Harry Bridges at the founding of the Maritime Federation of the Pacific, circa 1935

by Annika Tuohey

“Longshoremen Killed” read the headline in The Voice of the Federation. The August 27, 1936 article detailed the death of Seattle longshoreman John Kreuger, a member of the International Longshoremen’s Association Local 38-79. Attempting to avoid a swinging load, Kreuger took a step backwards and fell thirty feet, hitting his head as he landed. The Voice of the Federation, a weekly newspaper serving the ILA and other west coast maritime unions, attributed the death to “shipowners’ disregard for human life,” citing the death as just one of a mounting list of wrongdoings and grievances in the summer of 1936.[1] Within two months of John Kreuger’s death, the ILA, alongside seven other maritime unions, went on strike for the second time in just two years, demanding improved working conditions, hiring practices, and compensation.

The 1936 Pacific Coast Maritime Workers’ Strike is less known than the violent, flashy maritime strike of 1934. But it was no less important. The 1936 strike paralyzed shipping up and down the west coast, complicating the economic recovery that had been pulling the nation out of the Great Depression. Yet public opinion favored the strikers, and the 99-day strike was almost entirely without violence as employers refrained from hiring strike-breakers and trying to reopen the ports. Victory for the strikers brought better wages and safer working conditions and, equally important, ensured the future of the longshore union, Sailors Union of the Pacific, and five other maritime unions that had won contracts in 1934 but had to defend them only two years later. And news about the rock-solid solidarity of maritime workers on the west coast helped inspire workers and unions across the country. Two months after the start of the Pacific Coast strike, the fledgling United Autoworkers Union would launch the Flint sit down strike that led off the great campaign to unionize the auto and steel industries. Yet the strike also led to a split in the West Coast labor movement, paralleling the coming battle between the unions of the AFL and the new CIO.

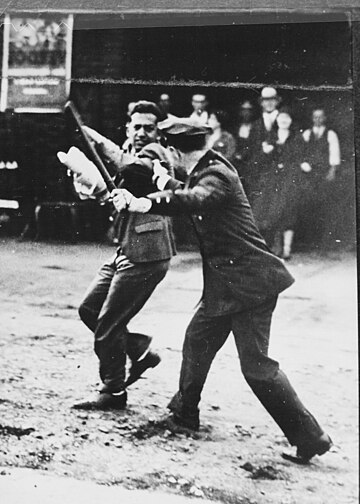

Conflict between a policeman and striker on July 5, 1934, also known as “Bloody Thursday,” during the 1934 West Coast Waterfront Strike.

1934 Strike

An 83-day long waterfront strike in 1934 set the stage for the 1936 confrontation. In 1934, the International Longshoremen’s Association, supported by the Sailors’ Union of the Pacific and the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, organized a coast-wide walk out to protest the unfair hiring practices and working conditions the longshoremen were being subjected to by shipowners. This violent strike came to a climax on July 5, 1934 when two maritime workers were shot dead by San Francisco police and 69 were injured in an altercation with strikebreakers deployed by employers. This day came to be known as “Bloody Thursday” and two weeks later, on July 19, the strike came to an end, as both parties were eager to avoid any additional incidents of violence. Strikers agreed to employers' offer of arbitration, in which a neutral third party would make the final decision regarding the workers’ demands.

On October 12, 1934, the Arbitration Committee came to a conclusion on the awards that would be granted to the striking unions. This strike resulted in the unionization of all port cities along the Pacific Coast, including Everett and Seattle, Washington. Additionally, the Arbitration Committee awarded a number of gains to union members, including higher wages, shorter working hours, and joint control of their hiring halls with employers. These agreements included set pay of $0.95 per hour and $1.40 per hour for overtime work, as well as a six-hour workday and thirty-hour work week.[2] Upon final approval, these awards were set to expire in two years, on September 30, 1936.[3]

These official gains were not the only notable results of the 1934 strike. New leaders had emerged in the strike and two of them, Harry Bridges and Harry Lundeberg, would become dominant figures in maritime unions in 1936 and for decades to come. Bridges had been working on the San Francisco docks since 1922 and by 1934 had become a key player in the ILA’s Pacific Coast District. Throughout the 83 days of that strike, Bridges acted as a representative of the ILA, serving as a spokesman for them in meetings with employers, the National Labor Relations Board, and the Labor Council.[4] In 1935, a year after the end of the 1934 strike, Harry Bridges was elected president of the San Francisco local of the International Longshoremen’s Association and of the Maritime Federation of the Pacific’s District 2. His leadership continued through the following years, making him an integral part of the 1936 strike.

Harry Bridges, president of the San Francisco Local of the International Longshoremen's Association, president of District II of the Maritime Federation of the Pacific, and founder of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union, circa 1937.

Harry Lundeberg emerged as a leader in the Sailors Union of the Pacific during the 1934 strike when he was elected union “patrolman” for the Seattle district. Born in Norway, he had worked as a merchant seaman since 1918, moving to the US and becoming a citizen around the time that Harry Bridges, born in Australia, had moved to America. The two Harrys would cooperate initially in the Maritime Federation but argue over tactics during the strike and later become bitter enemies.[5]

Maritime Federation of the Pacific

In April of 1935, seven maritime unions of the West Coast joined forces under a single banner: the Maritime Federation of the Pacific. These unions included the International Longshoremen’s Association, Sailors’ Union of the Pacific, Marine Engineers Beneficial Association, American Radio Telegraphists, Marine Firemen, Oilers, Watertenders, and Wipers Association, International Organization of Masters, Mates, and Pilots, and the National Union of Marine Cooks and Stewards. The goal of the MFP was to portray a united front of maritime unions against shipowners in times of disharmony on the docks. Harry Bridges chaired the Maritime Federation’s constitutional committee in hopes of establishing a “Union Labor Party.”[6] The Maritime Federation was divided into four districts; District 1: Puget Sound, District 2: Northern California, District 3: Columbia River, and District 4: Southern California. Due to his influence during its formation and his leading role in the ILA, Harry Bridges was elected the first president of District 2 of the Maritime Federation, as well as a chairman to the Joint Policy Committee, which was formed to speak for the Federation during times of strike. To his disappointment, Bridges failed to gain the votes necessary to be elected president of the Maritime Federation as a whole. That position instead fell to Harry Lundeberg, president of the Sailors’ Union of the Pacific.[7] Despite infighting that occurred between Bridges and Lundeberg, the Maritime Federation was successful in creating a united image for the seven unions during the 1936 strike, which played a major role in avoiding a repeat of the violence seen two years before.

Harry Lundeberg, head of the Sailors’ Union of the Pacific and president of the Maritime Federation of the Pacific.

In 1935 the Maritime Federation created The Voice of the Federation, their official newspaper. The first edition, published on June 14, 1935, read “an injury to one is an injury to all” on its cover page, which emphasized the unity they were attempting to build.[8] For the first year, The Voice of the Federation was used to share stories of shipowners’ wrongdoings. For example, the August 20, 1936 edition included a piece entitled “My Son Starved to Death, Says Stricken Father,” in which the story is told of a maritime worker who was making only $2.00 each week and could not afford to feed himself. The story highlights the unlivable wages that had been fought in 1934 and would be fought again in 1936.[9] The Voice of the Federation continued as an active publication leading up to and throughout the 1936 strike and was utilized to bolster public support for their strike efforts from both the American people and other labor unions.

The Voice of the Federation, October 29, 1936, vol. 2, no. 21.

Preparations

The peace between employers and unions in July of 1934 did not last long, as maritime workers began to seek further gains months before their current agreements expired, and shipowners refused to meet any new demands and thought there might be an opportunity to roll back provisions of the 1934 agreement.[10] The political context contributed to the shipping companies’ calculations. FDR would stand for re-election in November and many newspapers predicted that he would lose, an outcome that would help the shippers. With agreements set to expire at the end of September 1936, the Maritime unions set new demands, expanding upon those won by the International Longshoremen’s Association in 1934. These included preferential employment for union members, overtime payment in the form of cash and not in additional time off, and eight hour work days for ship crew departments, as well as the continuation of all 1934 agreements.[11] The Coast Committee of Shipowners, which had been formed to counter the Maritime Federation, refused to negotiate any changes, and planned for a strike.[12]

The animosity between shipowners and maritime workers left behind from the violent strike of 1934 made it impossible for the two parties to reach any agreements before the awards were set to expire on September 30, 1936. Seeing no simple path forward, unions prepared to strike at midnight if employers refused to meet their demands. A second major strike in just two years was of great concern to President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his administration as they prepared for reelection in just a few months. A waterfront strike would affect not just the maritime industry, but businesses and industries across the nation that relied on shipping in the West Coast. Unlike a manufacturing strike, whose effects would remain primarily within its own industry, a transportation strike would have widespread consequences.[13] As the United States struggled to recover from the Great Depression, there was serious uneasiness within the Roosevelt administration that another major strike would set back the country’s economic recovery.

The Voice of the Federation, December 31, 1936, vol. 2, no. 30.

Hoping to avoid a strike, or at least delay one as long as possible, the Roosevelt administration successfully extended the 1934 agreements until October 15, 1936.[14] This postponement allowed for additional negotiations between employers and unions, as well as government investigations by the Department of Labor and the three-month-old U.S. Maritime Commission. On June 29, 1936, Roosevelt signed the Merchant Marine Act of 1936, which established the Maritime Commission, but didn’t appoint even temporary commissioners until late September of the same year. Labor leaders, including Edward McGrady of the American Federation of Labor and Frances Perkins, the U.S. Secretary of Labor, urged the president to do so in order to gain support and confidence from the growing force of unions.[15] However, the Maritime Commission proved ineffective during the two week extension period, as their full power did not come into effect until October 26, making them incapable of performing full investigations until that date. Harry Bridges, speaking for the Maritime Federation, agreed to extend the agreements once again until the end of October. He hoped that with their full power, investigations by the Maritime Commission on working conditions and wages would work in the Federation’s favor. Shipowners also agreed, hoping that the Maritime Commission could be used to force arbitration upon the unions.[16] Both organizations, however, found themselves disappointed in the ineffectiveness of the Maritime Commission, which was unable to do anything substantial to prevent a strike.

Still, between September 30 and October 30, negotiations and arguments between maritime unions and shipowners took place. As little came of the Maritime Commission’s involvement, employers continued to push for arbitration, which unionists took as a threat to their fundamental rights as workers and refused to agree to. In The Seattle Star, on October 2, 1936, workers explicitly stated that they were “opposed to arbitration of conditions we already enjoy.”[17] The Maritime Federation unions made clear not only to shipowners, but to the American public that they would not accept less than the revisions they demanded. Employers viewed this as workers being hostile and refusing to attempt to reach agreements, making no efforts at peace.[18] As unionists fought for their basic rights, employers felt their own fundamental rights, such as the ability to pick their own employees and for their employees to work, were being challenged.[19] They promised to turn to hiring off the docks if workers continued to refuse arbitration, however, their threats did not deter the unions from standing behind their demands. As hopes for a peaceful resolution faded for both sides, it became clear to the unions of the Maritime Federation that a strike was the only path forward to achieve substantial change.

Before the strike began, fractures within the Maritime Federation were forming, specifically between Harry Bridges and Harry Lundeberg. Despite the Federation’s adoption of joint action policy for its seven unions, differences between the two had become apparent in 1935 due to Bridges’s ties to the Communist Party, which disagreed with many of Lundeberg’s ideas and policies.[20] During the MFP’s formation, Bridges fought for Resolution 47, which would have narrowly defined job action, which refers to temporary protests or quickie strikes to demonstrate dissatisfaction with working conditions to employers. This proposal would have set a very strict interpretation of what types of job action would be allowed for unions within the Maritime Federation, ensuring that any form of protest that impacted other unions would not be permitted. As Resolution 47 was primarily targeted towards the SUP, Lundeberg rewrote the proposition to include much broader terms of job action, that would have allowed for labor protests that harmed or endangered the agreements of other unions.[21] Despite Lundeberg’s success with his version of Resolution 47, many people believed him to be a puppet for Harry Bridges to achieve his goals, which only contributed further to the dislike between the two. Disagreements such as these and their continued different approaches to the upcoming strike led these fissures to only grow throughout the following three months.

At 12:00 AM on October 30, 1936, maritime workers across the Pacific Coast, unwilling to shelve their demands any longer, struck. The following day port cities from southern California to northern Washington were abandoned and the shipping industry of the West Coast came to a halt, as 37,000 workers walked off the docks. Things remained this way for ninety-nine straight days, as maritime laborers from all seven unions within the Maritime Federation refused to work until granted all demands from employers. As explained by The Seattle Star on October 30, 1936, this strike would involve 12,000 ships along the coast, responsible for carrying 30,000 tons of cargo each year and creating a $250,000,000 industry.[22] As the strike got under way, the Roosevelt administration feared the potential development of sympathy strikes in other parts of the country. The Voice of the Federation’s November 5 edition was headlined “Maritime Workers Strike Spreads Eastward: Atlantic and Gulf Coast Unions Stop Ships.”[23] This expansion heightened the significance of the strike, as their reach and economic impacts increased. While it may have appeared to be a more dramatized version of the 1934 strike, there is one major, notable difference between the two lay in the tactics used by both shipowners and unions.

The Seattle Star, December 14, 1936, vol. 38, no. 249.

War of Words

Each union of the Maritime Federation of the Pacific had agreed to negotiate with employers individually, building their own separate contracts and putting them on their own timelines. In the early weeks of the strike, shipowners were not eager to begin negotiations, as they were hoping to outlast the unions and maintain control of the agreements. However, as the unions found themselves with high levels of support from the American public, they were in no rush to concede to employers. Despite occurring just two years later, this maritime strike was drastically different from that of 1934. The 1934 strike brought violence and fear to the Pacific Coast shores, while the 1936 strike ended without a single incident of violence, with no strikebreakers and no deaths or injuries. This can largely be attributed to the mass newspaper coverage of the strike. As both parties spread their message through the press, the strike turned into a “war of words.”[24]

The Seattle Star’s edition on October 30, 1936 contained a segment titled “What Both Sides Say,” in which adjacent columns offered statements on the strike from both the Maritime Federation and the Coast Committee of Shipowners.[25] On one side, F.M. Kelley, secretary-treasurer of the MFP, claimed that “every effort has been made by the unions to avoid a tie-up of shipping,” while on the other hand, Thomas G. Plant, a chairman of the Coast Committee, wrote that “shipowners did everything possible to try to achieve a peaceful settlement.”[26] By building a single space for both parties to give their opinions, The Seattle Star created an environment for the “war of words” to flourish and become the main outlet of the strike. Additionally, mass meetings were held in major cities along the coast, including Seattle and Oakland, which included speeches by union leaders and public officials, as well as debates between unions and employers. According to the San Francisco Chronicle, due to its seemingly nonviolent and civil nature, this strike would “mark a new era in the settlement of such affairs.”[27]

The Voice of the Federation also played a major role in spreading awareness of the maritime unions’ efforts and garnering support for their cause. Throughout the strike, unions relied on this publication to convey the image of a single united group of maritime workers against the unethical practices of their employers. For example, in the November 19, 1936 edition the newspaper claimed that the “solidarity of unions strengthen lines as strike extends into third week,” promoting their unity against employers as both sides avoided negotiations.[28] As the strike continued, on December 31, 1936, The Voice of the Federation used the tagline “owners’ stand blocks way to marine peace,” as they wrote of the employers’ stubbornness to not consider anything but arbitration.[29] The Voice of the Federation portrayed to both maritime workers and the American public the unfair treatment and refusal to cooperate coming from employers.

The Seattle Star, October 30, 1936, vol. 38, no. 212.

Across the country the press was paying more attention and showing more sympathy towards workers and unions than perhaps ever before. Labor was on the march in 1936, recording 2,172 strikes that year, the largest number since 1921.[30] Most major newspapers were owned by conservative publishers, but after four years of Roosevelt’s New Deal and a year after the passage of the Wagner National Labor Relations Act (1935), newspapers were responding to the widespread public support for labor with even handed news coverage. That was true in Seattle, where the newly formed American Newspaper Guild had just won a strike against the Hearst-owned Seattle Post-Intelligencer and where the Seattle Star (part of the Scripps-Howard chain) was rebuilding its reputation for supporting unions. In his account of the strike, Communist Party activist William Schneiderman described the importance of public opinion and media coverage noting that it created the image of a united front and “almost caused a break in the shipowners.”[31] Even “the capitalist press,” he wrote, referred to the maritime protest as a “stream lined strike,” referencing their organization and discipline that would inspire labor movements across the country.[32] Additionally, as the federal government strongly did not want another strike, they certainly did not want another violent strike. Shipowners faced pressure from all sides, including other unions, the public, the press, and the federal government, to remain civil during the strike, which likely prevented the use of strikebreakers, which could have resulted in a second Bloody Thursday.

Harry versus Harry

Despite the united front the

Maritime Federation may have portrayed, infighting quickly began between the

different unions. Many of these arguments occurred between Harry Bridges and

Harry Lundeberg, as they severely disagreed on how to handle the strike and negotiations with employers. Shipowners were not blind to these

rifts between the leaders of the International Longshoremen’s Association and

the Sailors’ Union of the Pacific and attempted to capitalize on them and

divide the Federation even further.[33] However, despite employers’

best efforts, the ILA refused to accept any agreements with employers unless

the demands of the SUP were also met.

Lundeberg, on the other hand, appeared

less dedicated to the image of unity and reached tentative agreements with the

Coast Committee for the Shipowners, before five of the unions of the MFP,

including the International Longshoremen’s Association, had even met with

employers. In December of 1936, after meeting with only the Sailors’ Union of

the Pacific and the Marine Firemen, Oilers, Watertenders, and Wipers

Association, shipowners took to the newspapers, claiming the strike had ended.

On December 14, the headline of The

Seattle Star read “peace is believed near in ship strike” and an article

quoted Lundeberg in saying that “the most important issues which caused sailors

to go out were conciliated.”[34] These agreements for the Sailors’ Union included an increase in wages to $72.50

per month, an increase in overtime pay to $0.70 per hour, and cash pay for

overtime. Alaskan workers would be receiving their own separate wage increases

of $82.50 per month and $0.80 per hour for overtime.[35] Lundeberg called for a

referendum vote within the SUP without offering any modifications and, while

these agreements may have favored the sailors, they also would have made it

virtually impossible for other unions to refuse agreements or request modifications,

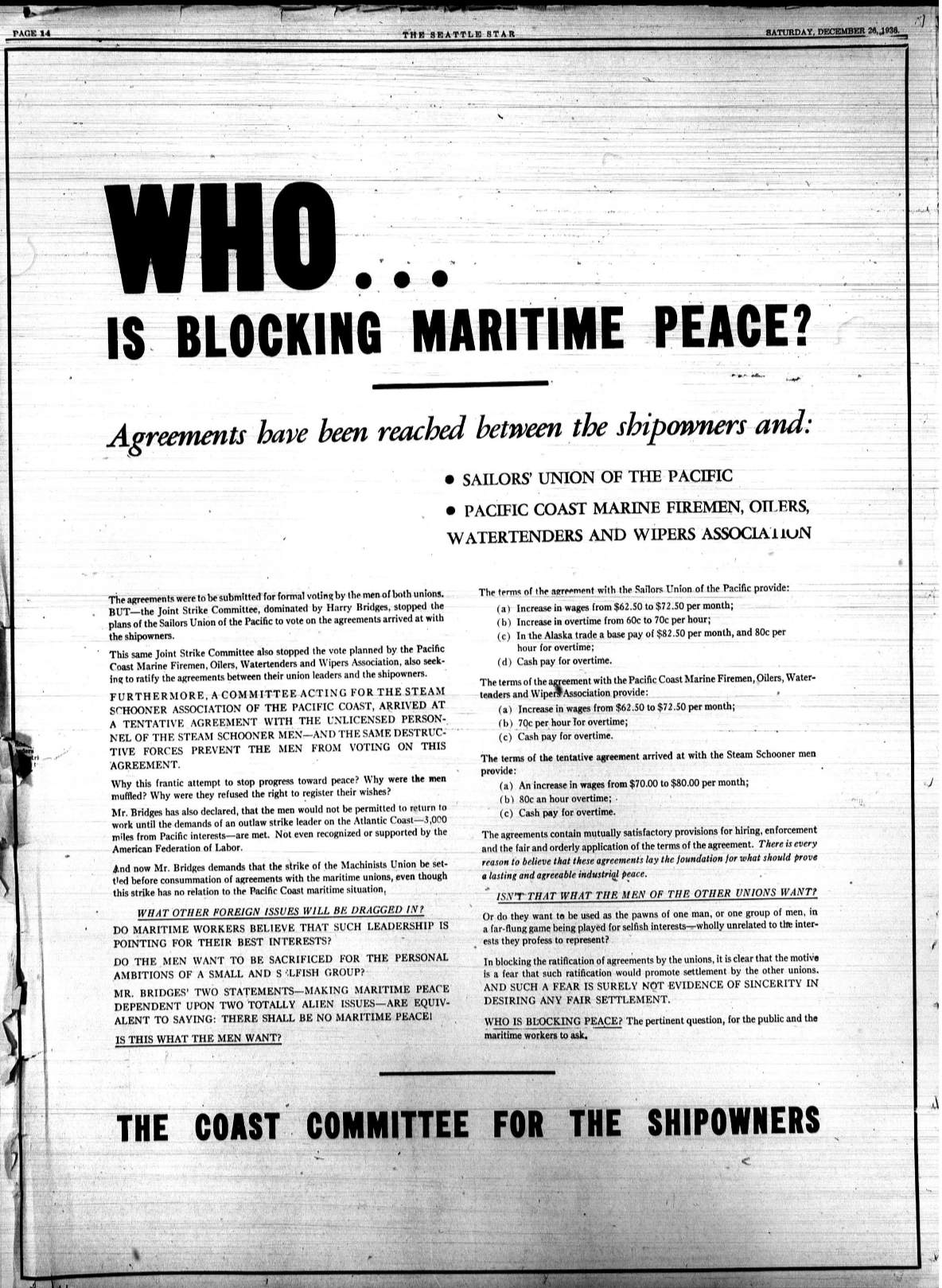

without being “accused of blocking peace.”[36] In a one pager found in the

December 16 edition of The Seattle Star,

the Coast Committee for the Shipowners blamed Harry Bridges and the entire

Joint Policy Committee for their “frantic attempt to stop progress toward

peace,” as they urged the SUP and MFOW to not reach firm agreements before the

rest of the Maritime Federation met with employers.[37] Ultimately, both unions

rejected the agreements for these reasons, which was a victory for the ILA,

however, the divide between Lundeberg and Bridges had already been formed and

would only continue to grow through the end of the strike.

The Voice of the Federation, August 12, 1937, vol. 3, no. 10.

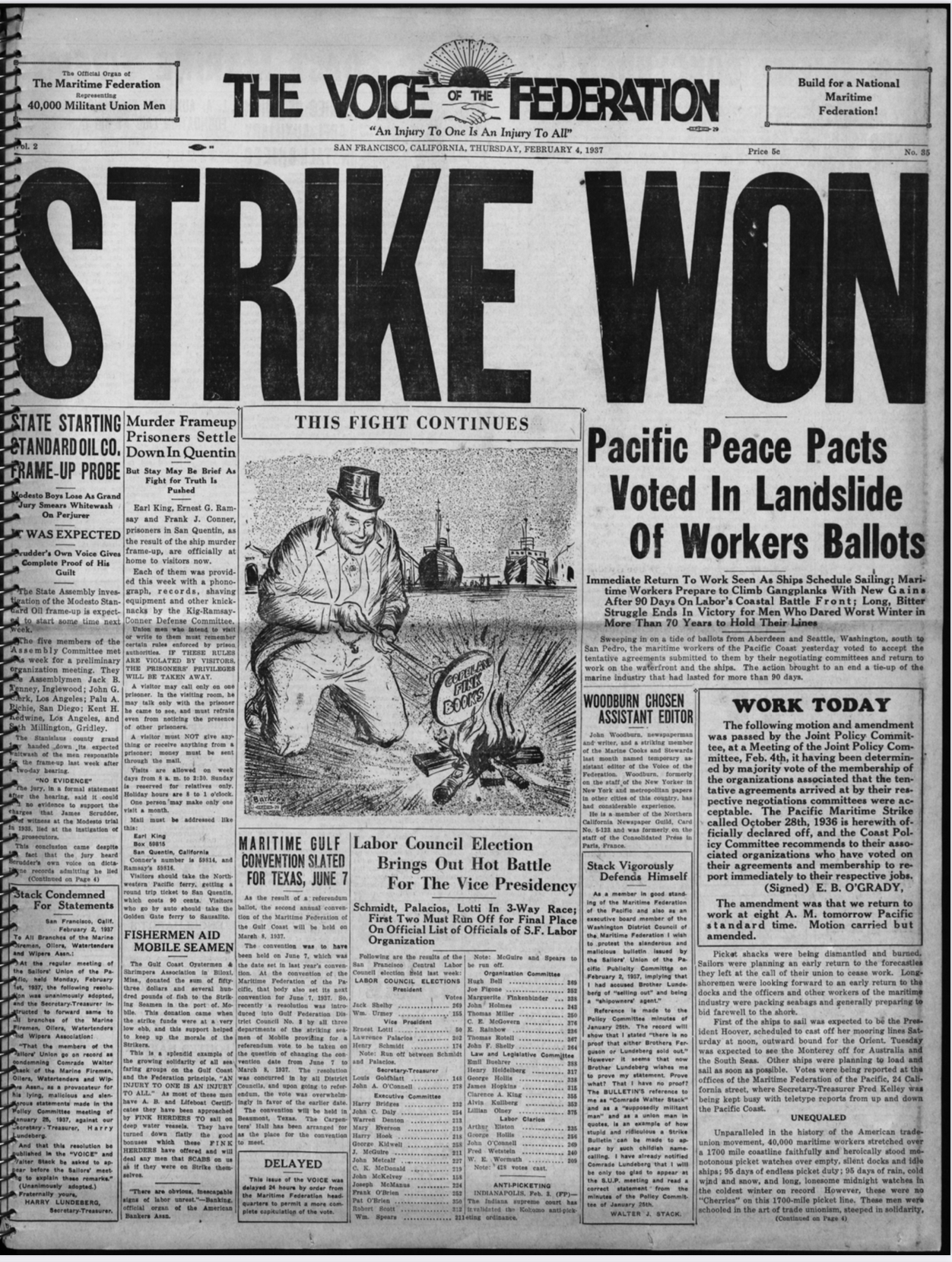

Regardless, in early January of 1937 all maritime unions were finally in active negotiations with shipowners and by the middle of the month the entire Maritime Federation had reached tentative agreements with employers. During their first negotiation meeting on January 5, 1937 the International Longshoremen’s Association called for the continuation of 1934 agreements with the addition of wage increases, at $1.00 per hour and $1.50 per hour for overtime, and preferential employment, while employers argued against any additions.[38] Throughout the rest of the month neither workers nor shipowners budged on their proposals, until employers finally gave in and made a number of compromises, including preferential employment. Eager to bring the strike to an end, Harry Bridges called for the Joint Policy Committee to agree to their demands or to arbitration by their meeting on January 29, which was quickly approved by a unanimous vote. Within the next few days, all seven unions of the Maritime Federation ratified their own agreements with shipowners and on February 4, 1937 the Joint Policy Committee voted to end the strike at 8:00 AM the following morning.[39] That same day The Voice of the Federation published an edition, headlined “STRIKE WON,” which outlined the awards made for each union and highlighted that their victory could be attributed to their “heroism, sacrifice, and unity.”[40]

Victory

After ninety-nine long days the 1936 strike came to an end and major gains were won by the unions of the Maritime Federation. The International Longshoremen’s Association, in particular, maintained joint control of their hiring hall, six-hour workdays, and a set wage of $0.95 per hour and $1.40 per hour for overtime. Additionally, the longshoremen won preferential employment, ensuring job opportunity priority for union members. Safety on the docks improved as proper safety gear was provided for workers and a safety code, which includes clearly defined job expectations, would be adopted by both the ILA and the Waterfront Employers’ Associations. Lastly, a Labor Relations Committee was established at each port along the Pacific Coast and was responsible for managing and resolving conflicts between employers and employees.[41] Not only did these agreements maintain the awards won in 1934, but they advanced the longshoremen’s control of the ports. Equally important gains were won for the other maritime unions, such as increased wages for the Marine Firemen, Oilers, Watertenders, and Wipers Association and days off on federal holidays for the Sailors’ Union of the Pacific.

Breakup

In spite of the collective gains made by the maritime unions, the 1936 strike left the Maritime Federation of the Pacific in shambles. In the February 4, 1937 edition of The Voice of the Federation, Harry Bridges claimed that the “Maritime Federation emerges from the long struggle much stronger than when it began,” however this was quickly disproved in the months to follow.[42] Following the strike, the Pacific Coast District of the International Longshoremen’s Association began campaigning for industrial unionism alongside the Committee for the Industrial Organization. The leaders of American Federation of Labor condemned the strategy of industrial unionism and moved to oust the CIO unions, which under the leadership of the United Mineworkers President John L. Lewis, promptly launched the Congress of Industrial Organizations, repurposing the CIO acronym. Harry Bridges supported the movement of industrial unionism and was determined that the ILA locals on the Pacific Coast should join the new organization.

In August of 1937, Harry Bridges disassociated the Longshore Local No. 38-79 from the International Longshoremen’s Association and the American Federation of Labor in order to affiliate with the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO).[43] Soon after, the PCD-ILA as a whole held a referendum vote and the entire coastal sector disaffiliated from the national ILA. With this came the division of the International Longshoremen’s Association, as Bridges turned the Pacific Coast District into the new International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU). The ILWU combined the longshoremen and the warehousemen that fought alongside them in the 1936 strike. Harry Bridges explained that the longshoremen’s union was “not going to stay on the waterfront” but rather was “going inland.”[44] By joining forces with warehousemen, the longshoremen’s union was able to gain greater control of multiple aspects of the transportation process, including shipping, storing, and selling.

Map of the ILWU Coast Longshore Division, including all 30 locals.

The 1936 Pacific Coast Maritime Workers’ Strike was a pivotal moment in American labor history and a critical step towards securing fair treatment for workers. Unlike the prior 1934 West Coast Waterfront Strike, which was marked by acts of violence and the deadly Bloody Thursday, the 1936 strike was surprisingly nonviolent, and rather both parties relied on the media to make their cases to the public and the Roosevelt administration. After a 99-day struggle, maritime unions walked away from the strike with a number of gains, including preferential employment, safer working conditions, and the establishment of a Labor Relations Committee at each port.

But without a doubt the most important result of the 1936 strike was the creation of the ILWU. For nearly ninety years that union has maintained the solidarity and reputation that Harry Bridges tried to instill from the beginning. Today the ILWU represents approximately 42,000 members divided into over sixty local unions located in Alaska, Washington, Oregon, California, and Hawaii. A model of democratic unionism, it continues to win the best contracts and conditions for its members, while proclaiming and acting on a commitment to progressive values and social change. Its website explains that commitment: “The history of the ILWU, the record of its origins and traditions, is about workers who built a union that is democratic, militant and dedicated to the idea that solidarity with other workers and other unions is the key to achieving economic security and a peaceful world.” [45]

©Annika Tuohey, 2025

[1] The Voice of the Federation, August 27, 1936, vol. 2, no. 12.

[2] Cherny, Robert W. Harry Bridges: Labor Radical, Labor Legend. 1st ed. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2023, 143.

[3] Labor Archives of Washington, curator, and curator Labor Archives of Washington. International Longshore and Warehouse Union, Local 19 (Seattle) Records., 1918.

[4] Cherny, Harry Bridges, 128.

[5] Cherny, Harry Bridges, 111, 121.

[6] Cherny, Harry Bridges, 148.

[7] Cherny, Harry Bridges, 149.

[8] The Voice of the Federation, June 14, 1935, vol. 1, no. 1.

[9] The Voice of the Federation, August 20, 1936, vol. 2, no. 11.

[10] Schneiderman, William. The Pacific Coast Maritime Strike. San Francisco, Calif: Western Worker Publishers, 1937, 7.

[11] International Longshoremen’s Association. Local -., and International Longshoremen’s Association. Local -. The Maritime Crisis: What It Is and What It Isn’t. 2nd ed. San Francisco: International Longshoremen’s Association Local 38-79, 1936, 7.

[12] Safford, Jeffrey J. “The Pacific Coast Maritime Strike of 1936: Another View.” Pacific Historical Review 77, no. 4 (2008): 585–615. doi:10.1525/phr.2008.77.4.585, 587.

[13] Safford, Jeffrey J. “The Pacific Coast Maritime Strike of 1936: Another View.” Pacific Historical Review 77, no. 4 (2008): 585–615. doi:10.1525/phr.2008.77.4.585, 593.

[14] Safford, Jeffrey J. “The Pacific Coast Maritime Strike of 1936: Another View.” Pacific Historical Review 77, no. 4 (2008): 585–615. doi:10.1525/phr.2008.77.4.585, 588.

[15] Safford, Jeffrey J. “The Pacific Coast Maritime Strike of 1936: Another View.” Pacific Historical Review 77, no. 4 (2008): 585–615. doi:10.1525/phr.2008.77.4.585, 590.

[16] The Voice of the Federation, November 19, 1936, vol. 2, no. 24.

[17] The Seattle Star, October 2, 1936, vol. 38, no. 188.

[18] Coast Committee for the Shipowners., and Coast Committee for the Shipowners. The Pacific Maritime Labor Crisis: On October 15th, 1936, All Present Awards and Agreements Will Expire. San Francisco: Coast Committee for the Shipowners, 1936.

[19] Harrison, Gregory A, Coast Committee for the Shipowners., United States. Maritime Commission., Coast Committee for the Shipowners., and United States. Maritime Commission. Maritime Strikes on the Pacific Coast. A Factual Account of Events Leading to the 1936 Strike of Marine and Longshore Unions. San Francisco: Waterfront Employers Association, 1936, 29.

[20] Schneiderman, William. The Pacific Coast Maritime Strike. San Francisco, Calif: Western Worker Publishers, 1937, 11.

[21] Cherny, Harry Bridges, 155.

[22] The Seattle Star, October 30, 1936, vol. 38, no. 212.

[23] The Voice of the Federation, November 5, 1936, vol. 2, no. 22.

[24] Cherny, Harry Bridges, 169.

[25] The Seattle Star, October 30, 1936, vol. 38, no. 212.

[26] The Seattle Star, October 30, 1936, vol. 38, no. 212.

[27] Cherny, Harry Bridges, 169.

[28] The Voice of the Federation, November 19, 1936, vol. 2, no. 24.

[29] The Voice of the Federation, December 31, 1936, vol. 2, no. 30.

[30] Bureau of Labor Statistics and Florence Peterson, Review of Strikes in 1936 § (1937), 1.

[31] Schneiderman, William. The Pacific Coast Maritime Strike. San Francisco, Calif: Western Worker Publishers, 1937, 8.

[32] Schneiderman, William. The Pacific Coast Maritime Strike. San Francisco, Calif: Western Worker Publishers, 1937, 8.

[33] Schneiderman, William. The Pacific Coast Maritime Strike. San Francisco, Calif: Western Worker Publishers, 1937, 7.

[34] The Seattle Star, December 14, 1936, vol. 38, no. 249.

[35] The Seattle Star, December 16, 1936, vol. 38, no. 251.

[36] Schneiderman, William. The Pacific Coast Maritime Strike. San Francisco, Calif: Western Worker Publishers, 1937, 16.

[37] The Seattle Star, December 16, 1936, vol. 38, no. 251.

[38] Cherny, Harry Bridges, 173.

[39] Cherny, Harry Bridges, 174.

[40] The Voice of the Federation, February 4, 1937, vol. 2, no. 35.

[41] The Voice of the Federation, February 4, 1937, vol. 2, no. 35.

[42] The Voice of the Federation, February 4, 1937, vol. 2, no. 35.

[43] The Voice of the Federation, August 12, 1937, vol. 3, no. 10.

[44] Bonthius, Andrew, “Origins of the International Longshoremen’s and Warehousemen’s Union,” Southern California Quarterly 59, no. 4 (1977): 379–426, 409.

[45] “The ILWU Story,” ILWU, June 15, 2023, https://www.ilwu.org/history/the-ilwu-story/.