We recently bought a house on San Juan Island with lots of beautiful madronas (Arbutus menziesii) on the property. Two of them show no signs of life… others have the occasional dead branch here and there. We have been advised that this is likely caused by a fungus and that it can spread rapidly. We have been shown blackened excavated areas on the trunks of the dead trees.. and similar though less extensive areas on some of the others. What can be done to save our beautiful madronas?

It is possible your trees are suffering from canker fungus (Nattrassia mangiferae), or some other type of fungal disease. Here is a link to a file called “The Decline of the Pacific Madrone” edited by A. B. Adams (from a symposium held here at the Center for Urban Horticulture in 1995).

You may want to call a certified arborist to look at the trees, determine the extent of the disease, and help you decide whether the trees can be salvaged. (Search the Pacific Northwest Chapter of the International Society of Arboriculture for a local arborist.)

Below is a response to a question similar to yours from the

University of British Columbia Botanical Garden and Centre for Plant Research:

“What you describe are the classic symptoms of ‘Arbutus decline,’ which is postulated in the literature as being caused by mostly naturally-occurring, weakly pathogenic fungi, made more virulent by the predisposition of Arbutus to disease, caused by urban stresses, especially root disturbance.” (see also: “Arbutus Tree Decline” from Nanaimo. B.C.’s Parks, Recreation and Culture department)

Nevertheless, I am convinced that much of the die-back we are seeing on established Arbutus trees stems not from disease, but primarily from the complications of damage, competition, shading and especially, drought stress (we have had a run of very droughty summers). Typically, the most affected natural stands of Arbutus are very dense, with poor air-circulation, internal shading and intense competition for resources (characteristic of rapid growth after clearing). And because this region is becoming increasingly urbanized, with more vehicular and marine traffic (marine traffic evidently accounts for a huge proportion of the pollution in the Fraser Basin air-shed), I would not discount atmospheric pollution as a contributor to the decline (one more stress).

I think the reason your shaded trees are not as affected is that their roots are probably deeper and less exposed, and there is reduced evaporative demand on the leaves. However, as the shade increases, these plants, or at least their shaded branches, will succumb.

What to do? I do not think there is anything you can do to save the existing trees, except, perhaps, to minimize human influence around them. You should avoid both disrupting roots and damaging above-ground portions of the trees (with pruning, for example), as any wound is an open invitation to disease-causing micro-organisms. Interestingly, a friend of mine who kayaks has seen black bears foraging for fruit in the tops of Arbutus trees on Keats Island (he should have told them they are not helping the situation any).

Irrigation of established plants is nearly always counter-productive because it encourages surface rooting (which is typically short-lived and considerably less resilient than deep rooting), and summer irrigation is worse, as Arbutus are well adapted to our conditions (at least, where we find them growing naturally) and normally somewhat dormant in summer.

You can plant more Arbutus, as a previous correspondent in this thread has, to replace what you are losing, but there is no guarantee that these plants will survive the next drought or indeed, your well-intentioned meddling. (I suspect his plant was lost for the same reason most young Arbutus are lost–by root damage from saturated or compacted soil conditions). The natural succession on your island is probably (as elsewhere in similar places along the coast) tending toward open Douglas fir forest with a few scattered Arbutus in the more inhospitable places. In other words, you can plant what you will, but the larger the Douglas firs, the fewer Arbutus will be able to survive around them. Neither species is particularly shade tolerant and resources are pretty limited on rocky ground, where both prefer to grow locally. Expect change.

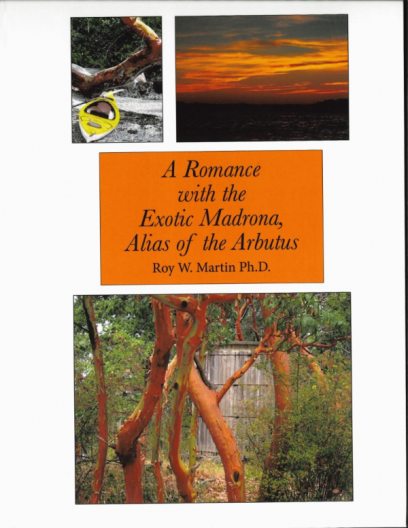

Roy Martin is a retired University of Washington professor of anesthesiology and bioengineering. He is now pursuing a very different passion, the genus Arbutus, best known locally by A. menziesii, the Pacific Madrone. Eleven species are recognized and in “A Romance with the Exotic Madrona, Alias of the Arbutus,” Martin explores them all, visiting their native ranges in Mexico, western North America, and around the Mediterranean.

Roy Martin is a retired University of Washington professor of anesthesiology and bioengineering. He is now pursuing a very different passion, the genus Arbutus, best known locally by A. menziesii, the Pacific Madrone. Eleven species are recognized and in “A Romance with the Exotic Madrona, Alias of the Arbutus,” Martin explores them all, visiting their native ranges in Mexico, western North America, and around the Mediterranean.