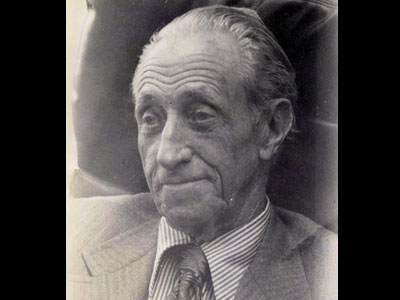

This page is an introduction to the life and work of longshoreman Harry Bridges. Below you will find a brief biographical sketch and to the right are links to videos, photos, speeches and lectures, primary source documents and other resources.

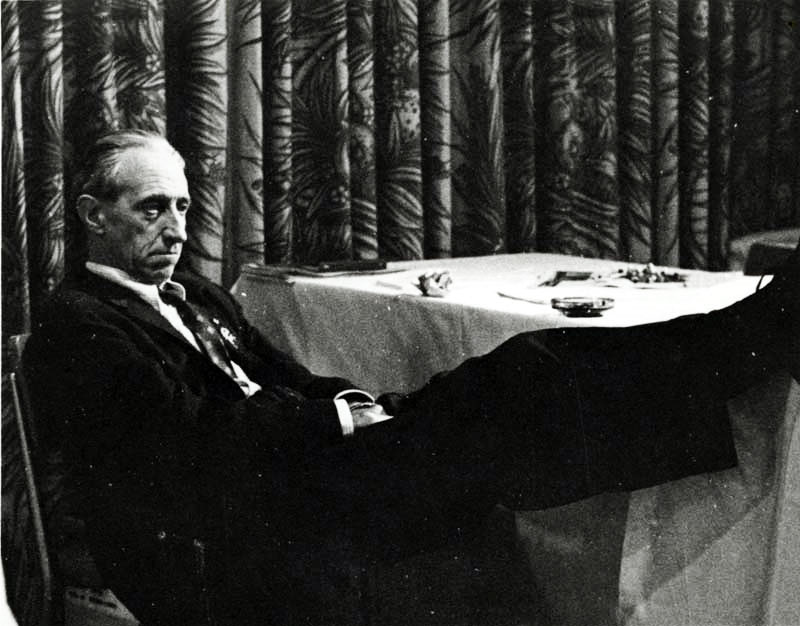

Harry Bridges was one of the most influential labor leaders in US history. Frequently at odds with conservative elements in the labor movement, and often vilified by employers and government officials, Bridges made the International Longshore and Warehouse Union into a progressive pillar of US trade unionism.

Bridges’ most remarkable contribution to labor history comes through his involvement in the Great Maritime Strike of 1934. He was a much respected rank and file leader of the ’34 strike, a strike that shut down west coast ports, led to an unprecedented three-day general strike in San Francisco, and violent confrontations on the docks. It also established the ILWU as a largely democratically controlled union, a powerhouse able to confront employer transgressions. In subsequent years Bridges was hounded by accusations of Communist Party membership and persecuted in a series of government deportation and perjury hearings. Despite his trials, Harry managed to helm the ILWU through the turbulent years of World War II and Cold War McCarthyism, increasing the union’s power and standards of living for workers. By the 1960s Bridges had moderated his beliefs and tactics, and retired from the union in 1977. His career is a testament to the ability of working people to combat arbitrary employer control and improve the living and working conditions of regular people.

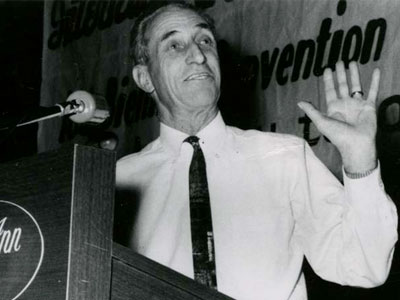

Harry Bridges and the Tradition of Dissent Among Waterfront Workers On January 29, 1994 the Harry Bridges Center for Labor Studies brought together ILWU veterans, Pacific Northwestern activists, and academics to honor and remember the legacy of Harry Bridges and the tradition of dissent he inspired on the waterfront.

Harry Bridges and the Tradition of Dissent Among Waterfront Workers On January 29, 1994 the Harry Bridges Center for Labor Studies brought together ILWU veterans, Pacific Northwestern activists, and academics to honor and remember the legacy of Harry Bridges and the tradition of dissent he inspired on the waterfront.

Harry Bridges and Seattle's Local 19 Harry Bridges met with Local 19 many times during his years as president of the ILWU. Here are summaries of forty different meetings and transcripts of five of the sessions. Local 19 has a very strong history section on their webpage, including dozens of short essays on the union, several pieces on Harry Bridges, and an amazing collection of historic photographs.

Harry Bridges and Seattle's Local 19 Harry Bridges met with Local 19 many times during his years as president of the ILWU. Here are summaries of forty different meetings and transcripts of five of the sessions. Local 19 has a very strong history section on their webpage, including dozens of short essays on the union, several pieces on Harry Bridges, and an amazing collection of historic photographs.

The Harry Bridges Center for Labor Studies Based out of the University of Washington, the Center is an online and community resource for continued labor activism and scholarship.

The International Longshore and Warehouse Union webpage has a section on the history of the union with an excellent selection of oral histories compiled by historian Harvey Schwartz.

The International Longshore and Warehouse Union webpage has a section on the history of the union with an excellent selection of oral histories compiled by historian Harvey Schwartz.

The Harry Bridges Institute was founded to meet a pressing need to educate a new generation of workers about the rich history of the labor movement; to demonstrate the working community and to showcase and celebrate the contributions of labor leaders as well as rank-and-file trade unionists, not only in the founding of unions, but in the continuous struggle for worker’s rights.

The Harry Bridges Project is dedicated to introducing the public to the life and ideas of Harry Bridges through a variety of dramatic and cultural arts.

The Harry Bridges Project is dedicated to introducing the public to the life and ideas of Harry Bridges through a variety of dramatic and cultural arts.

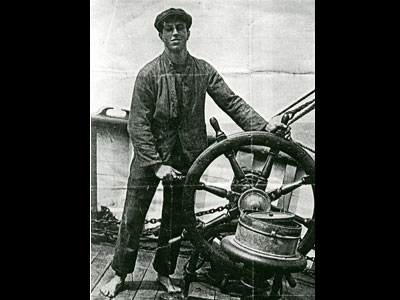

In 1920 Bridges moved permanently to San Francisco where he worked for a time as a sailor until the AFL affiliated Sailors Union of the Pacific was crippled in a 1921 strike. It was at this point that he began longshoring on the San Francisco docks. There was no regular work, and to get a job workers had to subject themselves to the hated shape-up. Early each morning those seeking employment would gather at dock gates to be selected individually for that day’s work. The throngs of people looking for work at the gates meant employers could fire any individual at any time without fear of losing a minute of work for the day. Bridges recalled the shape-up felt “more or less like a slave market in the Old World countries of Europe.”[2] Employers also used a company union to control and retaliate against the workforce through a “Blue Book” whereby a worker’s history was recorded. A clean book was necessary to get hired, and the system was used to expel pro-union workers.

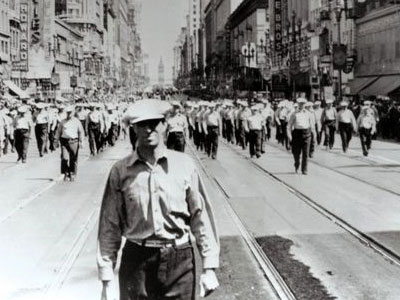

After avoiding the company union for a period and working free-lance to support his wife and children, Bridges joined the International Longshoremen’s Association when a west coast charter was granted in 1933. He quickly started working with the Albion Hall faction within the union, a rank and file group with communist influences. When the Roosevelt administration made it clear that they would back unionization through enforcement of section 7a of the National Industrial Recovery Act, Bridges and like-minded unionists used the opportunity to push for authentic union representation. In March of 1934 the ILA Pacific Coast District membership voted overwhelmingly to strike. Their demands included union recognition, an end to the shape-up through a union hiring hall, and a coast-wide contract. After some back and forth with employers, longshoremen walked off their jobs on May 9th.The ’34 maritime strike was one of the most dramatic and consequential in US history. Conflicts between strikers and police on the Embarcadero and Rincon Hill in San Francisco resembled pitched military battles; two longshoremen were killed by police in San Francisco and two in Seattle. After the killings on the waterfront the National Guard was brought in to open the SF port and disperse the strikers. During those days, and after a dramatic silent funeral procession down Market street, city opinion swung in favor of the strikers. 117 San Francisco unions voted in favor of a general strike. After three days the strike committee voted to turn the conflict over to arbitration. The longshore workers returned to work at the end of July, but it wasn’t until October, 83 days after it began, that the arbitration award was handed down. Wages and working conditions were improved, the agreement established coast-wide bargaining, and most importantly a joint employer and union hiring hall that ended the shape-up system. Bridges became one of the most highly respected militants in the ’34 strike. As member of the strike committee Bridges style of “new unionism” infuriated employers and government arbitrators, and endeared him to the rank and file.

Throughout the strike, and indeed for the rest of his career, accusations of communist membership or so-called “fellow-traveler” status dogged Bridges. The federal government tried a series of deportation cases against him in 1939, 1941, 1949 and again in 1955. The government argued that Bridges was a Communist Party member and deserved to be deported on those grounds. Bridges always denied the charges, and the government case was often weak. Government witnesses included perjurers, disbarred lawyers, and racketeers. In the early 1950s however, Bridges was convicted of lying under oath about his membership in the Party, but the US Supreme Court tossed out the conviction on technical grounds.

Despite harassment from the government and employers, Bridges moved into leadership positions in the union. He was president of the San Francisco local and head of the ILA Pacific Coast District. When the AFL–CIO split rocked the West Coast, Bridges argued that ILA-PCD should affiliate with the CIO and rename themselves the International Longshoremen and Warehousemen’s Union. Bridges was elected president of the new union and appointed as the west coast Director of the CIO. Because of accusations of Communist influence, Bridges's jurisdiction as CIO regional director was reduced and reduced again until he was finally relieved of that title. The ILWU was expelled from the CIO for being Communist dominated in 1950. Bridges remained head of the independent ILWU until his retirement in 1977.After two marriages ended somewhat acrimoniously, Harry met and fell in love with Noriko Sawada. Harry and Nikki, a Nisei Japanese American who was interned during World War II, planned to be married in Reno, Nevada in 1958. When the court clerk denied them a marriage license on the grounds that it violated the state’s anti-miscegenation law, the couple challenged the law in the courts. They won, and were married at the end of 1958; their precedent compelled the Nevada state legislature to repeal the law the following year. Not only in his personal life was Bridges committed to battling racial injustice more broadly. In his own union he consistently defended racial equality and the advancement of black and minority workers within the ILWU. Noriko and Harry were married until his death, and the ILWU remains one of the most racially progressive in the US labor movement.

The 1960s brought a series of controversies with Harry taking increasingly conciliatory stands within the union, the most important of which was the Mechanization and Modernization Agreement of 1961. The M&M allowed employers to develop containerized shipping facilities on west coast ports, and guaranteed job security, a limited form of profit sharing, and early retirement for some union members. But the deal was not all roses. Marginal union members, so-called “B-men,” lost their jobs in large numbers and many younger members grew dissatisfied with Bridges's leadership. In short the M&M modernized the ports, gave remaining ILWU members generous pay scales, and greatly reduced the number of workers required to run the docks. Bridges weathered this controversy, and many others, until he stepped down in the late '70s.  After retiring Bridges left behind one of the most radical and progressive unions in the US labor movement, a role that the contemporary ILWU continues to play to this day. Most importantly Harry demonstrated the ability of rank and file members to organize, take control of their unions, and win progressive gains despite overwhelming odds. "Put your faith in the rank and file," he was found of saying.

After retiring Bridges left behind one of the most radical and progressive unions in the US labor movement, a role that the contemporary ILWU continues to play to this day. Most importantly Harry demonstrated the ability of rank and file members to organize, take control of their unions, and win progressive gains despite overwhelming odds. "Put your faith in the rank and file," he was found of saying.

Paragon of waterfront militancy, Harry Bridges died in 1990 at the age of 88.

-- Michael Reagan (2010, 2019)