University of Washington in World War I

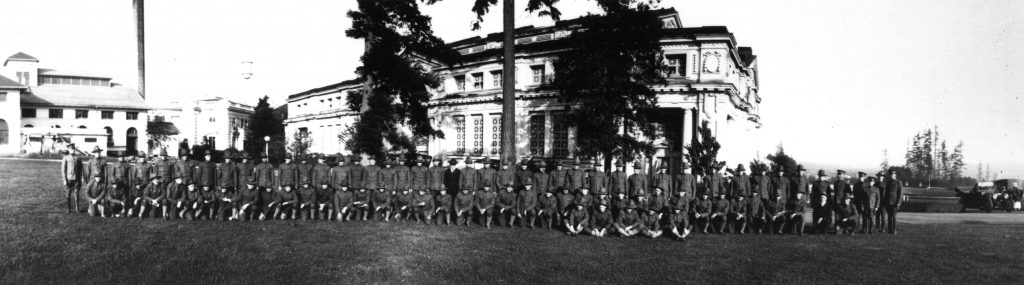

More than 1,500 students and faculty members were enrolled in military service from April 1917, when America entered World War I, until the war ended with an armistice on November 11, 1918. A total of 58 alumni, students and faculty members died in the war. The University of Washington was unique among institutions on the West Coast in offering training for the three military branches: Army, Navy, and Marines. The largest encampment, which took over the golf course on south campus, was dedicated to naval training. Temporary housing arose for more than 700 Navy men, including some who had recently been students and some who were already in the Navy. The space reverted to a golf course after the 1918 armistice. It is now the sit of the Warren G. Magnuson Health Sciences Center and UW Medical Center. (University of Washington, Antoinette Wills and John D. Bolcer).

History of the World War I Monument

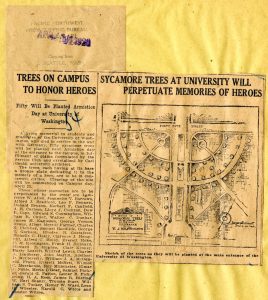

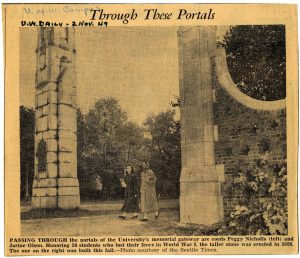

The University of Washington’s World War I Memorial features an arch with two pillars containing a plaque with the 58 names of the fallen soldiers from University of Washington. It also features a long row of fifty-eight London Plane (sycamore) trees dedicated to those soldiers, as tree planting had always been a common tradition of the University. Today, the World War I Memorial has expanded across an entire street, Memorial Way, with a total of 101 trees, and is still well maintained and deeply appreciated by University of Washington staffs, students, and many visitors (Marmor 1).

The University of Washington’s World War I Memorial features an arch with two pillars containing a plaque with the 58 names of the fallen soldiers from University of Washington. It also features a long row of fifty-eight London Plane (sycamore) trees dedicated to those soldiers, as tree planting had always been a common tradition of the University. Today, the World War I Memorial has expanded across an entire street, Memorial Way, with a total of 101 trees, and is still well maintained and deeply appreciated by University of Washington staffs, students, and many visitors (Marmor 1).

Although is it much appreciated today, at first, there was much debate as to whether the University of Washington should dedicate a memorial to its fallen students, staffs, and alumni. But after receiving positive responses about the idea, University of Washington began planning the Memorial with Edmond S. Meany, a professor at the University of Washington who led the project.

On July 11, 1918, Judge Clay Allen contacted Henry Suzzallo and proposed an idea. He suggested that a memorial gate should be constructed in memory of the University’s men and women in the Spanish-American War as well as World War I. Suzzallo responded by explaining that creating a memorial based on similar intentions was already under consideration. The idea was for this memorial to recognize those who were currently in war as well as those who had passed, and will pass. But, however, there was an issue due to a “lack of accurate information.” Suzzallo stated that there had been a decision to create one memorial after the war commemorating all the past and current University members who have passed. He also said that a separate memorial was to be created commemorating those in the Spanish-American War. This correspondence between the two led to the beginnings of the memorial (UW 1).

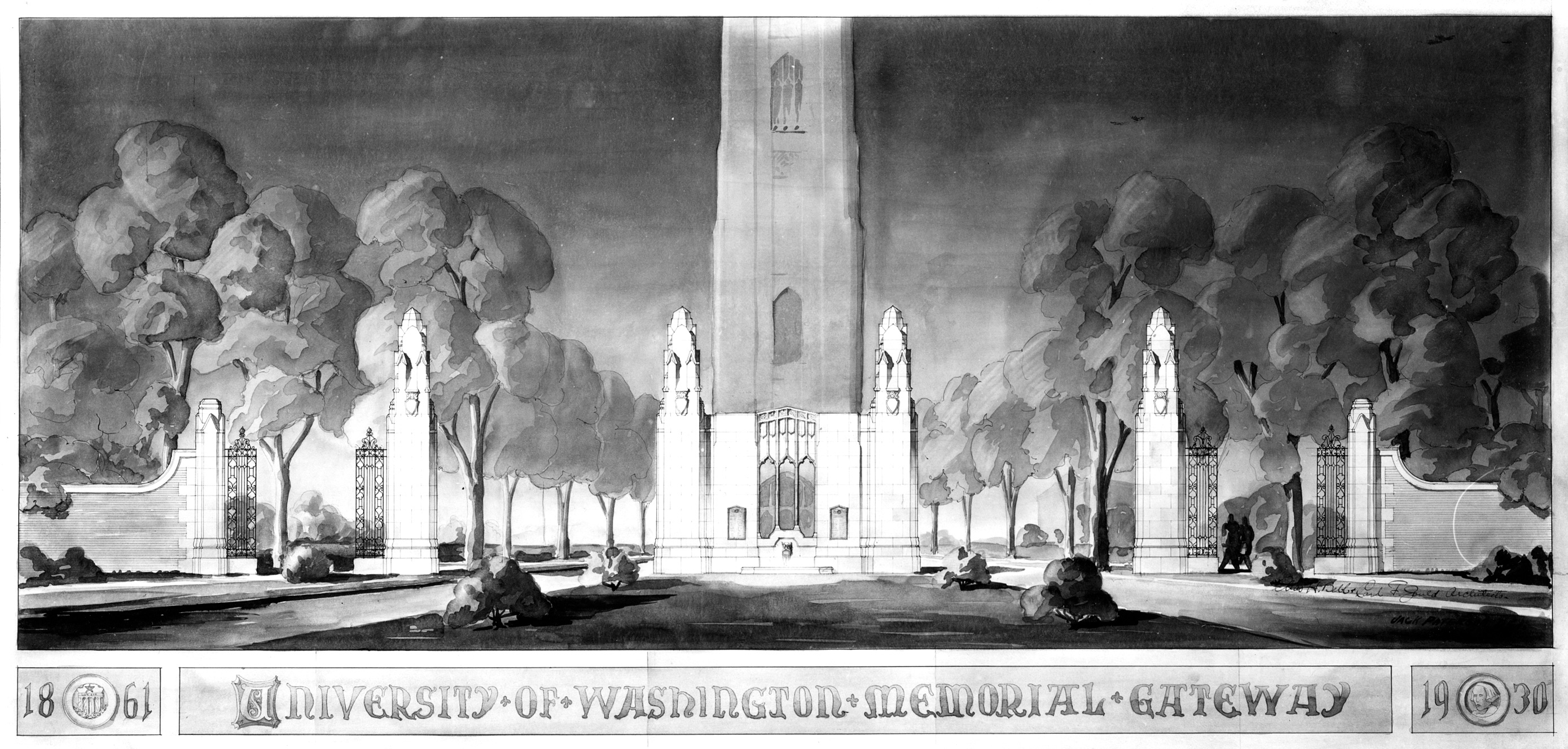

Later, on April 21, 1920, members of the Senior Memorial Committee from the Class of 1920 decided to propose a more direct and specific plan for a Memorial Gate. They chose a location of the memorial, which was an entrance of the campus on Forty-fifth Street and Seventeenth Avenue north-east. Carl F. Gould aided these people in the project by preparing and approving design ideas (Kindig 1).

Later, on April 21, 1920, members of the Senior Memorial Committee from the Class of 1920 decided to propose a more direct and specific plan for a Memorial Gate. They chose a location of the memorial, which was an entrance of the campus on Forty-fifth Street and Seventeenth Avenue north-east. Carl F. Gould aided these people in the project by preparing and approving design ideas (Kindig 1).

Fully aware that the construction of such monument is a demanding process, the committee members suggested that each graduating class, beginning with theirs, contribute in some way. Their idea was to have each graduating class add a part to the gate until it is completed. They also had the idea of each graduating class financially contributing to the project as well, so that no individual group assumes too much financial burden.

Under the supervision of Suzzallo, the planning of the memorial then took off. On Armistice Day, 1920, the planting of the initial trees had occurred. This was followed by an exercise, which took place in Meany Hall. However, many later felt that additional work had to be done. On March 26, 1930, various students, including some from the Oval Club developed interest in further advancing the memorial. They intended to add bronze tablets with the names of those commemorated, as well as raising money for the other additional aspects that are yet to be completed. Because of individuals like these and countless others, the memorial was completed and stands today as a wonderful reminder of the selfless service and heroic actions of those from the University of Washington. World War I was a very important time for the University of Washington. The University’s students and staff contributed to the War greatly and were extremely active participants during that historic time (UW 1).

References

91st Division Publication Committee. The Story of the 91st Division. San Francisco, CA: H.S. Crocker,

1919. Print.

Kindig, Jessie. “Northwest Antiwar History: Chapter 1.” Intro: Labor and WWI. Web. 28 Jan. 2017.

Marmor, John. “March 2002 Columns Magazine Feature: A Place Apart – Memorial Way.” March 2002

Columns Magazine Feature: A Place Apart – Memorial Way. Web. 28 Jan. 2017.

UW Health Sciences Library. UW Health Library. Web. 25 Jan 2017.

The Life Behind the Memorial

Learn about each of the 53 service members represented by the trees along Memorial Drive and on the WWI memorials by clicking below.

Sergeant Lawrence Erwin Allen died of influenza on October 20, 1918, near Bordeaux, France, while attending an Officers’ Training Field Artillery School. A member of the Quartermaster Corps, Lawrence was buried at Suresnes American Cemetery in France. (bit.ly/uw_allen)

Sergeant Lawrence Erwin Allen died of influenza on October 20, 1918, near Bordeaux, France, while attending an Officers’ Training Field Artillery School. A member of the Quartermaster Corps, Lawrence was buried at Suresnes American Cemetery in France. (bit.ly/uw_allen)

Lawrence attended the University of Washington for two years studying mechanical engineering. While at the UW he was a member of Delta Kappa Epsilon Fraternity and captain of the freshman crew under legendary coach Conibear. At the time he registered for the draft he was working for the Jewell Tea Company and living in Pendleton, Oregon.

A native of Waitsburg, Lawrence was one of four children born to Herbert Wilmot Allen, a physician, and his wife, Lena Erwin. He was married to fellow UW student Lulu Jane Wright on July 18, 1916, in Missoula, Montana. A brass vase is dedicated to his memory at the Episcopal Church of the Holy Spirit where Lawrence and Lulu were married. Lulu died just six years later at the age of 29.

It is perhaps fitting that the University of Washington’s fifty-eighth and final Gold Star honors its only female casualty, Jeanette Virginia Barrows. Jeanette died of pneumonia on March 15, 1919, at Fort Snelling in Minnesota. Unlike so many other of the UW’s other Gold Stars, Jeanette’s death was not related to influenza.

It is perhaps fitting that the University of Washington’s fifty-eighth and final Gold Star honors its only female casualty, Jeanette Virginia Barrows. Jeanette died of pneumonia on March 15, 1919, at Fort Snelling in Minnesota. Unlike so many other of the UW’s other Gold Stars, Jeanette’s death was not related to influenza.

The older of two daughters born to William A. Barrows and his wife, Ella Tanger, Jeanette was born and raised in Chinook, Washington. Her father was a political cartoonist for the Chinook Observer and her mother was the town’s longtime postmaster. From her father she inherited a talent for sketching and cartooning. Jeanette entered the UW in 1916, following two years of study at Bellingham State Normal School (now Western Washington University), graduating with a degree in education in 1918. While at the UW, Jeanette was a member of Alpha Delta Pi Sorority and a scholarship is awarded in her honor annually.

After graduating, Jeanette spent the following summer at Reed College training for work as a Reconstruction Aide. Reed College was the only west coast site for Reconstruction Aides which had two courses of study: physiotherapy and occupational therapy. Physiotherapy was aimed at helping wounded soldiers regain the use of lost or impaired functions through remedial exercise and massage. Occupational therapy was designed to aid returned soldiers in their recovery through vocational training. (bit.ly/reed_barrows)

Following completion of her training, Jeanette was sworn into service to the United States on October 24, 1918 and was sent directly to New York. While in New York waiting overseas orders Armistice was signed. A month later she was ordered to US Army General Hospital No. 29 at Fort Snelling to assist in the care of the wounded returned from France. Jeanette died after an illness of only four days and was buried at Ilwaco Cemetery with full military honors. (bit.ly/uw_barrows)

After eight months of training in Dover, England, Sergeant Leo Francis Bennett sailed for home without ever having been called into action. His unit was one of the first AEF forces to be sent home after Armistice was declared. Leo, along with fellow members of the 834th Aviation Squadron, arrived in New York on December 11, 1918, aboard the Empress of Britain. He died just six days later of influenza, after an illness of fifteen hours, at Camp Mills, in Garden City, New York, on December 17, 1918.

After eight months of training in Dover, England, Sergeant Leo Francis Bennett sailed for home without ever having been called into action. His unit was one of the first AEF forces to be sent home after Armistice was declared. Leo, along with fellow members of the 834th Aviation Squadron, arrived in New York on December 11, 1918, aboard the Empress of Britain. He died just six days later of influenza, after an illness of fifteen hours, at Camp Mills, in Garden City, New York, on December 17, 1918.

Leo enlisted in the Air Service at Vancouver Barracks on December 17, 1917. At the time he registered for the draft in August of 1917, he was working as a machinist at a fish cannery in Kenai, Alaska. Born in Andover, South Dakota, Leo and his family moved to Tualco, Washington, near Monroe, in 1902. He graduated from Monroe High School in 1914, and attended the University of Washington for two years. While at the UW, Leo pledged Phi Kappa Fraternity and was active in the Stevens Debating Club.

Leo was one of seven children born to Telman Nestor Bennett and his wife, Lucy Halpin. His brother, Corporal Harry Telman Bennett, was with him at Camp Mills when he died and brought him home where he was buried at the IOOF Cemetery in Monroe. (bit.ly/uw_bennett)

“Run for your life; I’m done for!” were the last words of Lieutenant Cherrill Roach Betterton during the American offensive of September 29, 1918, when the Wild West Division advanced to the village of Gesnes. (Seattle Star, 31 May 1919, pg. 10) During that attack – while traveling with Corporal John Cudd – Cherrill was in an advanced and exposed position when a blast came from a German machine gun. A member of the Intelligence Section responsible for scouting, patrolling, observing and sniping, Cherrill was cited for his bravery by General John J. Pershing for his efforts to get enemy information back to his commanding officers. Last seen when struck by the machine gun’s bullets, Cherrill was declared missing and it would be over eight months before his fate was confirmed. A member of the 361st Infantry with the 91st Division, Cherrill’s remains were eventually recovered and he is buried at Meuse-Argonne Cemetery. (bit.ly/uw_betterton)

“Run for your life; I’m done for!” were the last words of Lieutenant Cherrill Roach Betterton during the American offensive of September 29, 1918, when the Wild West Division advanced to the village of Gesnes. (Seattle Star, 31 May 1919, pg. 10) During that attack – while traveling with Corporal John Cudd – Cherrill was in an advanced and exposed position when a blast came from a German machine gun. A member of the Intelligence Section responsible for scouting, patrolling, observing and sniping, Cherrill was cited for his bravery by General John J. Pershing for his efforts to get enemy information back to his commanding officers. Last seen when struck by the machine gun’s bullets, Cherrill was declared missing and it would be over eight months before his fate was confirmed. A member of the 361st Infantry with the 91st Division, Cherrill’s remains were eventually recovered and he is buried at Meuse-Argonne Cemetery. (bit.ly/uw_betterton)

The oldest of Charles Leland Betterton and his wife Ellen Maude Cahill’s five children, Cherrill was born in Oak Cliff, Texas. The family moved from Texas to Colorado to British Columbia before making their way to Seattle. A graduate of Victoria High School in British Columbia, Cherrill attended the University of Washington for two years (1912-14) before transferring to Stanford University. He was a junior when he enlisted and a member of Sigma Alpha Epsilon Fraternity. Cherrill was married to Ida May MacDonald on December 18, 1916, in Vancouver. Their romance began as a result of a train accident near Merritt, BC, they were both involved in. (Seattle Seattle Times, 24 Dec 1916, pg. 2)

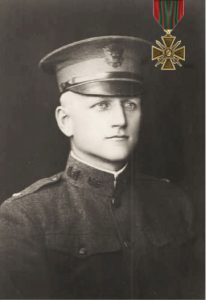

“Gone west” was an expression among WWI aviators indicating a pilot had been killed. Lieutenant Alford John Bradford went west on July 25, 1918, when his plane was shot down in flames while flying in combat on the Western Front. It would be another four months before his wife, Emily Madeline Cheadle, and parents would learn he had been killed, during which time his wife had given birth to their son, John Cheadle Bradford. One of the best aerial observers of his unit, Alford was awarded the French Croix de Guerre posthumously for his service. Created in 1915, the decoration was bestowed on foreign military forces allied to France.

“Gone west” was an expression among WWI aviators indicating a pilot had been killed. Lieutenant Alford John Bradford went west on July 25, 1918, when his plane was shot down in flames while flying in combat on the Western Front. It would be another four months before his wife, Emily Madeline Cheadle, and parents would learn he had been killed, during which time his wife had given birth to their son, John Cheadle Bradford. One of the best aerial observers of his unit, Alford was awarded the French Croix de Guerre posthumously for his service. Created in 1915, the decoration was bestowed on foreign military forces allied to France.

The youngest of four children born to Martin Bradford and Fanny Crooker, Alford was born in Jackson, Michigan. He graduated from Seattle’s Lincoln High and earned a degree in Civil Engineering from the University of Washington in 1915. He was employed at the US Land Office in Juneau, Alaska, surveying the Susitna River, at the time of his enlistment. He married nurse Madeline Cheadle in 1917. At the time of their marriage Alford was an instructor at the Officer Training Camps at Vancouver Barracks. Alford went to France with the Field Artillery before transferring to the American Aviation service. Originally buried in France, Alford was reinterred at Arlington National Cemetery in 1922. (bit.ly/uw_bradford) American Legion Post No. 4 in Juneau is named in honor of Alford John Bradford.

Having seen more than a year of service with the Tenth Engineers (Forestry) Lieutenant Donald Rich Broxon lost his life in a train wreck on December 5, 1918, while en route for home. The accident occurred near Meung-sur-Loire – located between Paris and Tours – when a freight train on a side track backed onto the main track into an oncoming passenger train killing 20 American officers as well as French officers and civilians. He had received news of his commission shortly time before the accident.

Having seen more than a year of service with the Tenth Engineers (Forestry) Lieutenant Donald Rich Broxon lost his life in a train wreck on December 5, 1918, while en route for home. The accident occurred near Meung-sur-Loire – located between Paris and Tours – when a freight train on a side track backed onto the main track into an oncoming passenger train killing 20 American officers as well as French officers and civilians. He had received news of his commission shortly time before the accident.

Born in Fort Wayne, Indiana, Donald moved to Idaho as a young child. He was oldest of Charles Oliver Broxon and Malinda “Linnie” Delight Rich’s four children. A graduate of Hollywood High School in Hollywood, California, Donald entered the University of Washington in 1914 after two years of study at the University of Southern California. He graduated from UW with a MA in forestry in 1916. He was a member of Pi Tau Upsilon Fraternity. Donald served as the first president of the Idaho Club and was active in class football. Donald enlisted immediately upon the outbreak of the war.

The same day his family received a letter from Donald with a picture enclosed of him in his new uniform with his lieutenant stripes came the telegram from the war department bringing the news of his death. “His bright, cheery letter, full of enthusiasm… coming, as it did, almost simultaneously with the telegram bearing the awful news has made it doubly hard to bear.” (Idaho Statesman, Jan 4, 1919, pg. 4.) Donald is buried at Oise-Aisne American Cemetery in France. (bit.ly/uw_broxon)

Of the individuals identified as having either attended or graduated from the University of Washington who served during World War I and made the ultimate sacrifice only one has remained completely elusive to verify any details about his life story: Fred E Bueler. The scant information available comes from the Sixteenth Biennial Report of the Board of Regents which lists him among the UW’s casualties:

F. E. Bueler, lieutenant, 116th Infantry. Died at Lyons, France.

Attempts to locate a roster of the 116th have been unsuccessful. On the UW’s WWI memorial, Fred is listed as F.E. Bueler. He was likely a short term student in a forestry program as he is mentioned in American Forestry, where he is referred to as Fred, with other UW students but efforts to learn more about his life have thus far been unsuccessful.

Herbert Florian Canfield was so determined to enlist he endured sinus surgery requiring a five-week convalescence in order to qualify. He was still rejected twice before he passed and joined the United States Naval Reserve Force as chief quartermaster. (Arkansas Democrat, 14 Sep 1918, pg. 8.) Florian died on August 26, 1918, when his seaplane crashed into Biscayne Bay off the coast of Miami, Florida. His body was brought to Seattle and his funeral was held from the University Methodist Church where his was buried with military honors with a band from the Bremerton Navy Yard and a company from the local Aviation Camp in attendance and “Eddie Hubbard, in an airplane … circle[d] high above the grave during the burial service.” (Seattle Star, 4 Sep, 1918, pg. 5.) Letters from fellow fliers were read at the service with tributes to Herbert’s bravery, daring and fidelity. Herbert was buried in Seattle’s Evergreen-Washelli Cemetery. (bit.ly/uw_canfield)

Herbert Florian Canfield was so determined to enlist he endured sinus surgery requiring a five-week convalescence in order to qualify. He was still rejected twice before he passed and joined the United States Naval Reserve Force as chief quartermaster. (Arkansas Democrat, 14 Sep 1918, pg. 8.) Florian died on August 26, 1918, when his seaplane crashed into Biscayne Bay off the coast of Miami, Florida. His body was brought to Seattle and his funeral was held from the University Methodist Church where his was buried with military honors with a band from the Bremerton Navy Yard and a company from the local Aviation Camp in attendance and “Eddie Hubbard, in an airplane … circle[d] high above the grave during the burial service.” (Seattle Star, 4 Sep, 1918, pg. 5.) Letters from fellow fliers were read at the service with tributes to Herbert’s bravery, daring and fidelity. Herbert was buried in Seattle’s Evergreen-Washelli Cemetery. (bit.ly/uw_canfield)

Herbert registered for the draft in Schenectady, NY, where he was employed at General Electric Company. He accepted the position there following his graduation in 1916 from the UW with a degree in electrical engineering. His undergraduate thesis was titled “Automatic Temperature Control of Induction Water Heater” and he was member of Theta Chi Fraternity. Prior to enlisting he was involved with testing electric controls for the battleship New Mexico while at GE. Herbert was one of eight children born to Herbert Howe Canfield, a physician, and Ada Laughlin. Herbert was born in Siloam Springs, Arkansas and graduated from Seattle’s Lincoln High School. Six of the eight Canfield children attended the University of Washington.

Leading his men across a shell swept ridge, in the Argonne Forest, Arthur Edward Carson, ’18, lieutenant in the 91st Division, was struck by a high explosive, September 29, 1918, adding a paragraph to the deathless fame of the “Wild West” and sharing the glory of its citation for bravery.” (TYEE, 1919, pg. 38.) Second Lieutenant Carlson of the 347th Machine Gun Battalion, 91st Division, was killed in action in France near Verdun. Arthur entered the second officers training camp at the Presidio in August of 1917. He was commissioned as a second lieutenant and reported at Camp Lewis where he was attached to the 347th Machine Gun Company. His company left for France in June, 1918, part of the 91st division. Notice of Arthur’s promotion to first lieutenant was received shortly after he lost his life.

Leading his men across a shell swept ridge, in the Argonne Forest, Arthur Edward Carson, ’18, lieutenant in the 91st Division, was struck by a high explosive, September 29, 1918, adding a paragraph to the deathless fame of the “Wild West” and sharing the glory of its citation for bravery.” (TYEE, 1919, pg. 38.) Second Lieutenant Carlson of the 347th Machine Gun Battalion, 91st Division, was killed in action in France near Verdun. Arthur entered the second officers training camp at the Presidio in August of 1917. He was commissioned as a second lieutenant and reported at Camp Lewis where he was attached to the 347th Machine Gun Company. His company left for France in June, 1918, part of the 91st division. Notice of Arthur’s promotion to first lieutenant was received shortly after he lost his life.

The older of two sons, Arthur was born in Astoria, Oregon, to Finnish natives Frank Robert Carlson and his wife Anna Louise Johnson. The family later moved to Anacortes, Washington, where Arthur graduated from high school in 1914. He enrolled at the University of Washington and was a junior majoring in electrical engineering, affiliated with Acacia Fraternity, at the time of his enlistment. Arthur was united in marriage with Aletta Christine Anderson on March 2, 1918, in Tacoma. Originally buried in France, Arthur was reinterred at Fern Hill Cemetery in Anacortes on September 25, 1921. (bit.ly/uw_carlson)

Seattle-born Lloyd Thomas Cochran was the middle of three sons born to William Cochran and his wife, Lena Sather, a native of Norway. A 1912 graduate of Ballard High School, Lloyd attended the University of Washington graduating with a law degree in 1917. Even before the US entered the war, Lloyd had applied to the first Officers Training School at the Presidio and been awarded a commission. At the time his unit shipped overseas in July of 1918, Lloyd was a 2nd Lieutenant with Company F of the 363rd Infantry Regiment which was part of the 91st Infantry Division — known as the “Wild West Division” — out of Camp Lewis. Lloyd was the first man of Company F to be killed. Cochran was killed by a German sniper as he led his unit in a charge on the first day of the battle of Meuse-Argonne, September 26, 1918.

Seattle-born Lloyd Thomas Cochran was the middle of three sons born to William Cochran and his wife, Lena Sather, a native of Norway. A 1912 graduate of Ballard High School, Lloyd attended the University of Washington graduating with a law degree in 1917. Even before the US entered the war, Lloyd had applied to the first Officers Training School at the Presidio and been awarded a commission. At the time his unit shipped overseas in July of 1918, Lloyd was a 2nd Lieutenant with Company F of the 363rd Infantry Regiment which was part of the 91st Infantry Division — known as the “Wild West Division” — out of Camp Lewis. Lloyd was the first man of Company F to be killed. Cochran was killed by a German sniper as he led his unit in a charge on the first day of the battle of Meuse-Argonne, September 26, 1918.

Just minutes before he and his company had discovered “a German machine gun “nest” with six or eight Germans around it. A German prisoner, who had escaped the bombardment had been captured a half hour before and was questioned sharply. He lied about the location of the machine gun but Cochran said not to handle the prisoner too rough as he would not like to be mistreated himself if a prisoner” as reported in the Seattle Daily Times in a series of articles written by Colin Dyment, Director of the UW’s School of Journalism. (Seattle Daily Times, Apr 14, 1919, pg. 7). Dyment goes on to say the German snipers responsible for Lloyd’s death were “promptly executed”. Originally buried at Bois de Cheppy, in France, Lloyd was reinterred in Seattle’s Evergreen-Washington Cemetery. (bit.ly/uw_cochran) American Legion Post No. 40 in Ballard is named in his honor. (www.facebook.com/BallardPost40)

Lieutenant Dow Russell Cope, Aviation Section Signal Reserve Corps, was killed when his plane crashed near Tours, France, on June 16, 1918. Some newspaper accounts recorded his death as one of the first aviators to die while serving in Europe. He had recently been commissioned a lieutenant. A son of Walter Cope and Inez Mallory, Dow was born in Salem, Illinois, one of five children. He grew up in Yakima where he graduated from Yakima High School. A gifted debater, he was a member of the Stevens Debating Club at the University of Washington which he attended for one year as a Freshman in Liberal Arts. While at the UW, he also a popular boxing instructor at Seattle’s YMCA.

Lieutenant Dow Russell Cope, Aviation Section Signal Reserve Corps, was killed when his plane crashed near Tours, France, on June 16, 1918. Some newspaper accounts recorded his death as one of the first aviators to die while serving in Europe. He had recently been commissioned a lieutenant. A son of Walter Cope and Inez Mallory, Dow was born in Salem, Illinois, one of five children. He grew up in Yakima where he graduated from Yakima High School. A gifted debater, he was a member of the Stevens Debating Club at the University of Washington which he attended for one year as a Freshman in Liberal Arts. While at the UW, he also a popular boxing instructor at Seattle’s YMCA.

Dow later enrolled at Cumberland College in Lebanon, Tennessee where he studied music, played football and later pursued a law degree. Dow had the distinction of playing for Cumberland on October 7, 1916, when the Georgia Tech Yellow Jackets — known as the “Golden Tornado” and coached by John Heisman — beat the Cumberland Bulldogs 222-0 in the most lopsided-victory in the history of college football. A member of Lambda Chi Alpha Fraternity, Dow was working as a lawyer at Fort Oglethorpe, in Georgia at the time of his enlistment. Originally buried in France, Dow’s remains were repatriated to the US in 1920 and he was laid to rest at Tahoma Cemetery in Yakima. (bit.ly/uw_cope)

Musician Edward Charles Cunningham died of pneumonia following influenza at an Officers’ Training Camp in France on December 1, 1918. He entered the University of Washington as a freshman in Mechanical Engineering in 1916, a member of the Class of 1920. Like so many others, he enlisted following the declaration of war in April of 1917.

Musician Edward Charles Cunningham died of pneumonia following influenza at an Officers’ Training Camp in France on December 1, 1918. He entered the University of Washington as a freshman in Mechanical Engineering in 1916, a member of the Class of 1920. Like so many others, he enlisted following the declaration of war in April of 1917.

Following his enlistment he was sent to Camp Murray – home of the Washington National Guard – for training. He was sent overseas on December 12, 1917, with the 161st Infantry, 41st Division, as a member of the Infantry Band. His high standing as a soldier won him an appointment to the Officers’ Training Camp, but he died before completing the course.

An Honor Roll published by Whitman County, states he was the son of Mr. and Mrs. William Cunningham of St. John, Washington, but additional family details have not been located. Edward is buried at Oise-Aisne American Cemetery in France. (bit.ly/uw_cunningham)

On November 18, 1917 – at just 21 years-old – William Reynolds Cutler was killed in action when his plane crashed near Etaples, France, while serving with the 70th Squadron of the Royal Flying Corps. As a pilot with the “English Camels” – known as the “eyes” of the Allies – Cutler performed the most dangerous scouting duties. (1919 Tyee, pg. 43.) His military career was short but brilliant. He is buried at Etaples Military Cemetery (bit.ly/uw_cutler) near Boulogne.

On November 18, 1917 – at just 21 years-old – William Reynolds Cutler was killed in action when his plane crashed near Etaples, France, while serving with the 70th Squadron of the Royal Flying Corps. As a pilot with the “English Camels” – known as the “eyes” of the Allies – Cutler performed the most dangerous scouting duties. (1919 Tyee, pg. 43.) His military career was short but brilliant. He is buried at Etaples Military Cemetery (bit.ly/uw_cutler) near Boulogne.

The son of Melville Fixott Cutler and Isabella Maud Woodill, Bill was a native of Victoria, British Columbia. He was the first airman casualty from Victoria High School. A member of Sigma Chi at the University of Washington, Bill was active in wrestling and track and majoring in chemical engineering. A poem dedicated to Cutler, composed by classmate Don Rockwell, ’17, was published in the 1918 Tyee and concludes:

Bill Cutler, bright, brave little star,

You gave your life to point the war

For those who fought like men at night

Your eyes for them the only sight—

Bill Cutler, bright, brave little star,

Who fell from high in this great war.

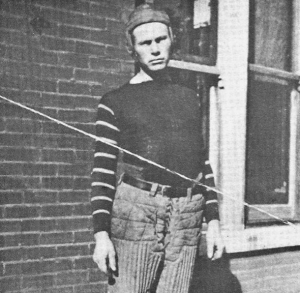

Influenza claimed the life of another well-known UW athlete, Sergeant Walter Clifford Dunbar, of Company B, 161st Infantry. Walter died of pneumonia following influenza on December 30, 1918 in France. Walter went overseas with the 161st in December of 1917. A native of Michigan, Walter was one of five children born to William Henry Dunbar and Nellie Catherine Doust. Walter was a 1910 graduate of Seattle High School — where he was known as Skinny — and then worked his way through the School of Mines at the University of Washington. His 1911 undergraduate thesis was titled “Excavation of ground and timbering used during construction of the north trunk sewer in Seattle, Washington.”

Influenza claimed the life of another well-known UW athlete, Sergeant Walter Clifford Dunbar, of Company B, 161st Infantry. Walter died of pneumonia following influenza on December 30, 1918 in France. Walter went overseas with the 161st in December of 1917. A native of Michigan, Walter was one of five children born to William Henry Dunbar and Nellie Catherine Doust. Walter was a 1910 graduate of Seattle High School — where he was known as Skinny — and then worked his way through the School of Mines at the University of Washington. His 1911 undergraduate thesis was titled “Excavation of ground and timbering used during construction of the north trunk sewer in Seattle, Washington.”

Walter was coxswain of the varsity rowing club for three years and went to Poughkeepsie under Coach Conibear where the Washington boat took an impressive third place. Dunnie, as he was known at the UW, was the captain of the rowing team, a class officer, and contributor to both the Pacific Wave (the precursor to The Daily) and the UW’s yearbook, the Tyee. He was considered as a rowing coach for UC Berkeley but went on to receive a Masters in Civil Engineering from the UW instead. Walter is buried at St. Mihiel American Cemetery in France. (bit.ly/uw_dunbar)

Lieutenant James Mills Eagleson, of the 69th Coast Artillery Corps, died of pneumonia following influenza on February 19, 1919, at Newport News, Virginia. He had just returned, together with his unit, from France. En route he contracted influenza and his condition quickly worsened. A telegram was sent from the USS Mercury to the ship — also in the midst of a transatlantic crossing — conveying his father, Dr. James Eagleson, home following his service with the AEF as medical director of Base Hospital 50. Dr. Eagleson’s ship made port in New York first and he raced to Virginia, arriving in time to be there when his son’s ship docked. James died shortly after his ship reached Newport News with his father by his side.

Lieutenant James Mills Eagleson, of the 69th Coast Artillery Corps, died of pneumonia following influenza on February 19, 1919, at Newport News, Virginia. He had just returned, together with his unit, from France. En route he contracted influenza and his condition quickly worsened. A telegram was sent from the USS Mercury to the ship — also in the midst of a transatlantic crossing — conveying his father, Dr. James Eagleson, home following his service with the AEF as medical director of Base Hospital 50. Dr. Eagleson’s ship made port in New York first and he raced to Virginia, arriving in time to be there when his son’s ship docked. James died shortly after his ship reached Newport News with his father by his side.

James was the oldest of four children born to James Beaty Eagleson and his wife, Clara Blanche Mills. A native of Seattle, “Jimmie” was a graduate of Broadway High School. He graduated from the University of Washington in 1917 with a degree in science. At the UW, Eagleson served a term as yell king and was a member of Phi Gamma Delta Fraternity. James married UW classmate Mary Geneva Sims in Seattle on November 24, 1917. James attended the first Officers’ Training School at the Presidio and graduated with a commission of second lieutenant. He was attached to the 69th Artillery at Fort Casey, where he was promoted to first lieutenant. In July, 1918, he accompanied his unit abroad. Several weeks later, Geneva gave birth to their son, James Sims Eagleson, in Seattle.

Several years after his death, James’ parents set about building a new YMCA for the UW community. Eagleson Hall, home of the YMCA at the University of Washington, was dedicated to the memory of James in March of 1923. Four-year-old James Sims Eagleson led the ceremonial groundbreaking in June of 1922 and Eagleson Hall was completed at a cost of $100,000, including furnishings, in 1923. It remained the home of the YMCA until it was sold to the University in 1963. James is buried at Seattle’s Lake View Cemetery together with his parents. (bit.ly/uw_eagleson)

During the influenza epidemic in Seattle “one enlisted member of the SATC died subsequently, failing to survive a hospital operation necessitated by after complications.” (The Fifteenth Biennial Report of the Board of Regents of the University of Washington to the Governor of Washington, January 1919, pg. 16.) That soldier was Private George Vernon Evans who died November 20, 1918, at Providence Hospital after surgery to treat an empyema (lung abscess) following influenza.

During the influenza epidemic in Seattle “one enlisted member of the SATC died subsequently, failing to survive a hospital operation necessitated by after complications.” (The Fifteenth Biennial Report of the Board of Regents of the University of Washington to the Governor of Washington, January 1919, pg. 16.) That soldier was Private George Vernon Evans who died November 20, 1918, at Providence Hospital after surgery to treat an empyema (lung abscess) following influenza.

When thinking of ways in which colleges could contribute to the war in a greater way, the Student Army Training Corps (SATC) was formed to establish a military unit in every college that could furnish a minimum of one hundred able-bodied men of military age. The Student Army Training Corps (SATC) was established by act of Congress in August, 1918, to train young men to fill positions in the military which was viewed as a top priority for universities. This gave students the chance to take part in a collegiate, learning atmosphere while also training to become a soldier. The SATC was jointly administered by the military at 157 colleges and universities.

George was the youngest of three boys born to Jerome Henry Evans and Matilda Louise Schmidt. Born in Winona, Minnesota, George and his family moved to Yakima when he was a child. George registered for the draft in September, 1918, and had just begun the SATC program when the influenza epidemic hit. George died just one month shy of his 20th birthday and is buried at Tahoma Cemetery in Yakima. (bit.ly/uw_evans)

Corporal Albert Merrill Farmer, a member of the 105th Aero Squadron with the Spruce Production Divisions died on pneumonia following influenza at Vancouver Barracks on November 15, 1918. Albert is buried at Seattle’s Lake View Cemetery, together with his parents. (bit.ly/uw_farmer)

Corporal Albert Merrill Farmer, a member of the 105th Aero Squadron with the Spruce Production Divisions died on pneumonia following influenza at Vancouver Barracks on November 15, 1918. Albert is buried at Seattle’s Lake View Cemetery, together with his parents. (bit.ly/uw_farmer)

Born in Chicago, Albert was the only surviving child of Robert W. Farmer and his wife, Mary Ann Walker Crockett, natives of Canada and Scotland respectively. The family moved west to Seattle in 1906 where Albert attended Broadway High School. He graduated from the University of Washington with a degree in Civil Engineering in 1916.

In 1914, Albert was united in marriage with Clara Bargett Reinicke in Tacoma. Clara was a painter of some renown and inventor. She married for a second time and known professionally as Clara Reinicke Dripps.

“Working day and night to take care of a number pneumonia patients that poured into Base Hospital 50” Private Charles Norman Fletcher contracted the disease and died on October 9, 1918; two days later. (Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 28 Nov 1918.) At the time of his death he was ward master in the hospital, responsible for the patients and the enlisted staff. He was buried in the Army cemetery at Mesves, in the department of Nievre, his name inscribed in a notebook of burials by chaplain Bergen Hansen. He was later reinterred in Seattle’s Lake View Cemetery. (bit.ly/uw_fletcher)

“Working day and night to take care of a number pneumonia patients that poured into Base Hospital 50” Private Charles Norman Fletcher contracted the disease and died on October 9, 1918; two days later. (Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 28 Nov 1918.) At the time of his death he was ward master in the hospital, responsible for the patients and the enlisted staff. He was buried in the Army cemetery at Mesves, in the department of Nievre, his name inscribed in a notebook of burials by chaplain Bergen Hansen. He was later reinterred in Seattle’s Lake View Cemetery. (bit.ly/uw_fletcher)

At the time he registered for the draft, Charles was working at a salmon cannery in Dundas Bay, Alaska. One of the first to enlist after the organization of the base hospital in Seattle, by Major James B. Eagleson, Charles withdrew during his sophomore year at the UW to enlist having previously been rejected in earlier attempts to enlist in either the infantry or artillery. Born in Buckley, Washington, Charles was survived by his mother and father, Anna and Charles Fletcher, natives of Scotland and English, respectively and an older sister. He death was the first gold star for his fraternity Kappa Sigma. Charles was a graduate of Broadway High School.

First Lieutenant Samuel Goodglick, U.S. Army Medical Corps, was an army surgeon in charge of the Coos Bay district, and after vigil of nights and days in caring for influenza victims among the soldiers in the spruce-camp, was himself stricken. He died of bronchopneumonia following influenza in North Bend, Oregon on November 8, 1918. “Funeral services for First Lieutenant Samuel Goodglick, of the Army Medical Corps, whose devotion to duty in caring for influenza victims in the many spruce camps of the Coos Bay district is considered the cause of his own death.” (Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 12 Nov 1918) He is buried at Bikur Cholim Cemetery in Seattle. (bit.ly/uw_goodglick)

First Lieutenant Samuel Goodglick, U.S. Army Medical Corps, was an army surgeon in charge of the Coos Bay district, and after vigil of nights and days in caring for influenza victims among the soldiers in the spruce-camp, was himself stricken. He died of bronchopneumonia following influenza in North Bend, Oregon on November 8, 1918. “Funeral services for First Lieutenant Samuel Goodglick, of the Army Medical Corps, whose devotion to duty in caring for influenza victims in the many spruce camps of the Coos Bay district is considered the cause of his own death.” (Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 12 Nov 1918) He is buried at Bikur Cholim Cemetery in Seattle. (bit.ly/uw_goodglick)

Born in New York, Samuel moved to Seattle at a young age and graduated from Broadway High School. He was the middle child of Meyer Goodglick and Gertrude Anna Sperling’s seven children. He studied for two years at the University of Washington, between 1910 and 1912, completing his education at Columbia University. He studied then medicine at the College of Physicians and Surgeons, also at Columbia. Following his graduation from medical school, he served for two years in Lincoln Hospital in New York City. Volunteering in the army as a private, he was later commissioned and promoted to the rank of first lieutenant.

Private George Congdon Gorham was killed instantly by enemy shell fire on October, 10, 1918, near the village of Escaudœuvres. George was a member of the 1st Canadians, Motor Machine Brigade, Bordon Battery. He enlisted with the Canadian Expeditionary Force on April 27, 1917, in Winnipeg, Manitoba, and shipped to England in August 1917. George was a student in the College of Forestry and would have graduated in 1916, but left the UW to enlist in Canada prior to the entry of the United States into the war. He is buried at Cantimpre Canadian Cemetery in France. (bit.ly/uw_gorham)

Private George Congdon Gorham was killed instantly by enemy shell fire on October, 10, 1918, near the village of Escaudœuvres. George was a member of the 1st Canadians, Motor Machine Brigade, Bordon Battery. He enlisted with the Canadian Expeditionary Force on April 27, 1917, in Winnipeg, Manitoba, and shipped to England in August 1917. George was a student in the College of Forestry and would have graduated in 1916, but left the UW to enlist in Canada prior to the entry of the United States into the war. He is buried at Cantimpre Canadian Cemetery in France. (bit.ly/uw_gorham)

George was named for his grandfather, a prominent California politician, newspaper editor and Mayflower descendant. Born in Seattle, his parents were William Hills Gorham, a lawyer, and Kathleen Mary Louise Walton, a native of Ireland. George was the oldest of five children, with four younger sisters. He was a 1912 graduate of Broadway High School. While at the UW, he was a member of the Sigma Alpha Epsilon Fraternity. The Gorham family were members of Seattle’s University Unitarian Church and George was the first gold star for their congregation. (Unitarians in the State of Washington, 1870-1960, pg. 169.)

Immediately following the declaration of war, Rhodes Harold Gustafson, a freshman in Liberal Arts, withdrew from classes along with dozens of other students in order to enlist in the University of Washington’s newly formed ambulance unit. The unit was made up entirely of UW students who began drilling and training for hospital service without delay. Their equipment was purchased through donations made by Seattle and Tacoma merchants.

Immediately following the declaration of war, Rhodes Harold Gustafson, a freshman in Liberal Arts, withdrew from classes along with dozens of other students in order to enlist in the University of Washington’s newly formed ambulance unit. The unit was made up entirely of UW students who began drilling and training for hospital service without delay. Their equipment was purchased through donations made by Seattle and Tacoma merchants.

Headed by Professor of Hygiene and University Health Officer David C. Hall, the newly formed Ambulance Corps No. 12, was sent to Allentown, Pennsylvania, for training where Rhodes died of pneumonia on 27 March 1918. (bit.ly/uw_gustafson) The unit trained there until shortly after Rhodes’ death, when the UW’s ambulance corps – now organized as Ambulance Service Sections 570, 571 and 572 – received their long-awaited transfer to active duty in Italy.

Born in St. Louis, Rhodes was the son of Charles Gustafson and Danish-born Hansina Hansen. A talented debater, Rhodes was a graduate of Broadway High School and was active in the Episcopal Church and the Brotherhood of St. Andrew. His older brother Raymond Carl Gustafson also served in WWI, with Evacuation Hospital No. 26.

Corporal Daniel Norman Hart was killed in action in early November, 1918, in the Meuse-Argonne offensive. In the fog of the final days of the war Dan was first reported as severely wounded. By December he was reported as Missing in Action. It would not be until February, 1919, that his family would learn definitively he had been killed on November 2, 1918, while serving with the 23rd Infantry, 2nd Division.

Corporal Daniel Norman Hart was killed in action in early November, 1918, in the Meuse-Argonne offensive. In the fog of the final days of the war Dan was first reported as severely wounded. By December he was reported as Missing in Action. It would not be until February, 1919, that his family would learn definitively he had been killed on November 2, 1918, while serving with the 23rd Infantry, 2nd Division.

Dan was born and raised in Auburn, Washington, one of David Hart and Anna Dingler’s four children. Anna was David’s second wife and she divorced him in 1897 when Dan was four years old, supporting herself and her children as a seamstress. He enlisted just six months after enrolling at the University of Washington, where he had begun a course of study in Liberal Arts. Dan is buried at Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery in France. (bit.ly/uw_hart)

Scarcely a decade after Orville and Wilbur Wright’s first flight at Kitty Hawk, NC, airplanes had already become incorporated into modern warfare. Nicholas Paul Comeford Healy, Class of 1920, responded to the call for aviators in November, 1917, and applied for commission in the Signal Corps. Nicholas was sent almost immediately to Berkeley, CA, for instruction and from there to the Signal Corps Aviation School at Rockwell Field, San Diego. He made rapid progress in flight school and was declared qualified to fly solo.

Scarcely a decade after Orville and Wilbur Wright’s first flight at Kitty Hawk, NC, airplanes had already become incorporated into modern warfare. Nicholas Paul Comeford Healy, Class of 1920, responded to the call for aviators in November, 1917, and applied for commission in the Signal Corps. Nicholas was sent almost immediately to Berkeley, CA, for instruction and from there to the Signal Corps Aviation School at Rockwell Field, San Diego. He made rapid progress in flight school and was declared qualified to fly solo.

On a training flight on May 3, 1918, Healy’s Curtiss Jenny (JN-4D) crashed near La Jolla. According to accounts “the airplane fell in a spinning nose dive from an altitude of about 500 feet after the cadets made a dip for landing for some unknown reason and started up.” (Leavenworth Times, 4 May 1918) A cadet flying with him, Emmett O’Hanley merely suffered a broken ankle.

Nicholas was one of six children born to Nicholas Caine Healy, a prominent pioneer lumberman, and his wife Estella Comeford. Born in Marysville, he was a graduate of Broadway High School and briefly attended Washington State College. The UW sophomore was studying liberal arts and was a member of Sigma Alpha Epsilon Fraternity. Nicholas was buried with full military honors at Seattle’s Lake View Cemetery and his death came just days before he was to receive his commission. (bit.ly/uw_healy)

Lieutenant Clarence Joseph Hemphill died of pneumonia on February 22, 1919, at Evacuation Hospital 21, near Rimaucourt, France. He served with the 1st Army within the 26th Division and was sent to France in January, 1918. Later he was with the 101st Field Artillery and saw action at Chateau Thierry and Verdun. He was gassed three times, the last attack occurring the day before the Armistice signing. “At the time of the last attack he was a liaison officer, not being in physically fit condition to assume command of his battery. While some apprehension had been felt because of his continued presence in a hospital, he had never written home of his condition, and the news of his death came with heartbreaking force.” (Seattle Daily Times, March 19, 1919, pg. 14) Clarence is buried at Meuse-Argonne Cemetery in France. (bit.ly/uw_hemphill)

Lieutenant Clarence Joseph Hemphill died of pneumonia on February 22, 1919, at Evacuation Hospital 21, near Rimaucourt, France. He served with the 1st Army within the 26th Division and was sent to France in January, 1918. Later he was with the 101st Field Artillery and saw action at Chateau Thierry and Verdun. He was gassed three times, the last attack occurring the day before the Armistice signing. “At the time of the last attack he was a liaison officer, not being in physically fit condition to assume command of his battery. While some apprehension had been felt because of his continued presence in a hospital, he had never written home of his condition, and the news of his death came with heartbreaking force.” (Seattle Daily Times, March 19, 1919, pg. 14) Clarence is buried at Meuse-Argonne Cemetery in France. (bit.ly/uw_hemphill)

Clarence was working in the Bay Area at the time he registered for the draft, having previously served in the California National Guard with General Pershing along the Mexican Border in 1916. Following his enlistment, Clarence attended the first Officers Training Camp at the Presidio. The third of William Nelson Hemphill and Harriet Elizabeth “Abbie” Brannan‘s six children, Clarence was born and raised in Auburn, Washington. He graduated from Auburn High School in 1909 and attended the University of Washington from 1912-1914 where he was a member of Acacia Fraternity.

Alfred Clarence Hoiby, ’18, was the only child of Norwegian immigrants Peter Arenson Hoiby (originally Hoideby) and Ida Evenson. Born in Madison, Wisconsin, Alfred and his parents moved west between 1905 and 1910 and he was a 1914 graduate of Broadway High School. While majoring in liberal arts, in preparation for pursuing a law degree, Alfred also turned out for basketball and crew at the University of Washington.

Alfred Clarence Hoiby, ’18, was the only child of Norwegian immigrants Peter Arenson Hoiby (originally Hoideby) and Ida Evenson. Born in Madison, Wisconsin, Alfred and his parents moved west between 1905 and 1910 and he was a 1914 graduate of Broadway High School. While majoring in liberal arts, in preparation for pursuing a law degree, Alfred also turned out for basketball and crew at the University of Washington.

Alfred enlisted upon the declaration of war, near the end of his third year at the UW. He trained with the Coast Artillery Corps, 7th Company, at a Puget Sound coastal fort until his unit was sent to Montana to provide protection for Butte’s copper mines; their uninterrupted output critical to the war effort.

Alfred died in Butte on 10 December 1917 of complications from pneumonia. His mother Ida escorted his body back to Seattle where he was buried at Seattle’s Lake View Cemetery. (bit.ly/uw_hoiby) He made his home with his parents at 1909 Minor Avenue, Seattle. A member of Psi Upsilon Fraternity, the house was named Hoiby Hall in his honor.

On July 27, 1918, Mrs. Catherine Hoke of Seattle received a telegram from the War Department informing her that her son, Thomas Everett Hoke, was missing in action near Chateau Thierry, France. It would be six long months before the news would come that Everett had been killed in action on July 1st. A member of Company A of the 161st Infantry, Hoke had recently been promoted to the rank of Sergeant. He was buried at Aisne-Marne American Cemetery in France. (bit.ly/uw_hoke)

On July 27, 1918, Mrs. Catherine Hoke of Seattle received a telegram from the War Department informing her that her son, Thomas Everett Hoke, was missing in action near Chateau Thierry, France. It would be six long months before the news would come that Everett had been killed in action on July 1st. A member of Company A of the 161st Infantry, Hoke had recently been promoted to the rank of Sergeant. He was buried at Aisne-Marne American Cemetery in France. (bit.ly/uw_hoke)

Born in Tacoma, Everett was the younger of Michael Hoke and Catherine Jones’ two sons. He had resided in Seattle for several years with his widowed English-born mother and brother following his graduation from Olympia High School. His brother Sergeant Herbert Sumner Hoke served with the 69th Artillery. Everett was employed at the Seattle Hardware Company at the time of his enlistment. He had enrolled as a freshman at the University of Washington in 1914 studying Liberal Arts.

Influenza claimed yet another victim, First Lieutenant Earl Malcolm Hoisington, on November 10th, 1918. While recovering from a hunting accident, influenza settled in his lungs and developed into double pneumonia. Earl died at Rockwell Field, near San Diego, California. To honor his excellence in fulfilling his duties, the posthumous rank of captain was conferred upon him. He attended the Second Officers’ Training Camp at the Presidio in August, 1917. Earl was commissioned a first lieutenant and ordered to Camp Lewis following his training. He later transferred to the aviation corps, being one of the few who made this change without a demotion in rank. After ground work training at Austin, Texas, Earl undertook flight work at Rockwell, Otay Mesa and Oneonta Fields. In July, 1918, he was made chief instructor of aerial gunnery, and in that capacity had supervision over four flying fields.

Influenza claimed yet another victim, First Lieutenant Earl Malcolm Hoisington, on November 10th, 1918. While recovering from a hunting accident, influenza settled in his lungs and developed into double pneumonia. Earl died at Rockwell Field, near San Diego, California. To honor his excellence in fulfilling his duties, the posthumous rank of captain was conferred upon him. He attended the Second Officers’ Training Camp at the Presidio in August, 1917. Earl was commissioned a first lieutenant and ordered to Camp Lewis following his training. He later transferred to the aviation corps, being one of the few who made this change without a demotion in rank. After ground work training at Austin, Texas, Earl undertook flight work at Rockwell, Otay Mesa and Oneonta Fields. In July, 1918, he was made chief instructor of aerial gunnery, and in that capacity had supervision over four flying fields.

The older of two children born to Phillip Burlingham Hoisington and Eva Elizabeth Weger, Earl was a native of Spokane. He was a member of the class of 1918, studying business administration at the University of Washington. Earl was an active supporter of the YMCA and a member of Sigma Alpha Epsilon Fraternity. Earl was working as a bookkeeper in Wallace, Idaho, at the time he registered for the draft. In 1925, a portion of Parkwater Field (now Felts Fields) in Spokane was designated headquarters for the 116th Observation Squadron of the Washington Air National Guard and named Camp Earl Hoisington (also known as Earl Hoisington Field). Earl is buried at Spokane’s Moran Cemetery along with other members of the Hoisington family. (bit.ly/uw_hoisington)

Frank Harold Hubbard, ’20, corporal in Company L, 161st United States Infantry, died of scarlet fever at Base Hospital No. 9, Chateauroux, France, on 27 January 1918.

Frank Harold Hubbard, ’20, corporal in Company L, 161st United States Infantry, died of scarlet fever at Base Hospital No. 9, Chateauroux, France, on 27 January 1918.

Corporal Hubbard served on the Mexican border with the Second Washington during the summer of 1916. Upon the declaration of war he was again called into service. After a period of training, his unit left Camp Mills, New York, in December of 1917 and landed in France the first day of 1918. Originally buried in the American plot of the cemetery at Chateauroux, Frank was reinterred at San Francisco National Cemetery in 1920. (bit.ly/uw_hubbard)

Frank was the only child of Kenneth Hubbard and Emma Freeman. Born in Chicago, Frank and his parents later moved to Seattle. He was a 1916 graduate of Lincoln High School. Kenneth Hubbard received a pharmacy degree from Northwestern University and while at the UW Frank followed in his father’s footsteps studying chemistry and pharmacy. He was a pledge of Sigma Nu which named their fraternity house Hubbard Hall in his honor. The Hubbard family lived at 7200 Woodlawn Avenue.

Howard DeHart Hughes first was a Harvard man, Class of 1904. Following his graduation he entered the University of Washington’s Law School graduating in 1907. He worked for several years as an attorney for the City of Seattle, later opening his own law practice, following in his father’s footsteps. One of two children, Howard was born in Carthage, Illinois, to Elwood Clark Hughes and his wife, Emma Jane DeHart.

Howard DeHart Hughes first was a Harvard man, Class of 1904. Following his graduation he entered the University of Washington’s Law School graduating in 1907. He worked for several years as an attorney for the City of Seattle, later opening his own law practice, following in his father’s footsteps. One of two children, Howard was born in Carthage, Illinois, to Elwood Clark Hughes and his wife, Emma Jane DeHart.

He entered the first Officers’ Training Camp at the Presidio in 1917 and was commissioned a captain. He was assigned to the 361st Infantry, 91st Division, and was killed in action on November 1, 1918, at Woertigem, Belgium during the Lys-Scheldt Offensive. He was conferring with the unit’s colonel when both were hit by a shell.

He told his brother-in-law who he had chanced to meet up with in France he expected to be killed and that he “had a personal conviction that he would never return to America.” (Memoirs of The Harvard Dead In The War Against Germany) Originally buried in Belgium, he was reinterred at Arlington National Cemetery. (bit.ly/uw_hughes) He was awarded the Silver Star for his “distinguished and conspicuous ability in handling his company.” (Congressional citation)

Captain Francis David Johnson was killed in action near Bois de la Grande Montagne, as part of the Meuse-Argonne offensive, just two days before the war ended on November 9, 1918. At 6am that morning Captain Johnson headed for hill 378, called Borne de Cornouiller by the French. He was heroically killed as he led his men as they attempted to locate and capture nests of concealed machine guns and snipers. Francis is buried at Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery. (bit.ly/uw_johnson)

Captain Francis David Johnson was killed in action near Bois de la Grande Montagne, as part of the Meuse-Argonne offensive, just two days before the war ended on November 9, 1918. At 6am that morning Captain Johnson headed for hill 378, called Borne de Cornouiller by the French. He was heroically killed as he led his men as they attempted to locate and capture nests of concealed machine guns and snipers. Francis is buried at Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery. (bit.ly/uw_johnson)

After failing to pass the physical examination while at attending officers training camp at the Presidio in the summer of 1917, Francis enlisted as a private in the Engineers. He was later re-examined and commissioned Second Lieutenant. He was promoted to First Lieutenant, while serving with the 316th Infantry, in France. Francis was posthumously promoted to Captain. “‘Alaska’ Johnson, as he was called by his friends, was one of the best loved officers in the regiment.” (History of the 316th Regiment of Infantry in the World War, 1918.)

Born in Wahoo Nebraska, Francis was the only child of Judge Charles Sumner Johnson and his wife, Mary Davis. Francis spent several years of his early childhood in Alaska, where his father was the U.S. District Attorney and later Federal Judge for the District of Alaska with headquarters at Sitka. After his father died in 1906, Francis and his mother settled in Zillah, Washington.

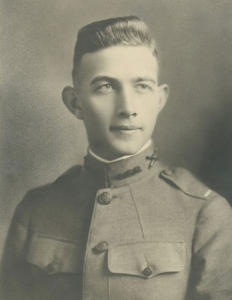

For extraordinary heroism in battle, First Lieutenant Clair Arthur Rawson Kinney, of the 49th Aero Squadron, United States Army Air Service, was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. “With a patrol of six other machines Lieutenant Kinney attacked 17 enemy planes, (Fokker type). Diving into the midst of the enemy formation he fired into one of the German planes, and pursued it until it crashed to the ground, though he was wounded by another Fokker, which attacked him from the rear. After maneuvering to escape his pursuer, Lieutenant Kinney immediately attacked another enemy plane directly in front of him, and forced it to the ground. In so doing he was fired upon from behind by another Fokker, several bullets striking him in the body and another setting fire to his gas tank. He succeeded in making a safe landing. This gallant officer afterward died of his wounds.” (Congressional citation.) Clair died in a German hospital on October 4, 1918, after being wounded in the mid-air battle near Doulcon, France. He was also awarded the Croix de Guerre for his actions. Originally buried in Stenay, France, he was later reinterred at Meuse-Argonne Cemetery. (bit.ly/uw_kinney)

For extraordinary heroism in battle, First Lieutenant Clair Arthur Rawson Kinney, of the 49th Aero Squadron, United States Army Air Service, was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. “With a patrol of six other machines Lieutenant Kinney attacked 17 enemy planes, (Fokker type). Diving into the midst of the enemy formation he fired into one of the German planes, and pursued it until it crashed to the ground, though he was wounded by another Fokker, which attacked him from the rear. After maneuvering to escape his pursuer, Lieutenant Kinney immediately attacked another enemy plane directly in front of him, and forced it to the ground. In so doing he was fired upon from behind by another Fokker, several bullets striking him in the body and another setting fire to his gas tank. He succeeded in making a safe landing. This gallant officer afterward died of his wounds.” (Congressional citation.) Clair died in a German hospital on October 4, 1918, after being wounded in the mid-air battle near Doulcon, France. He was also awarded the Croix de Guerre for his actions. Originally buried in Stenay, France, he was later reinterred at Meuse-Argonne Cemetery. (bit.ly/uw_kinney)

Clair was the youngest of Martin Palmer Kinney and his wife, Margaret Mahoney’s four sons. Clair was born in Sioux City, Iowa and raised in Endicott, Washington. Immediately following the declaration of war he enlisted. In May, 1917, he was appointed to the Presidio for the First Officers’ Training School. He unit advanced to front early in fall of 1918. A senior in the College of Fine Arts when he withdrew from the UW, Clair was a member of the Varsity Boat Club and planned to pursue a career in architecture.

Harry B. Leavitt was a first-year law student at the University of Washington when the US entered World War I. A native of Chicago, Harry was one of four children born to Russian immigrants Bernard Leavitt and Anna Towlen. At the time he registered for the draft Harry was working as a clerk with the Standard Oil Company, then located in Seattle’s iconic Alaska Building.

Harry B. Leavitt was a first-year law student at the University of Washington when the US entered World War I. A native of Chicago, Harry was one of four children born to Russian immigrants Bernard Leavitt and Anna Towlen. At the time he registered for the draft Harry was working as a clerk with the Standard Oil Company, then located in Seattle’s iconic Alaska Building.

Harry served as a Sergeant in the Quartermaster Corps – the Army’s logistical unit responsible for organizing equipment and materials in the field and providing support for soldiers – which was instrumental in getting the newly-formed Camp Lewis up and running.

Half of the UW’s casualties died of disease rather than injuries or combat, including Harry. Unlike most of his comrades, however, who died of infectious disease, Harry died of cranial hemorrhage due to a brain tumor at Seattle’s Providence Hospital on 28 March 1918. (bit.ly/uw_leavitt) Harry was an active member of the Young Men’s Hebrew Association.

Captain Wilfred Lewis served as a supply officer with Quartermaster Corps of the 91st Division in France, working tirelessly during the Battle of the Argonne, traveling continuously with little opportunity for rest. The hardship he endured may have contributed to his death from pneumonia on February 10, 1919, at a hospital at La Ferte Bernard, twenty-seven miles southeast of Paris. His older brother, Major John Lewis, lost his life with the Canadians at the Somme in 1916 and Wilfred was resolved to enlist, as well. “He enlisted at the declaration of war but was held in construction work at Camp Lewis until made supply officer with the 91st.” (TYEE, 1919, pg. 37.)

Captain Wilfred Lewis served as a supply officer with Quartermaster Corps of the 91st Division in France, working tirelessly during the Battle of the Argonne, traveling continuously with little opportunity for rest. The hardship he endured may have contributed to his death from pneumonia on February 10, 1919, at a hospital at La Ferte Bernard, twenty-seven miles southeast of Paris. His older brother, Major John Lewis, lost his life with the Canadians at the Somme in 1916 and Wilfred was resolved to enlist, as well. “He enlisted at the declaration of war but was held in construction work at Camp Lewis until made supply officer with the 91st.” (TYEE, 1919, pg. 37.)

The youngest of five children born to John Simon Lewis and Harriet Richards Boyle, Wilfred was a native of Dubuque, Iowa. He was a graduate of Dubuque High School and attended Beloit College for two years before graduating from the University of Illinois in 1907 with a degree in Civil Engineering. Following his graduation from Illinois, Wilfred moved to Seattle, where he was engaged in construction and regrade work. He then served for four years as general secretary for the campus YMCA before becoming the Superintendent of Buildings and Grounds at the University of Washington. He was the UW’s only staff casualty. He was actively engaged in the Boys’ club and served as a faculty advisor to Phi Kappa Psi Fraternity, having been a member at Illinois. A talented tenor, he headlined UW Glee Club concerts throughout the state.

Wilfred was married to Caroyln Gray Tripple on January 21, 1913, in Seattle. They were the parents of a young son, John Simon Lewis, at the time Wilfred was dispatched to France in July, 1918. A daughter, Mary Carolyn, was born posthumously in April, 1919. Wilfred is buried at Oise-Aisne American Cemetery in France. (bit.ly/uw_lewis) A cenotaph at Linwood Cemetery in Dubuque, Iowa, is dedicated to the memory of both Wilfred and his brother, John. (bit.ly/uw_lewis2)

Captain Charles Arthur Lindbery died of pneumonia and complications of spinal meningitis at Camp Lee, Virginia, on 27 May 1918. Just a few days prior to his death he had broken his left wrist while helping his men pull a truck out of a mud hole saving the life of one of his men. The injury prevented him from going overseas with his unit. Charles was an 1896 graduate of Whatcom High School and received a liberal arts degree from the University of Washington in 1901. While at the UW, Charles served as Captain of Company “A” of the University Cadets and was a member of the Mandolin and Guitar Club. A former commander of Company M, 2nd Washington Infantry, Charles served as a captain with the 601st Engineers where he was responsible for 900 men. A promotion to Major was pending at the time of his death.

Captain Charles Arthur Lindbery died of pneumonia and complications of spinal meningitis at Camp Lee, Virginia, on 27 May 1918. Just a few days prior to his death he had broken his left wrist while helping his men pull a truck out of a mud hole saving the life of one of his men. The injury prevented him from going overseas with his unit. Charles was an 1896 graduate of Whatcom High School and received a liberal arts degree from the University of Washington in 1901. While at the UW, Charles served as Captain of Company “A” of the University Cadets and was a member of the Mandolin and Guitar Club. A former commander of Company M, 2nd Washington Infantry, Charles served as a captain with the 601st Engineers where he was responsible for 900 men. A promotion to Major was pending at the time of his death.

At the time of his enlistment, Charles was serving as the County Engineer for Whatcom County and he was active in the Washington State Association of County Engineers. His parents Albert Lindbery and Ida Sohyberg were both Swedish immigrants living in Albany, New York, when Charles was born. In 1909 Charles was united in marriage with Ada Lenora Wilson. Tragedy struck the young couple in 1914 when Ada and their infant son, Charles Jr., both died shortly after his birth. In 1916 Charles married secondly Charlotte Louise Larson who survived him. Charles’ body was returned to Washington and he was laid to rest at the Wright Crematory and Columbarium in Seattle. (bit.ly/uw_lindbery)

“The influenza epidemic gilded another star on the University’s great service flag when it carried off John Henry Martin ‘16, Sergeant in Ambulance Company 11. He was stationed with his unit at Camp Fremont, California, at the time of the scourge and died there on October 17, 1918.” (TYEE, 1919, pg. 45.) He is buried in Spokane, at Greenwood Memorial Terrace. (bit.ly/uw_martin)

“The influenza epidemic gilded another star on the University’s great service flag when it carried off John Henry Martin ‘16, Sergeant in Ambulance Company 11. He was stationed with his unit at Camp Fremont, California, at the time of the scourge and died there on October 17, 1918.” (TYEE, 1919, pg. 45.) He is buried in Spokane, at Greenwood Memorial Terrace. (bit.ly/uw_martin)

Born in Ritzville, John was the oldest of Benjamin Martin and Mattie Eliza Greene’s three children. He studied at Whitman College — where he was known as Tubby — before enrolling at the UW. John graduated with a degree in chemistry in 1916 and was a member of Alpha Tau Omega Fraternity. After graduating he worked as a chemist for the International Cement Company near Spokane.

John enlisted on May 19, 1917, “among the first from the University to answer the martial call.” (Seattle Post-Intelligencer, October 20, 1918.) On May 24, 1917 — shortly before he departed for training in California — he was married to Whitman classmate Elsie Virginia Wilson. Elsie never remarried and pursued a career as a dietitian, eventually becoming a Professor of Dietetics and an original faculty member at Duke University’s School of Nursing.

As the battle in the Argonne Forest raged into its fourth day, and after numerous casualties, Second Lieutenant Adelbert Durkee McCleverty was appointed to lead his battalion’s charge against the village of Gesnes. The battalion was successful but McCleverty was wounded in the process and died on the battlefield on September 29, 1918. He is buried at Meuse-Argonne Cemetery in France. (bit.ly/uw_mccleverty) After serving for four years in the 2nd Regiment of Washington’s National Guard, Adelbert attended officers training camp at the Presidio and received a commission. He was assigned to Company G, 362nd Infantry, part of the 91st Infantry “Wild West” Division. Highly regarded by his men, McCleverty was described as “modest and unassuming” and a “natural leader” by Colin Dyment in his series about the actions of the 91st. (Morning Oregonian, 8 May 1919, pg. 7.) Dyment goes on to quote Adelbert’s commander “he inspired confidence by his goodness rather than by his aggressiveness.”

As the battle in the Argonne Forest raged into its fourth day, and after numerous casualties, Second Lieutenant Adelbert Durkee McCleverty was appointed to lead his battalion’s charge against the village of Gesnes. The battalion was successful but McCleverty was wounded in the process and died on the battlefield on September 29, 1918. He is buried at Meuse-Argonne Cemetery in France. (bit.ly/uw_mccleverty) After serving for four years in the 2nd Regiment of Washington’s National Guard, Adelbert attended officers training camp at the Presidio and received a commission. He was assigned to Company G, 362nd Infantry, part of the 91st Infantry “Wild West” Division. Highly regarded by his men, McCleverty was described as “modest and unassuming” and a “natural leader” by Colin Dyment in his series about the actions of the 91st. (Morning Oregonian, 8 May 1919, pg. 7.) Dyment goes on to quote Adelbert’s commander “he inspired confidence by his goodness rather than by his aggressiveness.”

The oldest of three children born to Judge Joseph D. McCleverty and his wife, Mary Richardson, Adelbert was born and raised in Fort Scott, Kansas. He graduated from Fort Scott High School and then attended the University of Kansas. Following the death of his father, Mary and her children moved to Seattle where Adelbert decided to follow in his father’s footsteps and attend law school. He graduated with a law degree from the University of Washington in 1911. He was a member of Phi Gamma Delta Fraternity at Kansas and the UW. Adelbert married Phebe Mae Pierce on May 18, 1915, in Seattle. Following Adelbert’s enlistment she took his place in her husband’s law office. She went on to study law and was admitted to the bar in 1920, when she took over her husband’s practice.

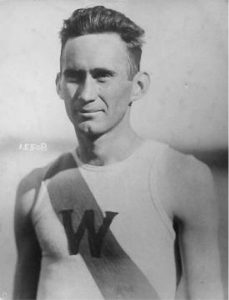

First Lieutenant William Joseph Alexander MacDonald was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for extraordinary heroism in action while serving with 167th Infantry Regiment, 42nd Division, near Landres-et-St. Georges, France on October 14, 1918. When the platoon commanded by Lt. MacDonald began the attack, it encountered a tremendously heavy artillery and machine-gun fire. Realizing the difficult and hazardous position his men were in, and with utter disregard of his own personal safety, Bill valorously led the platoon forward and attained the objective. In the performance of this brave act Lt. MacDonald so encouraged his men that they continued to carry on after he had made the supreme sacrifice. (Congressional Commendation.)

First Lieutenant William Joseph Alexander MacDonald was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for extraordinary heroism in action while serving with 167th Infantry Regiment, 42nd Division, near Landres-et-St. Georges, France on October 14, 1918. When the platoon commanded by Lt. MacDonald began the attack, it encountered a tremendously heavy artillery and machine-gun fire. Realizing the difficult and hazardous position his men were in, and with utter disregard of his own personal safety, Bill valorously led the platoon forward and attained the objective. In the performance of this brave act Lt. MacDonald so encouraged his men that they continued to carry on after he had made the supreme sacrifice. (Congressional Commendation.)

Bill was with his regiment in the Argonne and was killed on October 14th while attacking Cote de Chatillon. Early in the attack he received a bad shrapnel wound in the leg, but carried on until his platoon was established, Bill started to crawl back to a dressing station. He had gone but a short distance when a shell fell near him and he was instantly killed. Three days later the chaplain of his regiment found his body and he was buried on the north side of Cote de Chatillon with three of his men who were lying near him.

The only child of Dr. Alexander MacDonald, and his wife, Margaret Anna Forster, Bill was a 1917 graduate of the UW’s law school, a member of Kappa Sigma Fraternity and captain of the track team in 1917. In honor of Bill, a University athletic field was named MacDonald Field “for all time.” (TYEE, 1919, pg. 35.) In addition to his parents, Bill was also survived by his wife, Helen Bain, a fellow UW student, who he married on April 7, 1917. Originally buried in France, Bill was later reinterred in Minnesota. (bit.ly/uw_macdonald)

Lieutenant Frank Everett McNett served with the Dental Corps within the Army’s Medical Department. At the time of his death he was posted to Camp Greenleaf, a medical officer training camp at Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia. He died of pneumonia following influenza in nearby Chattanooga, Tennessee, on December 18, 1918. Frank was one of just three physicians selected to complete a course of study at Columbia University in plastic surgery and reconstruction. Funeral services, with full military honors, were held at the camp.