Fishing has been a way of life on the West Coast for thousands of years. Coastal Native American tribes built their societies around fish, particularly the iconic salmon. More than just a food source, fishing for many of the First Nations infused every aspect of life and culture. Anglo- Americans introduced a more instrumental way of understanding natural resources and property rights as colonization began in the 1840s. Treaties guaranteed access to ancestral fishing grounds, but in practice these areas were a target of conquest and exclusion.

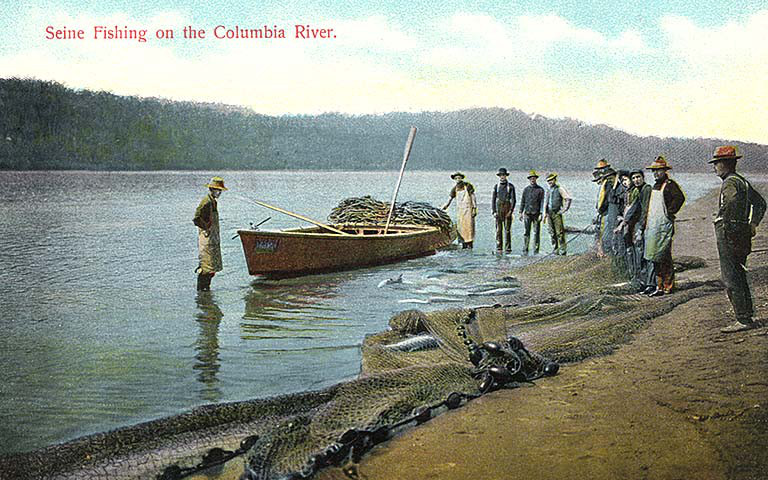

Canning, an industrial mass-production approach to fishing, first appeared in 1864 on the Sacramento River. The emerging technology, developed roughly four decades earlier for lobster and oysters on the East Coast, used an assembly-line process to cut up fish, place them inside metal containers and pressure-cook the product for consumer sale. In doing so, the age old problems of spoilage and preservation were bypassed. Canning abetted a rapacious attitude toward nature and within two years a need for evermore salmon led cannery owners to expanded northward into the plentiful Columbia River. Fishermen followed the canneries, first migrating seasonally from San Francisco to the Sacramento River, and then travelling seasonally from California to Oregon. Business boomed on the Columbia and a community of resident fishermen was established. By 1874, there were thirteen canneries, 600 fishermen and 2,000 cannery workers, numbers which would double a decade later.

Section Highlights

History: "The International Fishermen and Allied Workers of America: Organizing Precarious Workers in the CIO Era," a five-chapter illustrated report by Leo Baunach.

Photos: A selection from the UW Digital Collections

Links to the finding aids of the ILWU local 3 Fishermen's papers and the Laura Korsnes papers at the University of Washington library Special Collections.

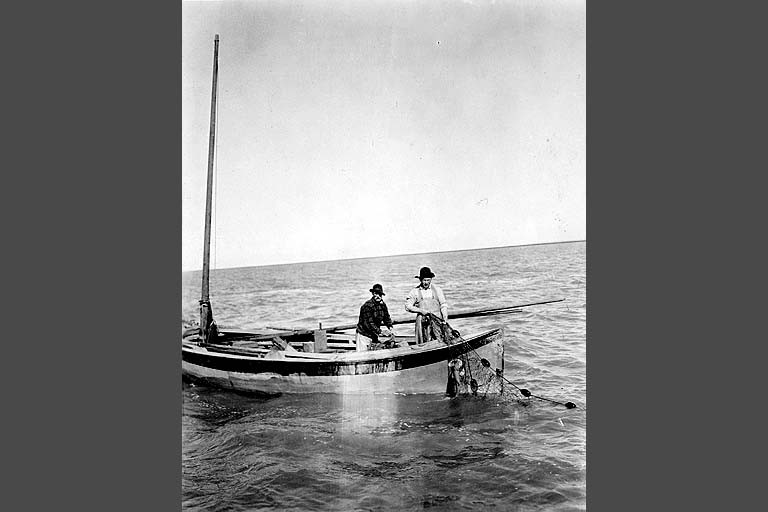

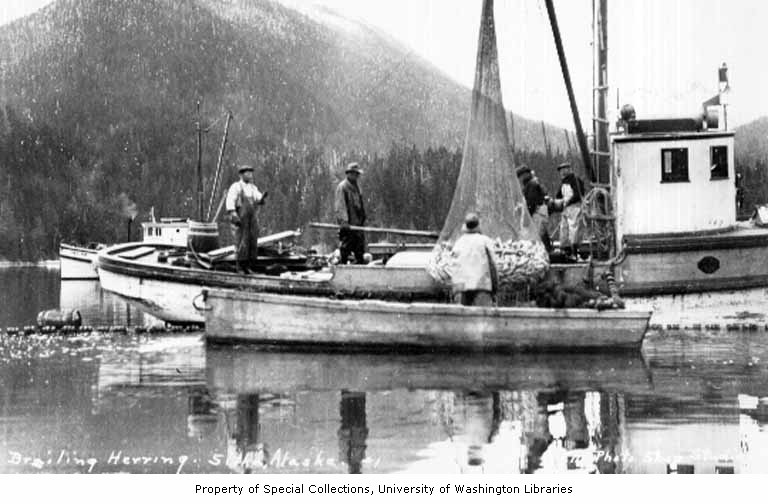

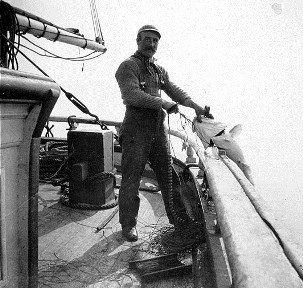

Scandinavian and Finnish immigrants dominated fishing in these early decades. Using small sail boats, they faced enormous risks. Scores died every season. A massive storm in 1880 brought that year’s death toll to over 250. Before the anti-Chinese driving out campaigns exploded in the 1880s, Chinese immigrants did the unpleasant work of processing and canning the salmon.

White fishermen organized the first unions partly out of racism. The goal of excluding Chinese workers led to the formation of an exclusivist mutual aid association in 1874 and then a successful union in 1880. The Columbia River Fishermen’s Protective Union (CRFPU) struck for higher prices per pound of fish the same year, gaining a small increase. The CRFPU affiliated with the brand new American Federation of Labor (AFL) in 1886. Labor disputes flared in 1896, when a strike of Columbia fishermen was busted by the National Guard, and 1902, when workers onboard company-owned fishing vessels struck while in Bristol Bay, Alaska. The ensuing discontent led to the formation of the Alaska Fishermen’s Union, which joined the International Seamen’s Union of the AFL in 1904 with 5,000 members. Like the workers that struck in 1902, most fishermen in Alaska were ‘non-residents’ who lived stateside during the off-season. While unions fought the companies, they were also complicit in excluding Alaska Natives from work in the industry

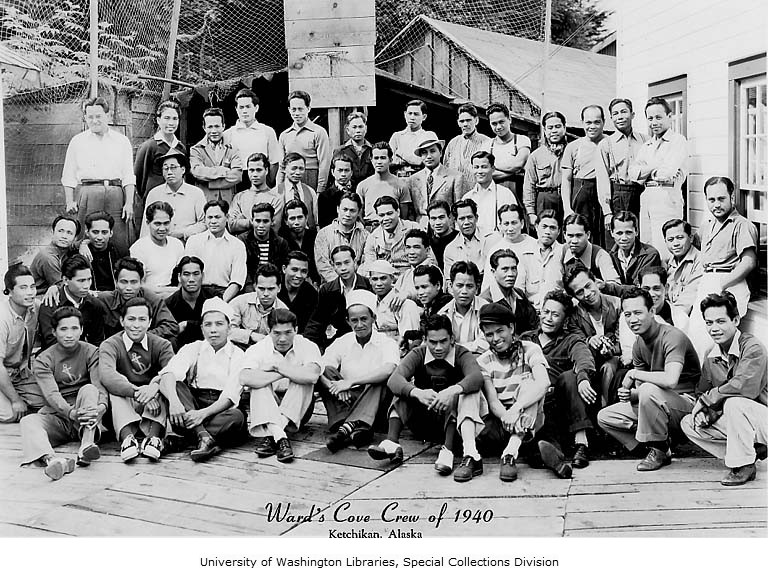

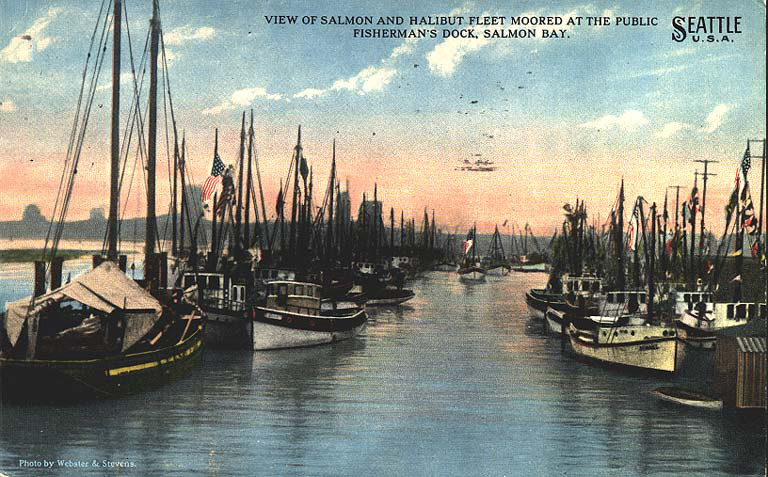

Life aboard fishing vessels became less fatal with the introduction of motors, but constant dangers including falls and engine fires continued along with the long and irregular hours of physical work. The canneries also became more mechanized, beginning with the introduction of the ‘Iron Chink’ to replace the task of gutting fish performed by Chinese migrants. Asian-Americans or European immigrant women, depending upon the area, were often the majority of cannery and processing workers. Fishing remained a largely male domain comprised of a myriad of immigrant populations. In the early 20th century, Norwegian, Yugoslavian Italian, Finnish and Japanese immigrants participated in the industry in large numbers. Immigrant communities, like Astoria, Oregon or Terminal Island in Los Angeles, revolved around fishing and canning.

The 1930s brought disruption and then a new surge of union building to the fishing industry. In 1931, as prices collapsed, wildcat strikes surged up and down the West Coast. Capitalizing on the discontent, the Seamen’s Union formed the Pacific Coast Fishermen’s Union and gave it a broad jurisdiction while the Communist Party created the Fishermen and Cannery Workers Industrial Union. Neither was successful beyond a few strongholds, but the red union introduced the idea of worker unity across crafts and throughout the supply chain. It later dissolved, merged into the Seamen’s Union and built a federation that in 1938 became the International Fishermen and Allied Workers of America (IFAWA-CIO) The industrial union united workers from San Diego to the northern reaches of Alaska, representing fishermen from all crafts and catches alongside cannery workers. By the late 1940s IFAWA represented over a third of the West Coast workforce. It was the largest and most successful fisherman’s union in American history.

It was not to last. The Cold War undermined the radical union. Expelled from the CIO, it collapsed in 1952. Remnants of IFAWA and some other localized unions, many affiliated with the Seafarers International Union, soldiered on, but faced new obstacles, including court decisions that challenged fishermen’s right to collective bargaining. Unions continued to bargain for cannery workers and for some company fishermen.

Ineffective strikes in Alaska salmon fishing in 1980 and 1991 ended the last significant vestiges of collective bargaining and unionism in the country's most important fishery. The Columbia River Fishermen's Protective Union continues to exist as an association of gillnetters with no bargaining function. They successfully defeated a ballot measure to ban commercial gillnetting in 2012, but their craft remains under threat. The Deep Sea Fishermen's Union has survived more than a century and is still headquartered out of the old Scandinavian neighborhood of Ballard in Seattle. It has less than 100 members and negotiates a contract for working conditions, among other advocacy efforts. Fishermen are still organized, often in 'marketing associations' that take a more business-style approach to fishing. Crab fishermen in California belonging to such associations struck in 2001, 2011 and 2012.

-Leo Baunach (2013)

History:

- "The International Fishermen and Allied Workers of America: Organizing Precarious Workers in the CIO Era," a five-chapter illustrated report by Leo Baunach.

- “The Fish-in Protests at Franks Landing,” Gabriel Chrisman, Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project

- “Indian Civil Rights Hearings: U.S. Commission on Civil Rights Comes to Seattle, 1977,” Laurie Johnstonbaugh, Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project (on the aftermath of the Boldt decision)

Digital Collections:

- “Salmon in the Northwest” UW Libraries Digital Collection

- John N. Cobbs Photographs

- Lummi Island Heritage. A handful of digitized IFAWA documents

Links:

- “In Their Own Words: The Story of B.C. Packers,” City of Richmond

- Guide to the Alaska Fishermen's Union Records 1919-1977, MOHAI

- Deep Sea Fishermen’s Union

- Pacific Coast Federation of Fishermen’s Associations

- Fisheries Division, Canadian Auto Workers

- Sockeye and the Age of Sail: The story of the Alaska Packers Association

- “Bellingham's Croatian Community and Commercial Fishing: A Reminiscence by Steve Kink,” Historylink

- “Canneries on the Columbia,” Oregon Historical Project

- “Sailing for Salmon: The Early Years of Commercial Fishing in Alaska’s Bristol Bay 1884-1951,” Tim Troll

- http://www.nature.org/media/alaska/alaska-bristol-bay-sailing-for-salmon.pdf

- Short digitized book

Documents:

- “Pacific Fisherman” digitized UW Libraries 1903-1911. Industry-published journal

- “Columbia River Fisheries” Digitized 30-page pamphlet, published Columbia River Fishermen’s Protective Union 1890

- “Salmon of the Pacific Coast” 1893 book by salmon cannery industrialist R.D. Hume