Exploring Tetiaroa

by Professor Billie J. Swalla, Director of FHL, & Shawn Luttrell, Graduate Student

“Tetiaroa is beautiful beyond my capacity to describe. One could say that Tetiaroa is the tincture of the South Seas.”

- Marlon Brando

This is our collecting site for Ptychodera flava, hemichordate worms that can completely regenerate their body parts. This is just in front of the Brando, a luxury carbon-neutral hotel on Tetiaroa.

Photo credit: Shawn Luttrell

This is our collecting site for Ptychodera flava, hemichordate worms that can completely regenerate their body parts. This is just in front of the Brando, a luxury carbon-neutral hotel on Tetiaroa.

Photo credit: Shawn LuttrellTetiaroa, an atoll in French Polynesia, made world news when Marlon Brando purchased it in 1966 and 1967, from a descendant of Dr. Williams. The royal Pomare family of Tahiti had given the sacred island to Dr. Williams, the only dentist in Tahiti, to thank him for his services to the kingdom. I was only a child then, but remember reading about this special place in the Pacific, and how idyllic it was. Thus, I was pleased to hear that a marine station was being established there for research and teaching, and eagerly agreed to become one of the scientists working and learning from the unique location and environment. The Tetiaroa Society runs the Ecostation, a newly-established and unique marine lab on the Motu Onetahi on Tetiaroa, and I am a member of their Scientific Advisory Board. Atolls are special places; by definition they are coral reefs with small bits of land, called motus, that are usually rich in marine diversity but there is little fresh water on an atoll.

So, why study the biological diversity, ecology, and ocean chemistry of a Tahitian atoll? In an era of global climate change, it is important to understand the effects of changes in the atmosphere and increases in temperatures in multiple places. Moorea and Tetiaroa are far from the San Juan Islands, yet all islands share particular features. Moorea and San Juan Island both have considerable nutrient input from the land, which is not available to the atoll of Tetiaroa. How do the corals thrive or become stressed under the different conditions? How does the environment affect biological diversity? How will environmental changes affect the future of these islands?

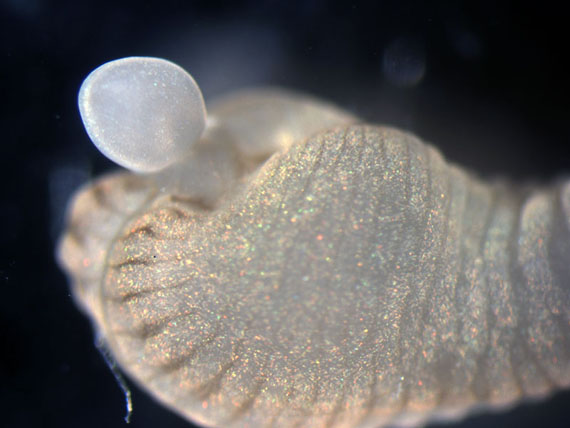

This is the posterior end of a worm that has regenerated its head (proboscis). Notice that the head is white, where new tissue has appeared. The new tissue is perfectly shaped and connected to the back half of the worm. This would be like a human growing a new head after being cut through the waist!

Photo credit: Shawn Luttrell

This is the posterior end of a worm that has regenerated its head (proboscis). Notice that the head is white, where new tissue has appeared. The new tissue is perfectly shaped and connected to the back half of the worm. This would be like a human growing a new head after being cut through the waist!

Photo credit: Shawn LuttrellI headed for French Polynesia this past November with Shawn Luttrell, a graduate student of mine who's researching hemichordate (worm-like marine animals) regeneration. We carried a special bag full of supplies for research done at the Eco Station, and clothes that we hoped were suitable for a South Pacific Island. Our first stop was the Berkeley Gump Marine Lab on Moorea for the Scientific Advisory Board meeting. The Board benefits from members that have expertise in various marine research fields from all over the world, including Australia, and researchers and government officials from French Polynesia (see link to the SAB above). Then Shawn and I flew to Tetiaroa, to see The Brando (a Leed Platinum hotel) and the EcoStation. Shawn stayed on Tetiaroa to begin her research while I went back to Moorea for another day of the Tetiaroa SAB meeting. The Board now meets every two weeks from afar, to discuss new research projects being done by researchers all over the world. This was Marlon Brando’s dream, and now it's becoming a reality.

Some of the scientists working at the Ecostation on Tetiaroa in November 2014. Left to right: Shawn Luttrell, UW Biology and FHL graduate student; Clement Amie the boat driver; Hannah Stewart, Tetiaroa Society; Billie Swalla, Director Friday Harbor Laboratories; Ian Copping.

Photo credit: Shawn Luttrell

Some of the scientists working at the Ecostation on Tetiaroa in November 2014. Left to right: Shawn Luttrell, UW Biology and FHL graduate student; Clement Amie the boat driver; Hannah Stewart, Tetiaroa Society; Billie Swalla, Director Friday Harbor Laboratories; Ian Copping.

Photo credit: Shawn LuttrellShawn is working on the gene networks that are activated when the coral reef hemichordates are cut in two and then completely regenerate their missing body parts. This is leading to new insights into the evolutionary relationships of hemichordates to humans and other invertebrates, and will eventually have medical implications. We are very excited about this new location to carry out our studies. Any sort of new endeavor necessarily involves meeting new people, making new connections, and learning new things about marine science and education. A special thanks to the David Seeley, a member of the Executive Board of the Tetiaroa Society, and to James and Marsha Seeley for their support of this project.