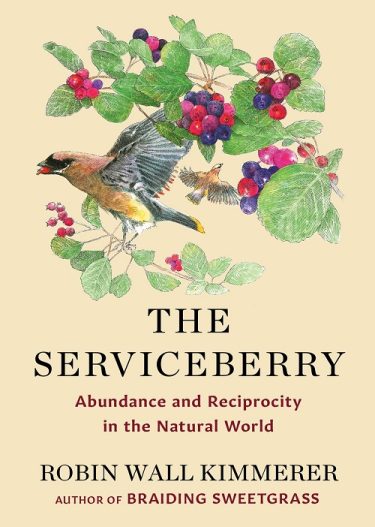

The Serviceberry tree lives in a reciprocal relationship with its environment – it takes only what it needs to grow and gives its fruit abundantly. Robin Wall Kimmerer uses the plant, especially in its Native American context, as a model for the gift economy she argues we must create.

Kimmerer’s Serviceberry is a western species, Amelanchier alnifolia, which is good to eat, unlike a common eastern variety, A. arborea. Indigenous groups use it many ways, as an important element of their diet. Readers may recognize the plant by one of its many other names: Saskatoon, Juneberry, Shadbush, Shadblow, Sugarplum and Sarvis. Kimmerer uses these alternatives as she writes.

After comparing the Northwest Native American potlatch, which involves much mutual gift giving, and other examples of Native American sharing to the economy she wants us to develop, Kimmerer admits that scaling the process up to a national or international practice has proven difficult or impossible. In the end she submits that even small scale “intentional communities of mutual self-reliance and reciprocity” provide benefits to the givers and receivers and to the natural world:

“The real human needs that such arrangements address are exactly what we long for yet cannot ever purchase: being valued for your own unique gifts, earning the regard of your neighbors for the quality of your character, not the quantity of your possessions; what you give, not what you have” (p. 92).

The Serviceberry makes a good case on its own. It is even more effective as a follow-up to Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass, a fuller account of the interdependence of humans and nature. Read them both.

Reviewed by Priscilla Grundy in The Leaflet, Volume 12, Issue 5, May 2025.

The Serviceberry tree lives in a reciprocal relationship with its environment – it takes only what it needs to grow and gives its fruit abundantly. Robin Wall Kimmerer uses the plant, especially in its Native American context, as a model for the gift economy she argues we must create.

The Serviceberry tree lives in a reciprocal relationship with its environment – it takes only what it needs to grow and gives its fruit abundantly. Robin Wall Kimmerer uses the plant, especially in its Native American context, as a model for the gift economy she argues we must create.