. We were men…We were not going to beg for our rights…We were trying to forge change by whatever means we could.24

Leon Hobbs echoed the Dixons in stating, “…Our lives were in danger and…we had a human right to defend ourselves against bodily harm, as opposed to when Martin Luther King…would demonstrate and people would hit him…and sick dogs on them. We weren’t going that way.”25

Aaron Dixon concedes that despite the power of the gun’s symbolism, it did have its obviously negative aspects. Both he and Elmer were arrested numerous times as the police constantly were watching them and stopping them for minor traffic violations.26 Elmer Dixon adds that the situation also cast an aspect of fatalism upon the Panther members. He said that when he joined the Party at age seventeen,

…I had two bodyguards who were with me most times and I had to carry a gun with me every place I went…I knew I was a target and I could be killed at any moment…I had police hold guns to my head and people call my mother in the middle of the night and say, ‘We’re going to kill that nigger son of yours.’ I don’t think any of us thought we would live past twenty-five…27

Because of the negative attention armed militancy brought to the Party, Aaron Dixon said that the BPP realized that such an image had a shelf life. “In a very short period of time it became somewhat clear that persona was doing us more harm than good. This led the party to change tactics.” He said the party put away its uniforms and guns and tried to give the appearance of a more “mainstream” organization. Dixon believes this was the right move because it fostered relations within the community. People came to see that the Party was not focused on violence but on confronting prejudice.28

The transformation of the Black Panther Party away from the symbolism of the gun to that of what Dixon called a “mainstream” organization took place around 1969. While Huey Newton was in prison for his 1967 shootout with police he called for a new strategy based upon his theory of Intercommunialism.29 Part of this strategy included the establishment of survival programs which were designed to help the Black community gain the confidence that it could take care of itself, as well as help people within the community obtain their basic needs. Once basic needs were addressed the community could concentrate on more abstract concerns like political theory.30

The Seattle BPP was supportive of the idea of survival programs and displayed both its unity with the Oakland BPP and its independence by actively developing and creating these programs in the Central Area of the city. One immediate consequence in this shift in emphasis was a schism that occurred among the Panther Party at both the national and local levels. In Oakland, Eldridge Cleaver believed that escalating rather than minimizing the Party’s armed militancy was the more appropriate path, and thus broke with Newton and Seale. This schism was to have violent ramifications. A less contentious split took place in Seattle. The Dixons and several of their fellow members, including Leon Hobbs, decided that the vision of Newton and Seale made sense. But, numerous members of the Seattle branch of the BPP were unwilling or unable to jettison the use of the gun from their day-to-day activities so they were expelled from the Party.

Despite the split, Elmer Dixon believes this change in focus was for the better. “There’s no way we could win an armed revolt, so it wasn’t about having an armed revolt it was about having a mental revolt…so that we changed the mentality of the people in the community where they would in fact stand up for their rights and take control…within their community.”31 Aaron Dixon believed that the survival programs were an affective alternative because they not only benefited the community, but they helped soften the image of the BPP, which gave the Party more community support. According to Aaron Dixon, the survival programs were something that the government should have been doing all along. “…We were exposing the contradictions in this country.”32

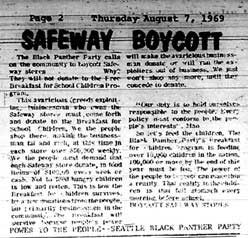

The Seattle survival programs were designed to provide marginalized members of Central Area with basic needs for survival. But though the Party phased out its open display of firearms, it still maintained a high degree of militancy. A case in point was the Seattle Party’s attempt to procure donations for their breakfast program. Elmer Dixon recalled challenging Central Area Safeway grocery stores to become more active in giving back to the community. He said that the Seattle Panthers had concluded that Safeway was profiting handsomely due to the patronage of Central Area customers. In return the company should therefore donate eggs and sausage for children’s breakfasts. In July of 1969, Elmer Dixon presented a letter requesting $100 each week for the breakfast programs. The letter added that if the stores did not comply, the Party would raise the request by $25 each week.33 The stores rebuffed the demand so the Party set up pickets and attempted to institute boycotts.34 Safeway management reported that after the BPP request was denied, Aaron Dixon stood outside the stores with a megaphone, chastising the company and making threats. Also, some vandalism was incurred at the stores after the BPP request was denied, though there was no official link made between the BPP and the damage.35

One of the most significant and groundbreaking survival programs created by the Seattle BPP was the establishment of a Central Area medical clinic. The responsibility for this program was given to Leon Hobbs. Hobbs admitted that he had no experience in such an endeavor before he got started.

I was getting arrested a lot and someone said we have got to direct this guy’s energy in a positive direction…Not that what I was doing was not positive, but there was a lot of confrontation with the police…So Aaron and the Central Committee said they wanted a medical clinic, [and] I was given the task, to organize it.36

One of the first concerns was gathering funding and supplies. Since the BPP did not allow itself to accept any federal monies, all financial resources had to come from private donors. Hobbs said he did a lot of asking and his requests bore fruit. Hobbs believes the amount of the donations served to show the level of community support that the BPP was able to procure. Aside from contributions from groups and individuals within Seattle’s medical community and private sectors, he was also able to receive money from entertainers Jimi Hendrix, James Brown, Greg Morrison, and Buddy Miles. Hobbs also adds that funding, material, time, and expertise donations came from white as well as black sources. He explains that the clinic started small, beginning with well-baby checkups a couple of times each week, and soon added adult care. According to Hobbs, one of the most important contributions of the clinic was the establishment of a sickle cell anemia testing and genetic counseling program. Bobby Seale stated that the Seattle sickle cell testing program was the most affective of all of the BPP’s sickle cell programs in the nation.37 The clinic is still in existence in the Central Area and today it is known as the Carolyn Downs Medical Center.38

With the creation of the survival programs in Seattle, it could be argued that the Dixons had not really diverged from the methodology of Larry Gossett and the BSU after all. As previously stated, it became clear in the minds of Panther members in both Oakland and Seattle that the public display of firearms could be detrimental to the organization’s ultimate goal of a political and economic presence in American society. So alterations to the Party’s public persona were made. The guns were not discarded, but they were tucked away from the public’s view. However, public perceptions of the Panthers did not change as quickly as their methodology did. As a consequence there remained calls for the destroying the Panthers at the national and local levels.

Continue Part 3: The Panthers and the Politicians

(c) Kurt Schaefer 2005

1 “The Ten-Point Program @ http://www.marxists.org/history/usa/workers/black-panthers/1966/10/15.htm

2 Aaron Dixon Interview.

3 Elmer Dixon Interview.

4 Aaron Dixon Interview.

5 Karl Marx, The Communist Manifesto, edited by Frederic L Bender, New York: WW Norton and Co., 1988, 65.

6 For a more in-depth discussion on the lumpen see: Chris Booker, “Lumpenization: A Critical Error of the Black Pantehr Party,” In The Black Party Reconsidered, edited by Charles E. Jones, 337-362. Baltimore: Black Classic Press, 1998, 341, 345, and Jeffrey O.G. Ogbar, Black Power: Radical Politics and African American Identity, 95-99.

7 See: “Rules of the Black Panther Party”, rule number #8: “No party member will commit any crimes against other party members or black people at all, and cannot steal or take from the people, not even a needle or a piece of thread.” @ http://www.marxists.org/history/usa/workers/black-panthers /unknown-date/party-rules.htm.

8 Aaron Dixon Interview.

9 Leon Valentine Hobbs, Interviewed by Kurt Kim Schaefer, February 25, 2005, Seattle, WA.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 The White Panthers was a radical group started by Jon Sinclair in Detroit. In 1968 Sinclair issued the “White Panther Party 10-Point Program” that was somewhat analogous to the Black Panthers program. Its first point in fact called for support of the Black Panthers’ 10-Point Program. The WPP unlike the BPP mixed attributes of the drug and music culture into its agenda. See: Doug Rossnow, “The White Panthers’ ‘total assult on the culture,’” in Peter Braunstein and Michael William Doyle, Imagine Nation: The American Counterculture of the 1960s and ‘70s, New York: Routledge, 2002.

13 LVH Interview.

14 Charles E. Jones and Judson L Jefferies, “’Don’t Believe the Hype’: Debunking the Panther Mythology,” In The Black Panther Party Reconsidered, edited by Charles E. Jones, 25-55, Baltimore: Black Classic Press, 1998, 32.

15 This disagreement was to lead to violent confrontation with the US and the BPP. United Slaves (US) was led by Maulana Karenga. US was based in Los Angeles, and in 1968 the BPP opened an office in that city. US believed in Black cultural nationalism, the idea that a return to African culture would contribute to the realization of Black civil rights. US had a militant wing known as the Simba Wachuka (Young Lions). And US was protective of its LA “turf.” When the BPP appeared in L.A. a confrontation between the two groups occurred on January 17, 1969. A BSU meeting was being held at UCLA to discuss the hiring of a new director for the school’s Black Studies program. Some BPP and US members were students at the school and they began to argue with each other. Guns were drawn and two BPP members, John Huggins and Alprentice “Bunchy” Carter, were killed. See: Floyd Hayes and Francis A. Kiene, III, “All Power to the People”: The Political Thought of Huey P. Newton and the Black Panther Party,” In The Black Panther Party Reconsidered, edited by Charles E. Jones, 156-176, Baltimore: Black Classic Press, 1998, 168-169.

16 Leon Valentine Hobbs Interview.

17 Aaron Dixon Interview.

18 “Armed Panthers Appear at School,” Seattle Times, September 6, 1968, 1.

19 “Mayor Warns Black Panthers,” Seattle Times, September 13, 1968, 1.

20 “Rainier Beach Parents Plan Boycott of School Tomorrow,” Seattle Times, September 8, 1968, 19.

21 Aaron Dixon Interview.

22 Hugh Pearson, The Shadow of the Panther: Huey Newton and the Price of Black Power in America, Menlo Park, CA: Addison-Wesley, 1994, 116.

23 Aaron Dixon Interview.

24 Judith Blake, “Panthers’ Progress,” Seattle Times, October 24, 1986, E-6.

25 Leon Valentine Hobbs Interview.

26 Blake, E-6.

27 Elmer Dixon Interview. In fact two Seattle Panthers were killed due to confrontations with the police: Sydney Miller who died while involved in a robbery and Welton Armstead who was shot while pointing a rifle at a police officer. See: Youth Pointing Rifle Slain by Policeman,” Seattle Post Intelligencer, October 6, 1968, 1. and “Youth Fatally Shot in Struggle With Police,” Seattle Times, October 6, 1968, 1.

28 Aaron Dixon Interview.

29Intercommunialism was the idea that capitalism had created a situation where neither national boundaries nor national interests existed. Newton theorized that corporate bodies had colonized nations and regions creating a myriad of oppressed populations throughout the globe. In response, Newton believed that the oppressed needed to unite and attempt to reverse the advances of the capitalist leviathan. Newton and Seale concluded that before any revolution could occur, the oppressed would need to have their basic physical and psychological necessities taken care of. From this belief emerged the Panther survival programs, which represented a tangible shift from militancy to social assistance. See: Mumia Abu-Jamal, “A Life in the Party: An Historical and Retrospective Examination of the Projections and Legacies of the Black Panther Party,” in Liberation, Imagination, and the Black Panther Party: A New Look at the Panthers and Their Legacy, Editors Kathleen Cleaver and George Katsiaficas, 40-50. Great Britain: Routledge, 2001, 49 and Hayes and Kiene, “All Power to the People”, 169-171.

30 JoNina M. Abron, “’Serving the People’: The Survival Programs of the Black Panther Party,” In The Black Panther Party Reconsidered, edited by Charles E. Jones, 177-192, Baltimore: Black Classic Press, 1998, 178-179, and Charles Jones and Judson Jeffereis, “Don’t Believe the Hype”, 31. BPP survival programs that were instituted by BPP chapters around the U.S. included, free breakfast for school children, free clothing program, free bussing to prisons, free medical care, The Black Panther newspaper, sickle cell anemia testing, free pest control, free shoes, free food, free ambulance rides, and a youth institute.

31 Elmer Dixon Interview.

32 Aaron Dixon Interview.

33 “Elmer Dixon; Black Panther Party Breakfast for Children Programs, Seattle, WA, Information Concerning,” (F.B.I. File), July 30, 1969, University of Washington Archives.

34 Elmer Dixon Interview.

35 Hearing Before the Committee on Internal Security, House of Representatives (Black Panther Party, Part 2, Investigation of the Seattle Chapter), May 12, 13, 14, and 20, 1970, 4332, 4366-4367.

36 Leon Hobbs Interview.

37 Bobby Seale, Interviewed by Kurt Kim Schaefer, May 14, 2005.

38 Leon Hobbs Interview.