Ship Scalers Union mural

Mexican muralist Pablo O’Higgins painted a massive 58 foot mural for the union in 1945.It hung in the union hall until the Belltown building was sold in 1959. Today several panels can be seen Kane Hall of the University of Washington campus (Photo Adam Farley)

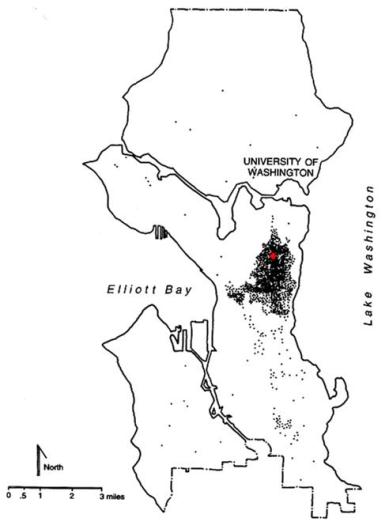

Spatial concentration of Seattle’s Black population with the location of the Ship Scalers Hall on 2313 E. Madison in red, 1960. One dot equals approximately 25 people. Source: Taylor, Forging, 195. Location of Ship Scalers Hall added by author.

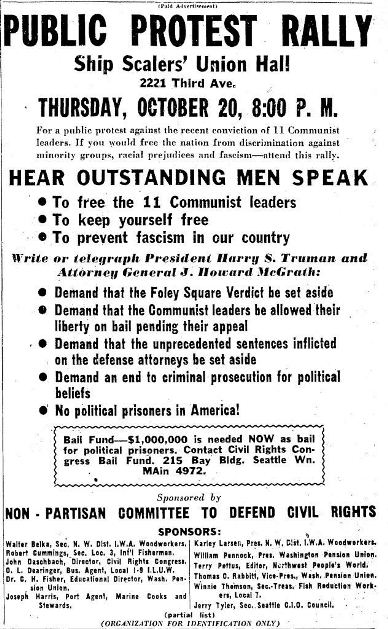

The union allowed it's Belltown hall to be used for a variety of radical and civil rights activities. Above is an advertisement for Communist Party Rally at the Ship Scalers Hall in Belltown, Seattle, 1949. Source:The Seattle Times, October 19, 1949, 13.

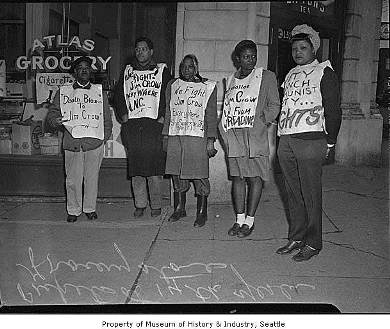

Union members join civil rights action. Protestors in front of Atlas Grocery, Seattle, 1947. The various affiliations that can be seen are: “N.N.C” (National Negro Congress) – second from left, “Ship Scalers Local 589 (A.F.L.)” – center, and “Communist Party” – far right. Source: Museum of History and Industry Digital Photo Archive

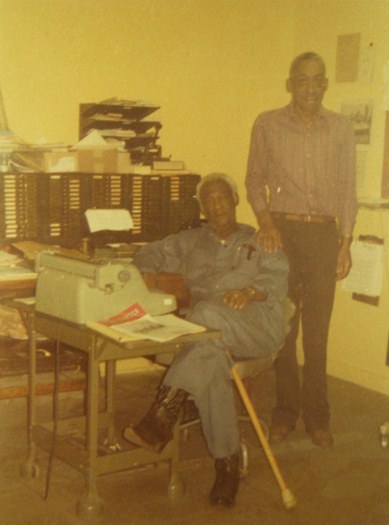

Van T. Harrison (right) and Lucius “Lucky” Jackson (left) in the Ship Scalers Hall office on E. Madison, ca. 1977. Source: Photographs, Ship Scalers, Dry Dock, and Miscellaneous Boat yard Workers Union Records, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc # 4571-001, Box 3.

by Adam Farley

On the eve of the 1934 West Coast Strike, only 1.4 percent of the waterfront workers in California were African American. In Pacific Northwestern cities, like Seattle and Portland, the number was even less. Prior to WWII, many of Seattle’s waterfront unions contained few workers of color, including the Ship Scalers, Dry Dock, and Miscellaneous Boat Yard Workers Union, Local 541.[1]

By the end of WWII, however, African Americans comprised more than half of the union’s workforce. This sea change in the composition of Seattle’s maritime workforce was a result of the migration of black workers from the East and South to the Northwest in search of wartime jobs. Indeed, between 1940 and 1945, Seattle’s black population jumped from 3,700 to more than 10,000. Forced to work in the toughest and dirtiest jobs, African American migrants came to form the backbone of the Ship Scalers Union (SSU), which did not discriminate against its black membership. Essentially, ship scalers were the maintenance crews of the docks, doing the lowest paying and dirtiest work available. Servicing ships below the waterline, these workers cleaned the inside and outside, scraping off barnacles, clearing oil drums and ship holds. [2]

After the war, many waterfront unions across the coast opened their ranks to workers of color, though often begrudgingly. Most unions found the challenge of intergration exceedingly difficult because of a historically reluctant white membership. In Seattle, reports of discrimination in shipyards were not uncommon. Al Langly, a black member of the International Longshoreman’s and Warehouseman’s Union, Local 13 in San Pedro, articulated a popular feeling among minority workers: “Most of the whites were scared of the blacks, because we never had any around here and we never associated with them…. When they started to come in, the whites didn’t want to work with them.” Langly goes on to describe active discrimination in Local 13, where there was “a kind of vigilante group of ultra-conservative” members of the union, who “had never been around blacks, or else they were southerners,” and resolved to maintain the union’s white character through active exclusion.[3]

The example of Local 13 reflects a larger West Coast trend. Prior to WWII, most unions had few, if any, African American workers unless there was a segregated auxiliary set up, as was the case among many locals of the International Brotherhood of Boilermakers and other unions.[4] As the United States became further involved in the war effort, black workers from the South came to the shipyards to fill the labor shortages created by white workers gone to war.[5]

In most unions, the transition in labor force racial demographics was, according to historian Bruce Nelson, “not an easy one,” but for the Ship Scalers Union in Seattle the transition occurred naturally and without constraint, marking Local 541 as an anomaly among West Coast Unions. As early as 1941 the SSU published anti-discriminatory articles in its newsletter, and allied itself with the minority worker and even “foreign-born Americans” after the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor.[6]

In a 1982 Seattle Times feature of the union, Dick Clever recounted the Ship Scalers Union apparent seamless transition (and nebulous beginning): “Consensus has the Ship Scalers local established in the mid-1930s by Norwegian shipyard workers from Ballard. The Norwegians drifted into the craft unions representing more skilled workers, and the Ship Scalers came to represent, as it does today, those performing some of the dirtiest, most dangerous tasks in Puget Sound’s shipyards.” African Americans in the Northwest’s shipyards were by and large barred from the craft trades, and, Clever continues, “found themselves with the lowest-paying, dirtiest jobs—and of necessity, with the Ship Scalers Union.” This “necessity,” as Clever called it, pushed the union in a new activist direction. From the mid-1930s to 1986, Local 541 of the Seattle Ship Scalers Union articulated a broad political agenda to address specific maritime employment conditions, as well as the struggle for civil rights and social change. [7]

For much of the twentieth century, Seattle’s racial discrimination in employment, schools, and housing echoed the national norm, though perhaps in more hidden ways from those in the South or Northeast. It was in this realm that the SSU found its cause to fight against tacit discrimination in the city. Indeed, Clever notes that “there has been hardly a time when Local 541 was not embroiled in controversy, whether external or internal.” From WWII on, the Ship Scalers Union played an active and integrated role in Seattle’s social history, especially Seattle’s black community’s fight for equality. By allying itself with Seattle civil rights organizations, using its union hall as a meeting place for political activism, and allowing both communists and African Americans to be freely admitted to its ranks, Ship Scalers, Local 541 emerged as a progressive voice and effected some of the most significant civil rights reform in the city, both within and outside the shipyards. Although the union’s social activism waned in the 1960s and eventually dissolved in 1986, it remained an important fixture of the Seattle waterfront and the black community until the transfer of their jurisdiction. [8]

Origins in Seattle’s Waterfront Minority Community

For the Ship Scalers Union, along with other maritime industries, the 1934 strike marked the beginning of black workers’ entry into the shipyards as permanent members of the waterfront community. Insofar as African American laborers found work prior to the strike, it was mainly as strike breakers, and even then only temporarily. What changed during the 1934 strike was that West Coast unions realized in order to be an effective seat of power among workers, there could be no ample body of non-unionized laborers. Under the leadership of Harry Bridges, the International Longshoreman’s and Warehouseman’s Union was among the first to take steps towards integration. In California, Bridges implored black workers to join the strike and man the picket lines, speaking in black neighborhoods of the San Francisco Bay area and in black churches.[9] Reflecting on the strike and his efforts towards integration, Bridges claimed that “I went directly to them. I said: ‘Our union means a new deal for Negroes. Stick with us and we’ll stand for your inclusion in [the] industry.’… [A]lmost without exception, they stuck with us. They helped us. The employers were frustrated in their attempt to use them for scabs.”[10] Although Bridges fell short on the promise for some locals of the ILWU, by and large, black workers were able to gain employment in the West Coast shipyards.

What the 1934 strike began in terms of racial integration on the waterfront and in the Ship Scalers Union, WWII catalyzed. In Seattle, the black population grew by 413 percent between the years 1940 and 1950, and more than 45,000 African Americans migrated to the Puget Sound region to seek work in the defense industries.[11] Among both black and white migrant workers, largely from the rural South, the consensus was that Seattle represented a sort of promised land for employment opportunities, and for blacks specifically, equal employment opportunities. Historian Larry Richardson writes, “African-Americans who migrated improved their lot,” and that Seattle was “the end of the line both socially and geographically. There was no better place to go.”[12] This was relatively true when compared to other west coast cities, but even in Seattle, there was mounting racial tension. At the beginning of the war nearly every wartime industry except the waterfront still barred blacks from work, including Boeing, Pacific Car and Foundry, and Doran Brass, among others. It is not surprising then that most black workers came to work in Seattle’s twenty-nine shipyards and that by the war’s end, 4,078, or seven percent, of the 60,328 shipyard workers were African American.[13] In his history of the black community in Seattle, Quintard Taylor explains the reason for Seattle’s shipyard liberalism:

Unlike other West Coast cities, no major company dominated Seattle’s shipbuilding industry. In addition to the Todd and Seattle-Tacoma shipbuilding companies, the largest in the region, the twenty-seven other shipyards in the Seattle area collectively employed about 60 percent of the shipyard workers. Furthermore, the powerful International Brotherhood of Boilermakers, which dominated shipyards in Portland, the San Francisco Bay area, and Los Angeles, had exclusive bargaining agreements only with Todd and Seattle-Tacoma Shipbuilding….Consequently, Seattle’s African American shipyard workers were not segregated into auxiliary locals of the Boilermakers union, nor were they denied promotion opportunities….While there were sporadic complaints of discrimination in Seattle’s shipyards, the systematic segregation of blacks that persisted throughout the war years in other West Coast ship construction facilities did not evolve in Seattle.[14]

However, any joy surrounding this integration should be tempered. While the SSU itself did not discriminate, many companies, boat yards, and individuals did, and the excess of workers allowed easy routes for segregation in the workforce. There was plentiful work on the waterfront and for ship scalers, but this employment availability was not a singular victory. Many hiring halls along the coast served as de facto sites of discrimination. Workers could readily be replaced if the working conditions were not favorable (i.e. if they were forced to work with workers of other races). In an oral history interview with Bruce Nelson, black longshoreman Walter Williams of the San Pedro Local 13 recalled that “some of the regular ‘longies’…would say, ‘I’m going to call me a damn replacement,’ if they saw a black guy coming down into the hold. And they would call a replacement rather than work with us.”[15] Seattle shipyards and members of SSU were not the exception to this trend. One pre-war edition of the Scaler’s News reported discrimination at the Associated Shipbuilders yard where four workers were refused the right to work after showing up at the yard because two of them were black.[16] This demonstrates the discriminatory practices of shipyards not only towards African Americans, but even to those who affiliated with them. The article itself is a terse summary, but that it was newsworthy for the SSU paper indicates a growing discontent with Seattle’s racial climate.

When general integration in Seattle did arrive during WWII, it was not spurred by moral justice, but by the sheer excess of work and a lack of laborers to do it. Del Castle, secretary-treasurer of the Ship Scalers Union during the WWII years, recalled with a certain facetiousness in 1982 that the Ship Scalers “got into the complicated problem of unions discriminating, but labor was so short that the King County Labor Council agreed that it was their patriotic duty to accept black workers into their ranks.”[17] Most migrants arrived in Seattle to find the racial conditions better than where they left, but not as ideal as they had hoped. Most came to believe that Seattle’s existing residents of color “had not been aggressive in asserting their civil rights, and thus, claims of ‘good race relations with whites’ were vastly exaggerated.”[18] The tension between old residents’ racist attitudes and practices and recent migrants grew. The migrants soon sought to improve their situation by their own hand, and as Castle articulated, he and the SSU dynamically participated in that struggle.

World War II Activism

For the Ship Scalers Union, the United States’ entry into WWII marked a turning point in activism. Prior to the war, the union did not contain restrictions on membership in terms of race and openly admitted workers of color. Once the war started, the white-majority SSU turned its efforts to aggressively publishing outspoken messages in support of equal rights and chastising discrimination as fascist and “playing into the hands of Hitler.”[19] The December 1941 issue of Scaler’s News came out strongly against discrimination in the shipyards and waterfront unions: “The Trade Unions, together with all other organizations of the people, regardless of race or color, must concentrate their combined forces against the enemies of the Nation!”[20] This rhetoric and call for victory abroad and unification at home can be seen as part of the national “Double V” campaign during the war. Many African Americans felt that a simultaneous war was being fought against Jim Crow laws in America. In 1942, James G. Thompson wrote to the Pittsburg Courier questioning how Americans can fight in a war against tyranny overseas when “ugly prejudices here are seeking to destroy our democratic form of government just as surely as the Axis forces.”[21] For many African Americans, the fight against fascism abroad was a fight against Jim Crow. The Double V campaign led the SSU to engage in a national dialogue as opposed to concentrating on local civil rights issues. It is clear that the SSU’s devotion to civil rights went beyond the pragmatic integration of many unions and shipyards and indeed, formed the basis of an involvement in civil rights struggles in future years.

In December 1941, the SSU also adopted a “Declaration of Policy on the War Against the Axis,” which was voted on in a regular membership meeting and published in that same edition, calling for:

Vigilance against spies and enemies of our country; rejection and condemnation of all efforts to break up our national unity through Negro baiting, Jew baiting, and other means of dividing us; friendship with U.S. Japanese, Germans and Italians loyal to our democracy; sympathy with the unfortunate and misinformed people of Japan, Germany, and Italy, for we fight not alone in defense of our liberty and independence, but for their liberation and right to democratic rule as well, against their Fascist Dictators.[22]

Throughout the war, the union not only abided by their “Declaration of Policy,” it also involved itself socially and politically on the waterfront by directing other unions to do the same. In June 1941, President Roosevelt signed into law Executive Order 8802, which prohibited discrimination in firms with government contracts, and while this allowed de jure equality, the SSU recognized that many Seattle unions were not acting in accordance. Initially, SSU’s tactic was to lead by example and implore other unions to follow through the use of news articles and distributed pamphlets. One such article stated, “The attitude of the Scaler’s Union may well point the way to some of the other Unions who do not as of yet recognize that racial discrimination plays into the hands of Hitler and slows up our war effort.”[23] The language used in the Ship Scalers Union articles was radical in and of itself, but that the union also donated funds to the American Committee for the Protection of Foreign Born, and distributed such flyers demonstrates an extended and almost militant commitment.

As the war progressed, the SSU became more vocal and actively militant about their opinions. One such incident occurred on July 19th, 1944. Three members of the Ship Scalers Union were arrested for heckling the American Friends Service Committee at a public meeting in Seattle. Del Castle, Hugh DeLacy, and Fred Berry, three of the union’s most progressive members (Berry and Castle were both members of the Communist Party) claimed they did so because “the speakers favored a negotiated peace with the Axis.”[24] Castle felt it was his duty as an American to dissent because he “didn’t like what the group was saying.” Berry went further by telling The Seattle Times that he did not favor freedom of speech for “certain groups.”[25] Indeed, the union was able to effect changes in waterfront politics—Castle and others convinced unions to cooperate with communist sympathizers and by the end of the war, King County adopted a fair practices policy before it became state law.

The open social involvement and non-discriminatory practices of the Ship Scalers Union not only effected changes in Seattle civil rights during the war, it also led to a near inversion of the union’s racial demographics. At the conclusion of the war, Van Harrison, one of the first black men admitted to the union in 1940, guessed that the union was “about ninety-five percent black.”[26] African Americans were drawn to the SSU in part because it represented the least skilled positions for the greatest rate of constant work, but also because the union’s policy on admitting new members was liberal and unrestricted. In 1982, Harrison recalled that “you could work for a while on a permit and then, if you had three sponsors, you could join the union.”[27] Three sponsors would not be difficult to come by as the union enforced its anti-“Negro baiting, Jew baiting” policy among its members. In addition to three sponsors, all the application forms asked basic biographical information, the applicant’s address, veteran status, when were they discharged, and how long they worked out of the union hall.[28] The most common reason for refusal of an application was insufficient time as a ship scaler, but usually by the next monthly general assembly meeting the applicant would be invited to join.

Post-War Militancy and Communist Ties

During and especially after WWII, many members of the Ship Scalers Union maintained dual membership in the union and on Seattle civil rights councils, making a web of influence that the union could call on at any moment in a given political situation. This trend continued throughout the union’s history, though their involvement waned in the 60s. An important moment for the union came just prior to US entry into WWII, when the SSU put its efforts towards re-electing Hugh DeLacy for city council in the 1940 election campaign. DeLacy, an English professor at the University of Washington, was a popular liberal member of the Seattle City Council with close ties with the SSU. As a councilman, DeLacy argued for reform of the city’s civil rights policies, especially in favor of overturning Seattle’s racially restrictive housing covenants.[29] Though he was defeated in 1940, DeLacy joined Local 541 because, as one Seattle Times article put, he “sought a more ‘strenuous occupation.’”[30] In 1944, the Ship Scalers Union again supported DeLacy in his election campaign for State Representative of Washington’s First Congressional District, which encompassed Seattle. DeLacy ran successfully as a New Deal Democrat and quickly became an advocate for labor interests and ending public housing segregation. He was defeated in Washington State’s 1946 electoral backlash against many House Democrats and returned to Seattle as a shipyard worker. His final election campaign in 1948 was again supported vehemently by Local 541, as well as other well-known political activists. Historian Quintard Taylor notes that he even published “campaign literature featuring black political activist Paul Robeson.”[31] Although he lost, his defeat was not unique to national trends against leftist politicians. DeLacy’s campaign was outspoken about price controls and against the formation of the House Committee on Un-American Activities.[32] DeLacy marked the peak of the Ship Scalers Union’s involvement in the national dialogue of the era, as the SSU enjoyed a direct representative in the House who supported labor rights and civil rights in the state.

Despite DeLacy’s political losses, on a local level the Ship Scalers Union was involved in city affairs throughout the 1940s and into the 1950s. As early as March of 1940 (before the union was predominantly African American), the union sat a delegate to the King County Civil Rights Committee.[33] During WWII, the SSU sent DeLacy to the Convention of the American Committee for the Protection of the Foreign Born, arguing in Scaler’s News, “The preservation of civil rights is a vital part of a democratic war.”[34] The union had ample motive to be involved in civil rights activism. Seattle, while it was perceived to be liberal-minded, took nine years to pass legislation on employment fair practices. In 1946, the Seattle City Council rejected a fair practices bill that would have barred restrictions on membership in unions and by employers on the grounds of race. Del Castle, then secretary-treasurer of the Ship Scalers Union, was one of the speakers named in support of the bill who gave arguments at the public hearing. The hearing was so heated that, according to a Seattle Times article published about the rejection:

Councilman M. B. Mitchell, chairman of the hearing, had to rap sharply for order after many in the audience jeered when Howard F. Smith… arose to protest the suggested ordinance….Smith, who half turned around to face the audience from his seat at the front declared that the suggested ordinance’s principle support came from “a group which tries to stir up hatred between races…whose whole program is to sabotage our economy while Soviet Russia is working day and night.[35]

Interestingly, the same rhetoric used by Smith was used five years earlier by the Ship Scalers newsletter in support of removing racial restrictions. This suggests a more advantageous, rather than logical or ethical, form of argumentation by Seattle’s opponents of civil rights at the time. Indeed, this was undoubtedly a trigger of the increased militancy of the SSU and Seattle civil rights supporters. Castle was also a member of the Seattle Interracial Action Committee, which allied itself with other organizations including the Seattle chapter of the Civil Rights Congress. According to Quintard Taylor, the Civil Rights Congress was emerging as an activist organization, “willing to use boycotts, pickets, and demonstrations to mobilize public opinion.”[36] These were tactics the Ship Scalers Union embraced. A 1947 photograph shows a member of the Ship Scalers Union protesting with other black members of various organizations (including the National Negro Congress and the Seattle Communist Party) in front of Atlas Grocery on 14th and Yesler in Seattle’s Central District (see Figure 1). The photograph evinces the alternative stance of organizations like the Civil Rights Council, the National Negro Congress, and the Negro Labor Congress, which reacted against the more temperate legislative and judicial measures taken by the NAACP and the Seattle Urban League. As an involved organization within Seattle’s civil rights conversation, the SSU drew national attention to itself through its activism. In 1946, it received a letter of invitation to “meet with Revels Cayton, National Executive Secretary of the National Negro Congress… because of recognition of the fact that you are deeply concerned with the affairs of our community and our country.”[37]

In addition to being involved in civil rights issues, the early years of the Ship Scalers Union was strongly communist. Many of its key members and officers were either openly and actively Communist Party members (such as Berry and Castle), or supporters of communists (such as DeLacy). These members of the union pushed Local 541 in the direction of militant politics and sought an end to discrimination and reducing political conflict in the shipyards. Berry and Castle were the two most prominent Communist Party members in the Ship Scalers Union. Berry was one of the first black men admitted to the union in 1940, and that same year was elected business agent of the union.[38] When Castle joined the SSU in 1940, he was a white University of Washington student, member of the Young Communist League, and was a member of the Communist Party of America.[39] Both Berry and Castle were officers in the union, Berry as the business agent, and Castle as the secretary-treasurer, meaning together they were in charge of soliciting funds and distributing the union’s money. Under their leadership, Local 541 raised money for the Russian war relief, arguing in the Scaler’s News, “‘what would be our chances for victory be IF THE SOVIET UNION WAS NOT FIGHTING ON OUR SIDE’ – we can readily agree that the collection of funds to help them is a mighty worth while thing to do.”[40] The union’s support of communism allowed them to participate in a more revolutionary dialogue on both a national and political level. This demonstrated that the struggle for racial equality was not just restricted to local affairs, but emphasized that it was part of a larger and more fundamental problem that affected the entire American population.

During WWII, support for communism within unions and on the waterfront lessened, but under the progressive leadership of Castle and Berry the union remained involved in communist causes. Local 541 was also mildly successful at creating an accepting environment of left laborers on the waterfronts of Seattle. In a 1982 interview, Castle articulated his goal to achieve wide support of a Communist Party Congress program that promoted a united and progressive front in the fight against fascism. One of the most evident effects of the SSU’s affiliation with Communists was when Castle was able to convince Seattle unions to adopt a “grudging acceptance of the need to cooperate with the ‘reds’… at least while the Soviet Union was an ally.”[41] This alliance coincided with the King County Labor Council’s admittance of black workers into its ranks, indicative of the SSU’s success in Seattle at integrating communist support with civil rights reform. While Castle was electorally defeated as the secretary-treasurer in 1946, Berry was still an officer in the union until the early 60s. Despite growing opposition to the CP cause and Castle’s departure, Local 541 remained involved in communist Seattle, continuing the tradition begun during the war years.[42]

The main effect of Castle’s election loss was a transition from open support of Communist tenets to a more general agenda for freedom of speech and political equality of voice. Just after the war, the “grudging acceptance” waned again, especially by the Scalers’ international union, the International Brotherhood of Boilermakers, affiliated with the American Federation of Labor (AFL). On Labor Day of 1946, The Ship Scalers Union defied the AFL by marching in a parade hosted by the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). The Seattle locals of the AFL declined to march because they considered the CIO communist sympathizers.[43] Then on April 2, 1947, Gerhard Eisler’s wife was set to speak at Moose Hall in Seattle. Eisler was a prominent Polish Communist on a tour of the United States, petitioning for funds to aid in her husband’s lawsuit against the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Three days before Eisler's scheduled rally, the HUAC barred her from speaking at the hall. As one of the sponsoring organizations of her tour, the SSU welcomed Eisler to instead give her speech at the Scalers Hall, raising more than three-hundred dollars for the couple’s case.[44]

After the war, the Ship Scalers Union was able to retain its communist stance, though the lexicon of supporting rhetoric had changed. In direct response to the House Un-American Committee hearings, specifically the Canwell Committee, the SSU organized a “Lenin Memorial Rally” at their union hall in 1948. The rally was co-sponsored by the Washington State Communist Party, prompting one Seattle Times article to call it a “War Fund” in the “fight against ‘reactionism.’”[45] The language used by both the Times and the SSU in their advertisements suggests a growing polarization with respect to the issue of the “enemy within,” and only heightened the SSU’s resolve to support political unification in the United States. In this light, the SSU’s support of communism is less a direct advocacy of orthodox communism and more of a fight for political respect, intelligent conversation, and equal representation of the citizens’ voice. Still, their affiliation with communism gave that struggle higher and more urgent stakes as representing a more important political problem.

Throughout the Ship Scalers Union’s activism in the decade following the war, their hiring hall, located at 2221 Third Avenue in Seattle’s Belltown neighborhood, acted as the seat of influence and locus of radical and leftist laborers in Seattle, including a broader community and civic center near the waterfront. Even though the SSU was not affiliated with the CIO, in 1949 they hosted in their hall a convention of the CIO Council. What was termed by The Seattle Times as an attempt “to reunite all CIO unions in Seattle,” highlights the SSU’s commitment to unity among laborers, regardless of affiliation.[46] Later that same year, and recalling the Lenin Rally of 1948 at Ship Scalers Hall, the SSU held a “Public Protest Rally” on October 20th. The rally was sponsored by the Non-Partisan Committee to Defend Civil Rights and described its aim in a quarter-page paid advertisement in The Seattle Times: “For a public protest against the recent conviction of 11 Communist leaders. If you would free the nation from discrimination against minority groups, racial prejudices and fascism—attend this rally” (see Figure 2).[47]

The years 1949-50 were perhaps the busiest years for the use of the Ship Scalers Hall as a congregating place for progressives in Seattle, holding on average one rally, featured speaker, or convention every two to three months. In a follow-up speech to the Public Protest Rally, the Ship Scalers Union brought the defense attorney for the eleven Communist Party leaders to the hall in 1950 just after the trial’s conclusion.[48] By far, the most significant voice the SSU was able to draw to Seattle was that of W.E.B. Du Bois, founder of the NAACP, in 1951. Du Bois, 83 at the time, gave a speech titled “Peace and Freedom.”[49] Beyond the political gatherings though, the Ship Scalers Hall played host to the Seattle Philharmonic and Choral Society who practiced each Friday night there in the early 50s and screened movies in its large hiring hall. One 1952 flyer advertised Peace Shall Win, and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (see Figure 3).[50] In “an era when communists and socialists organized workers with an urgent sense of mission,” as Dick Clever describes it, the Ship Scalers Hall played the role of the Roman Forum, a place for political discussion, social gossip, job opportunities, and plain old low-brow entertainment.[51]

Eventually, the judiciousness of organizations such as the NAACP and the Seattle Urban League won out against the backdrop of the House Un-American Committee hearings. Organizations worried that their politics and methods would be taken as a pairing of civil rights agendas and “leftist” elements, a contemporary euphemism for “Communist.”[52] Indeed, in 1949, Albert F. Canwell, a state legislator from Spokane, rearticulated the notion given by Howard Smith by saying, “If someone insists there is discrimination against Negroes in this Country, or that there is inequality of wealth, there is every reason to believe that person is a Communist.”[53] As a result of the national changing opinion toward communism, the SSU not only distanced itself from communist politics, but also ceased to associate actively with civil rights reform in order to avoid associating equal rights with communism, much like the NAACP and the Urban League sought to do through the democratic process. In a sense, the SSU was tainted by its Communist Party ties and any activism would be seen in that light by a dissenting public. Consequently, vehement anti-communism limited the extent of the SSU’s influence on civil rights change.

By the mid-1950s, Local 541 retreated from an activist role and resigned itself to manage politics that were, according to Clever, “directed toward the ‘bread and butter’ issues” of running the union and dealing with employers and contracts.[54] This is partly reflected in the meeting minutes throughout the 1950s, which dealt primarily with such issues and occasionally mentioning some form of civic involvement. In March of 1955, the SSU voted to donate twenty-five dollars to a strike of electrical workers against the Westinghouse Electrical Company for better working conditions and wages. At the same meeting, they moved to send a letter expressing “support for Montgomery, Alabama bus boycott.”[55] Throughout the 1950s and into the 1960s, there are traces of the union’s imprint on the national scene of civil rights reform, sending letters to President Kennedy and to the city of Birmingham, expressing disgust at the 16th Street Baptist Church bombings. Aside from these notable instances, the union largely retreated from progressive politics. As a former vocal and active participant in local affairs, the Ship Scalers Union became only tacitly involved in civil rights politics when they came up, but was no longer able to be an instigator of civil rights reform by itself.

Decline in Public Activism

In 1959, the union was forced to sell its Belltown hiring hall and relocate to 2313 E. Madison St. in Seattle’s Central District. This move marked a significant transition from Local 541’s public activism in the 1940s and 50s to its last quarter-century of internal struggle and episodes of mismanagement. This is not to say that the union completely removed itself from progressive affairs, but that the primary focus of the union after 1960 was either internal or specifically related to its members. One of the most poignant moments for the union came in 1965, when then president Van Harrison was part of a panel discussion titled, “Are Labor Unions the Lost Sheep of Social Reform?”[56] This reflects not only the Ship Scalers Union’s limited political participation, but also the growing trend of unions losing effectuality in areas outside of strict labor reform. Just one year earlier, Harrison was an idealistic member of the King County Economic Opportunities Board as part of the city’s anti-poverty campaign. The board was a fledgling campaign at best, foreshadowed by The Seattle Times headline about its slow beginnings: “Antipoverty Board Off on ‘One Wing.’”[57]

The SSU’S move to the Central District was symbolically important. The SSU’s new location in the north end of the Central District demonstrated an increased solidarity with the city’s black community in sprit and necessity. By 1960, Seattle’s black population was 26,901, and according to Quintard Taylor, about seventy-five percent of them “lived in four Central District census tracts, and by 1965, eight out of ten black residents lived there – the highest percentage in the city’s history”.[58] It is thus not surprising that the Ship Scalers Union chose to relocate in the northern business area of the Central District (see Figure 4). For the most part, Local 541 let bolder organizations lead the fight for civil rights in the 60s, occasionally throwing their name in as a supporting organization. This retraction may have to do simply with the relocation of the union hall out of the centrally located neighborhood of Belltown, and the considerable size difference between the halls. The new union hall was significantly smaller and lacked an auditorium, preventing the SSU from staging wide-scale rallies or major events in the new building.

By the early 60s, there was growing idealism among African Americans in Seattle, and a reaction against the efficacy of the 1950s NAACP and Seattle Urban League. Inspired by national movements, Taylor writes that African Americans in the Central District engaged in “direct action campaigning to end job bias, housing discrimination, and de facto school segregation in Seattle as an integral part of the national effort to eradicate racism, empower African Americans, and achieve the full and final democratization of the United States.”[59] Despite some successes, the majority of African Americans living in 1960s Seattle were disheartened by failures, especially in relation to school segregation. Taylor argues that Seattle’s minority residents “sought instead to build a community within the Central District free of the economic and psychological control of white Seattle.”[60] It is in this context that the SSU hall location and their transition away from overt militancy becomes significant. At first glance, it may seem to represent a deeper entrenchment within Seattle’s black community, but in actuality, it was a move inwards that prefigured the trend of many Seattle civil rights organizations later in the decade.

Even though the 1960s marked a decline in social activism for the Ship Scalers Union, it remained dedicated to improving working conditions for members, retaining at least some of the vigor of the early days of the union. The most significant event of the decade for the Local 541 was in fact three separate strikes at the Lockheed Shipyard over a period of four years from 1966 to 1970. The first strike occurred between August 25-29, 1966 over a reported dispute about supervision of the SSU being transferred outside the union. On the first day, 140 members of the union left work at ten in the morning to attend an internal meeting about the change in supervision. They stayed on strike for the next four days until a settlement was reached that allowed unionized ship scalers to remain under the supervision of nine-year ship scaler veteran James Wilson.[61] While the dispute was in essence only with Lockheed, it represented a greater theme in the history of the SSU’s quest for autonomous working conditions and supervision. In much the same way that the Ship Scalers Union sought to free the country of fascists during WWII, they now narrowed their scope and demanded the right to work as a unified group within Seattle’s maritime industry under familiar leadership. As a continuation of the union’s activism, the Lockheed dispute effectively galvanized support for solidarity among ship scalers working in Seattle’s yards.

The second strike further reflected the union’s desire for familiar leadership, but this time with racial overtones, signifying a desire to remain involved in civil rights, even if on a smaller scale. In late December of 1967, Lockheed changed supervisors without announcing it to the SSU in order to avoid a strike. Instead, the roughly 170 ship scalers working at Lockheed walked out again on January 3, 1968 one week after Painter’s Union member Rube Plunge was named as supervisor.[62] By January 9th, a settlement was reached that removed Plunge and instated a member of Local 541 named George Walker as the ship scalers’ supervisor. The SSU argument was two-fold: They argued that scalers “were being deprived of their own supervision,” and that the change in supervisors was due “partly to discrimination” because, as the Seattle Times reported, “Wilson and Walker are Negroes. Plunge is Caucasian. A majority of members of the union is Negro.”[63] The fact that this strike was directly attributed to race is important. It demonstrates the SSU’s belief that the equal employment on the waterfront was neither complete nor totally equal. Furthermore, the Ship Scalers Union’s ability to mobilize and support its rank and file to achieve its ends illustrates the influence they still wielded at the end of the 1960s.

Even though Del Castle, Fred Berry, and Hugh DeLacy departed from the union and the Ship Scalers Union moved away from the waterfront, the SSU still supported its own workers and remained involved with workers’ issues throughout its existence. The final strike in the series of disputes occurred in October of 1970, when 175 Ship Scalers walked off Lockheed’s shipyard again. This strike was not regarding supervision, but the computing of vacation pay as well as the handling of fiberglass in the shipyard that became part of the Ship Scalers Union’s contract with Lockheed in July of 1968. The strike only lasted two days and ended in a grudging settlement by Lockheed to pay back vacation and $282.88 to every worker as premium pay for handling the fiberglass.[64] According to secretary-treasurer/business manager Van Harrison, disputes with Lockheed were occurring since 1959 and the 1970 strike represented the culminating point. It also was one of the last battles the SSU fought outside their union, as the next decade and a half would be marked by internal struggles with their international affiliate.

Trouble with the Laborers’ International Union

The Ship Scalers Union’s relationship with the Laborers International Union of North America (LIUNA) was strained almost from the beginning of their affiliation and culminated in an irresolvable dispute with LIUNA in the 1980s, ultimately leading Local 541 to be dissolved and control of their jurisdiction transferred to another local. Their relationship began in 1956 when the SSU disaffiliated with the International Brotherhood of Boilermakers and sought affiliation with the International Hod Carriers’, Building and Common Laborers Union of America.[65] Initially, the Ship Scalers Union’s motives for the change in affiliation were more or less practical. A Seattle Times article described the SSU as “having been cast off” from the Boilermakers, and “forced to seek affiliation with the Laborers’ International.”[66] Most of the West Coast Ship Scalers unions were at the time affiliated with the Hod Carriers, so it is not a surprising move because the Ship Scalers Union had to ensure its bargaining strength with employers. In their application for charter to the Hod Carriers, the union listed only 400 members, a relatively small and manageable union by the standards of the day.[67] Indeed, the SSU itself was clandestine about the nature of its departure from the Boilermakers. In the meeting minutes of an officers meeting, George E. Flood argued that a letter sent to the Hod Carriers need not be “in complete accordance with all the specific details [of their motives for the affiliation change].”[68] This seems to suggest either a significant dispute with the Boilermakers or that the Ship Scalers Union preferred to withhold information from the Hod Carriers, or possibly only that the motives did not concern the Hod Carriers.

Whatever the reasons for changing affiliation, the Hod Carriers represented a better and brighter future for the members. The 1956 preamble of the Hod Carriers constitution argued “that all human-kind is created equal, and are entitled to the basic human right of providing a living for themselves and their families…. [and] that all people of the earth who labor for the advancement of capital are entitled to an equitable share of said advancement, as well as the right to organize and to achieve advancement through colective [sic] bargaining.”[69] This was similar language the Ship Scalers Union used in its push for equal opportunity employment, and half a decade earlier when rigorously supporting communism. In the mid-1950s, many Boilermakers locals either discriminated against admitting black members or established quotas for minority workers. It was more than likely that partial motivation lay in the SSU’s hopes to have a strong and progressive international to support their own forward agenda.[70] This mutually beneficial relationship did not develop and instead LIUNA became representative of the dictatorial governance that the union fought strongly against during WWII.

Prior to official affiliation with the Hod Carriers, the Ship Scalers Union were disputing with the local of the Hod Carriers. A 1955 letter sent to both unions from a non-affiliated waterfront attorney lists mutually agreed upon terms of settlement that were resolved on February 4th of that year. The dispute was over jurisdiction in the cleaning of ships, specifically how jurisdiction changed depending on whether the entire boiler was to be removed or not.[71] While a relatively minor dispute, it signified a long history of strife. In 1958, the letter was sent again, this time by an attorney of the Hod Carriers, explicitly “reminding the Ship Scalers of their agreement,” who apparently were still performing duties that were allotted to the Hod Carriers.[72] The Seattle Times historian Dick Clever called it an “uneasy relationship at best,” revealing that the Hod Carriers “insisted on collecting half of all monthly dues paid by members of Local 541, regardless of whether the local received services for its money,” which the majority of the time it did not.[73] Instead the fees, augmented by poor management, nearly bankrupted the SSU.

The fourteen-year “irresolvable dispute” with LIUNA, which ended in the transfer of control of Local 541, began in 1972 when the general membership of the union attempted to remove Secretary-Treasurer Van Harrison from office. A generous and involved president of the union, Harrison ran for the joint position of secretary-treasurer/business agent in 1968 and won. The two positions were combined in the early 60s to save on salary costs; this meant that the officer in charge of incoming funds and the officer in control of spending were the same person. In a union without a strong history in bookkeeping, this was an ominous move. As far back as 1955, a Labor Department audit “scolded the business manager for not being able to account for large quantities of cash.”[74] As supported as Harrison was in his election to the position, he was equally desired gone by 1972. An election was held in which Oscar Hearde ran against Harrison in an electoral meeting that was adjourned because of rampant disorder (see Figure 5). Among the charges lobbied against Harrison were: Refusal to allow members to see financial reports; lack of record keeping for receipts;[75] and, most egregious, the unilateral transfer of jurisdiction of work for certain tasks away from the members of the Ship Scalers Union in the shipyards. Harrison was eventually suspended (along with Lucius “Lucky” Jackson), but LIUNA backed Harrison and Jackson by invoking a technicality of the union’s by-laws and reinstated them both in 1973 (see Figure 6).[76] LIUNA’s heavy-handed action of the Harrison-Jackson affair marked the beginning of the SSU’s struggle for management of its own affairs. After a series of hearings in 1973, most of the rank and file was disillusioned with LIUNA, and many, including Hearde, retreated from union politics. In the remaining years of the decade, as far as most members were concerned, the union was reduced to a hiring hall.

The 1980s marked the total decline and fall of the Ship Scalers Union. In 1980, another reform candidacy was attempted when Bob Barnes, a younger, white member of the union, convinced Hearde to run again. Together they ran for the respective positions of secretary treasurer and business agent on a platform of reform, arguing it was poor accounting to have the positions combined. These claims were not unfounded. A 1979 audit of the union’s financial records revealed $13,750.78 missing from Harrison’s books and union funds.[77] Eventually the union was reimbursed for the missing funds by the corporation which bonded with Harrison and produced a check specifically noted “for loss caused by Van Harrison.”[78] Together Heard and Barnes advocated for change in the union’s internal affairs by calling for more accountability. Again, their election was contested by the LIUNA-backed Harrison and began a six-year battle of court cases in which the SSU continued to seek more independence from LIUNA, which was having its own international officers indicted on racketeering charges in Washington D. C.[79] The series of court cases brought the union into further financial despair, and paired with the economic troubles in Seattle industries in the 80s, directly contributed to the end of the union.

In 1980, the union listed a total of 837 members with roughly ninety percent of them working, but by 1986, The Seattle Post-Intelligencer noted that membership dropped by a third “to 550, with less than half working.”[80] Waning membership and hard economic times caused the union to fall behind in payments to various creditors as well as LIUNA, who said that Local 541 stopped paying dues in 1984. Finally in May of 1986, LIUNA suspended Local 541 for “failing to pay $60,000 in affiliation fees and pension contributions” and for owing upwards of $135,000 to its creditors.[81] In April, 1986, Oscar Hearde published the article, “An urgent appeal to Seattle Citizens for help” in The Facts, a Central District progressive newspaper. In it, Hearde attributed the union’s financial failures of the union specifically to the “Reagan Administration,” arguing that Reagan “failed to send enough work to the shipyards in the Northwest to supply the work necessary to keep our membership employed.”[82] The appeal was to raise money to keep the SSU in Seattle, but ultimately the union was forced to sell its E. Madison headquarters to pay their debts and control of the union was subsequently transferred to Local 252 in Tacoma.[83] Despite its lackluster finale, the Ship Scalers Union was dissolved amid controversy that existed since the union’s founding in the mid-1930s. In his appeal, Hearde wrote that the Ship Scalers Union possessed “a long history of being the most integrated, industrial Union of the Northwest,” and it is “one of the only Unions in the Northwest willing to stand up for the rights of our membership against what we consider to be the dictatorial powers of the International.”[84]

Conclusion: Pablo O’Higgins Mural and Martin Luther King Jr. Way

Despite Local 541’s shortcomings in its later years as a financial institution, it managed to leave a lasting impression on the soul of Seattle’s civil rights movement and in the corpus of the city. According to Del Castle, the early years of the union were led by idealists and was among the first to “challenge housing discrimination and prompted the first lunch-counter ‘sit-ins’ in the city.”[85] Beyond these policy and social changes though, there are two highly recognizable and visible physical remnants of the SSU’s impact in Seattle: A commissioned mural which still hangs in the city and the changing of a street name which runs through Seattle’s Central District.

1945 perhaps marked the highest union accomplishment in their involvement with the national dialogue. Mexican muralist Pablo O’Higgins agreed to paint a mural depicting the SSU’s history as a strongly anti-racist, anti-discriminatory, and progressive force in social politics. O’Higgins was in Seattle on the invitation of a University of Washington faculty member to give a visiting workshop on fresco painting at the university. Union officials who were familiar with his fresco work in Mexico approached him and asked him to do a mural for the auditorium of their Belltown union hall. According to O’Higgins, “It will portray the struggle against racial discrimination and the unity of international labor as one of the most important developments for future peace.”[86] O’Higgins solicited opinions from members of the union about what should be included in the mural and “for three weeks before I even planned this mural… I went out to the shipyards and talked to the workers—got their ideas and suggestions as to what they would like.”[87] Del Castle himself is portrayed in the mural in the lower right-hand corner, “whimsically” sporting a hammer and sickle on his lapel (see Figure 7).[88]

The 58-foot, thirteen-panel mural marked the peak of the union’s involvement and its history in many ways parallels the history of the SSU. When the union was forced to move out of Belltown in 1959, the mural was donated to the University of Washington and lost until February of 1975, when it was discovered in an outdoor storage area on the university’s campus. After a series of ownership disputes that lasted until 1977, the mural was to be placed at the Chicano cultural center El Centro de la Raza in Beacon Hill. The transfer would be effected once El Centro could raise enough money to have the panels transported there and ensure preservation safety in their building. Until then, the mural was to hang in Kane Hall, the main auditorium building at the University of Washington. The agreement between the University of Washington and El Centro was that the UW would pay for restoration costs, and El Centro would pay for transportation and new fixtures for their building.[89] It seems that El Centro did not raise enough money as the mural is still hanging today on the second floor of Kane Hall on the university’s campus. The mural itself depicts the SSU at its most active period of history and is representative of the SSU’s social involvement and publicity by containing, according to Clever, “all the clichés and idealized visions of the revolution that Castle and others had hoped would spread to American shores.”[90] That the mural remains visible to the public today is a testament to the Ship Scalers Union early and militant social commitment.

The final bout of the Ship Scalers Union came in 1982 with the city-wide controversy over the change in name of Seattle’s Empire Way to Martin Luther King Jr. Way. The Ship Scalers Union was central to the organization boycotting Empire Way stores that opposed the name change and ultimately proved successful for signing the bill into law. In the summer of 1982, the Seattle City Council approved a motion to change the name of Empire Way, a major South End and Central District arterial. The vote was cast and the name change would be signed into law and take effect later that year. In between the council vote and signing it into law, many merchants on the eight-mile stretch of road formed the Empire Way Merchants’ Association in protest and lobbied the city not to change the name on the grounds of the financial burdens it would cause the stores to change their stationary and signs, and the city to change its street signs.

In direct response to the Association, many Central District residents formed the Coalition for Respect and began boycotting Association stores. The Ship Scalers Union acted as liaison of the Coalition, issuing press releases, flyers, and aiding in organizing boycotts.[91] The contention over MLK Way was one of the most important local issues of the 80s, in part because it affected so many merchants, but primarily because of what it revealed about Seattle’s racial myopia. In fact, violence began at one boycott in early September, 1982 when patrons and the owner of the Empire Way Tavern began verbally harassing picketers. According to a Coalition press release in The Facts, “the tavern owner shouted racist insults, made other threatening and argumentative remarks, and pushed one African American woman. She then punched a white male picketer in the face, knocking off his glasses, and called him a ‘White nigger.’”[92] While the rhetoric was more tempered by the Coalition, their charges were not insubstantial. In one SSU flyer, the union argued, “It really gets down to some people just not wanting a street in front of their place named after a Black man…. This attitude, which is at the root of the movement to block the name change, displays a total lack of sensitivity to the fact that much of the money these merchants take is from Blacks and others who Dr. King spoke for.”[93] Eventually, the bill was signed into law and the street was renamed, though it is doubtful such a victory was possible without the aid of the Coalition for Respect and the Ship Scalers Union’s resurgent activism amid the city’s growing complacency regarding discrimination.

Through its periods of advocacy, the union seemed to maintain sight of its original values, preserving that rhetoric in all progressive stances it took. In the end, the union was unable to make a comeback from years of mismanagement and its disputes with LIUNA, but Local 541 of the Ship Scalers Union presented Seattle with a challenge to change its atrophied stance toward race relations during its effectual fifty-year history. Through its militancy and progressive voices, the SSU contributed to a lasting alteration of Seattle’s racial climate. The union’s activism signifies something beyond the gestalt of its members; it highlights the racial struggles Seattle and the nation underwent throughout the 20th century and causes a re-evaluated imagining of Seattle’s progressivism. Even though the Ship Scalers Union itself was neglected in its later years by its international, the SSU continued to subvert Seattle’s refusal to acknowledge its own minority residents.

© Copyright Adam Farley 2011

HSTAA 498D Winter 2010

[1] The Ship Scalers Union changed affiliation in 1956 to the Hod Carriers’ and Building Laborers’ Union of America (AFL) and became Local 541. Prior to 1956, they were affiliated with the International Brotherhood of Boilermakers Iron Ship Builders, Blacksmiths, Forgers and Helpers (AFL) as Local 589. This topic will be covered in greater detail later in the paper. For consistency, I will use Local 541throughout, except in citations which refer specifically to Local 589

[2] “Local Union 541 Constitution,” Biographical Features, Ship Scalers, Dry Dock, and Miscellaneous Boat yard Workers Union Records, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc # 4571-001, Box 1. Population figures: Quintard Taylor, The Forging of a Black Community (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1994), 160-192.

[3] Quoted in Bruce Nelson, “The ‘Lords of the Docks’ Reconsidered: Race Relations among West Coast Longshoremen, 1933-1961.” Waterfront Workers, edited by Calvin Winslow (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1998), 165.

[4] Philip S. Foner, Organized Labor and the Black Worker 1619-1973 (New York: Praeger Publishers, Inc., 1974), 247.

[5] In Local 13 specifically, Bruce Nelson writes “In January 1945, according to a ‘rough estimate’ by the local union president, the ‘number of Negro workers in Local 13’ was ‘between 400 and 500’—or less than 10 percent of a workforce that had more than doubled since the war began.” Nelson, “Lords of the Dock,” 164.

[6] Ibid., 165; Scaler’s News, “Protection of Foreign Born,” May, 1942, 2, George E. Flood Records, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc # 911-001, Box 1.

[7] Dick Clever, “Ship Scalers: A union’s half century of turmoil, tragedy and triumph,” The Seattle Times Pacific Magazine, May 2, 1982,6- 8.

[8] Ibid. For additional information regarding Seattle’s racial history, see Dana Frank’s study of Prohibition Era Seattle labor in “Race Relations and the Seattle Labor Movement,” Pacific Northwest Quarterly 86, no. 1 (1995): 35-44, and Quintard Taylor’s book, The Forging of a Black Community.

[9] Nelson, “Lords of the Dock,” 158.

[10] Quoted in Nelson, 158.

[11] Quintard Taylor. The Forging of a Black Community: Seattle’s Central District from 1870 through the Civil Rights Era (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1994), 159.

[12] Larry Richardson, “Civil Rights in Seattle: A Rhetorical Analysis of a Social Movement” (PhD diss., Washington State University, 1975), 32.

[13] Taylor, Forging, 161.

[14] Ibid., 166.

[15] Quoted in Nelson, 165.

[16] Scaler’s News, “Shop Steward’s Report on the Associated Shipbuilders Yard,” October 20, 1941, 4, George E. Flood Records, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc # 911-001, Box 1.

[17] Clever, “Ship Scalers,” 8.

[18] Ibid., 173.

[19] Scaler’s News, “Extra Work,” May, 1942, 1, George E. Flood Records, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc # 911-001, Box 1.

[20] Scaler’s News, December, 1941, 1, George E. Flood Records, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc # 911-001, Box 1.

[21] James G. Thompson, “Should I Sacrifice to Life ‘Half-American?,’” Pittsburg Courier, January 31, 1942, 3.

[22] Ibid., 4.

[23] Scaler’s News, “Extra Work,” 1.

[24] Quoted in The Seattle Times, “State Labor Raps Hecklers,” July 20, 1944, 5.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Clever, “Ship Scalers,” 14.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Membership Applications, Ship Scalers, Dry Dock, and Miscellaneous Boat yard Workers Union Records, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc # 4571-001, Box 3.

[29] University of Washington Libraries, “Guide to the Hugh DeLacy Papers,” Archival Finding Aids, http://www.lib.washington.edu/specialcoll/findaids/docs/papersrecords/DeLacyHugh3915.xml.

[30] The Seattle Times, “De Lacy Assumes Ship-Scaler Duties,” August 14, 1940, 4.

[31] Taylor, Forging, 182.

[32] University of Washington Libraries, “Guide to the Hugh DeLacey Papers.”

[33] The Seattle Times, “Ship Workers Elect Matheny,” February 1, 1940, 14.

[34] Scaler’s News, “Protection of Foreign Born.”

[35] The Seattle Times, “Fair Practices bill rejected,” March 19, 1946, 12.

[36] Taylor, Forging, 184.

[37] Seattle Inter-Racial Action Committee letter to Ship Scalers Union, September 24, 1946, General Correspondences, Ship Scalers, Dry Dock, and Miscellaneous Boat yard Workers Union Records, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc # 4571-001, Box 1.

[38] Clever, “Ship Scalers,” 8.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Original Emphasis. Scaler’s News, “Auxiliary News,” May, 1942, 3.

[41] Clever, “Ship Scalers,” 8.

[42] Castle was replaced by a politically conservative man named Leo Doyle, who had previously been the union’s president. Castle left union politics, focusing on Communist party issues, until his disillusionment with the party in 1956. Castle found it difficult to get work as a known communist and reported coming under such close surveillance by the FBI that they were on first-name basis with their assigned investigative agent. Ibid., 10.

[43] The Seattle Times, “A.F.L. will not be in parade,” August 30, 1946, 8.

[44] The Seattle Times, “Gerhard Eisler’s wife to speak here,” March 31, 1947, 14. “Mrs Eisler barred from Moose Hall,” April 1, 1947, 3. “Eisler’s Wife Gets Funds,” April 3, 1947, 4.

[45] The Seattle Times, “War Fund Asked at Lenin Rally,” February 6, 1948, 4.

[46] The Seattle Times, “CIO Council Convention to Open Tomorrow,” October 20, 1949, 51.

[47] The Seattle Times, “Public Protest Rally (Paid Advertisement),” October 19, 1949, 13.

[48] The Seattle Times, “Attorney for Reds to Speak in Seattle,” February 27, 1950, 10.

[49] The Seattle Times, “Founder to Speak,” June 6, 1951, 5. Clever also mentions the W.E.B. Du Bois lecture in his article.

[50] The Seattle Times, “Last Time Tonight: The Film of 1952,” March 13, 1952. 45.

[51] Clever, “Ship Scalers,” 6.

[52] There is some foundation for this fear, given the Ship Scalers’ involvement with both social issues. The primary fear however, was not the pairing of the two because the NAACP and other more conservative organizations despised communism per se, but that civil rights reform could not be taken seriously or be effected if it was associated with generally unaccepted politics and radicalism. Taylor, Forging, 184.

[53] Quoted in Taylor, 182.

[54] Clever, “Ship Scalers,” 14.

[55] Ship Scalers General Meeting Minutes, March 10, 1956, Ship Scalers, Dry Dock, and Miscellaneous Boat yard Workers Union Records, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc # 4571-001, Box 1.

[56] The Seattle Times, “Labor Unions, Social Reform to be Topics,” November 6, 1965, 16.

[57] The Seattle Times, “Antipoverty Board Off on ‘One Wing,’” November 16, 1964, 31.

[58] Taylor, Forging, 193.

[59] Ibid., 190.

[60] Ibid., 191.

[61] The Seattle Times, “Lockheed Shipscalers Walk Off Job,” August 25, 1966, 11. “Scalers, Lockheed in Agreement,” August 27, 1966, 7.

[62] The Seattle Times, “Walkout at Lockheed,” January 3, 1968, 52.

[63] The Seattle Times, “Scalers Back to Work at Lockheed,” January 9, 1968, 7.

[64] The Seattle Times, “Scalers in Walkout at Lockheed,” October 26, 1972, 47. “Lockheed Shipscalers Stay off Job,” October 27, 1972, 29. “Some Lockheed shipscalers return to work,” October 28, 1972, 26.

[65] The Hod Carriers changed their name in the mid-1960s and became what is still today the Laborers’ International Union of North America. When referring to the Hod Carriers it is when I am referencing events prior to the name change, LIUNA for events after the 60s.

[66] Clever, “Ship Scalers,” 18.

[67] Application for Charter to the International Hod Carriers’, Building and Common Laborers’ Union of America, (AFL), Biographical Information, Ship Scalers, Dry Dock, and Miscellaneous Boat yard Workers Union Records, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc # 4571-001, Box1.

[68] Executive Board Meeting, Minutes, March 17, 1959, Ship Scalers, Dry Dock, and Miscellaneous Boat yard Workers Union Records, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc # 4571-001, Box 1.

[69] Constitution for the International Hod Carriers’, Building and Common Laborers’ Union of America, Organizational Features, Ship Scalers, Dry Dock, and Miscellaneous Boat yard Workers Union Records, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc # 4571-001, Box 1.

[70] Taylor, Forging, 176. Some more specific discriminatory practices of the IBB can be found in Foner, Organized Labor and the Black Worker, 247-250.

[71] J.T. Thorpe & Son, Inc. to Ship Scalers & Drydock & Boat Yard Workers Union, February 4, 1955, General Correspondence, Ship Scalers, Dry Dock, and Miscellaneous Boat yard Workers Union Records, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc # 4571-001, Box1.

[72] Hod Carriers to Ship Scalers Local 589, March 3, 1958, General Correspondence, Ship Scalers, Dry Dock, and Miscellaneous Boat yard Workers Union Records, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc # 4571-001, Box1.

[73] Clever, “Ship Scalers,” 18.

[74] Clever, “Ship Scalers,” 16.

[75] According to Oscar Hearde, Harrison claimed “that the receipts ere stolen from him three different years in a row, 1969, 1970, and 1971.” Ibid., 18.

[76] Ibid., 16.

[77] Dick Clever, “Shipyard local rebels against international office,” U.S. News and World Report, August 31, 1981.

[78] Labor News, “Seattle Laborers Seek Injunction Against International’s Interference,” October 27, 1981, 5.

[79] Ed Barnes and Bob Windrem, “Six Ways to Take Over a Union,” Mother Jones, August, 1980, 34.

[80] List of Union Members, 1980, Membership Rolls, Ship Scalers, Dry Dock, and Miscellaneous Boat yard Workers Union Records, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc # 4571-001, Box 5. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer, “Union Suspends Ship Scaler’s Local,” May 8, 1986, News Articles, Ship Scalers, Dry Dock, and Miscellaneous Boat yard Workers Union Records, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc # 4571-001, Box 5.

[81] The Seattle Times, May 1, 1986, News Articles, Ship Scalers, Dry Dock, and Miscellaneous Boat yard Workers Union Records, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc # 4571-001, Box 5.

[82] Oscar Hearde and Ester Hearde, “An Urgent Appeal to Seattle Citizens for Help,” The Facts, April 30, 1986.

[83] Deed of Sale, June 6, 1986, Ship Scalers, Dry Dock, and Miscellaneous Boat yard Workers Union Records, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc # 4571-001, Box 5.

[84] Hearde, “An Urgent Appeal.”

[85] Quoted in Clever, 10.

[86] Quoted in The Seattle Times, “Artistic Work for Workmen,” August 5, 1945, 12.

[87] Ibid.

[88] Clever, “Ship Scalers,” 10.

[89] The Seattle Times Tempo, “Mexican muralist honored at U.W.,” October 24, 1975, 2. The Seattle Times, “Back In Sight,” August 20, 1977, A7.

[90] Clever, “Ship Scalers,” 10.

[91] Lee Moriwaki, “Fliers urge Boycott of Empire Way name-changing foes,” The Seattle Times, August 19, 1982, B1.

[92] Coalition for Respect Press Release, “Coalition for Respect Picketers Attacked—Seattle, Police Respond ‘Slowly’!,” The Facts, September 8, 1982, Letter to Reginald Johnson from Larry Meyers, Ship Scalers, Dry Dock, and Miscellaneous Boat yard Workers Union Records, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc # 4571-001, Box 5.

[93] Letter to Reginald Johnson from Larry Meyers, Ship Scalers, Dry Dock, and Miscellaneous Boat yard Workers Union Records, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc # 4571-001, Box 5.