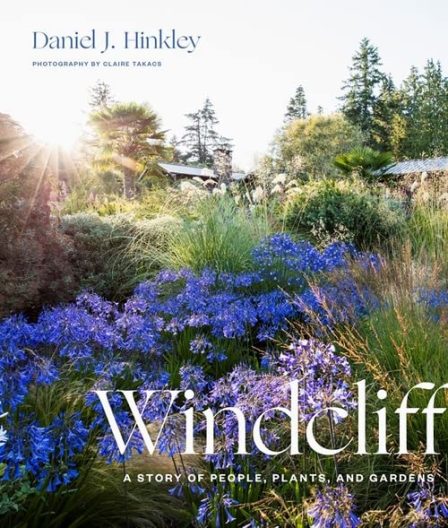

Dan Hinkley newest book, “Windcliff: A Story of People, Plants, and Gardens,” is largely about that garden, his residence of the last 20 years with his husband, Robert Jones. As hinted at in the sub-title, the book is also a memoir about Hinkley’s youth in a small, Michigan town and the world-wide network of friends and colleagues he has developed through horticulture and plant exploration.

Dan Hinkley newest book, “Windcliff: A Story of People, Plants, and Gardens,” is largely about that garden, his residence of the last 20 years with his husband, Robert Jones. As hinted at in the sub-title, the book is also a memoir about Hinkley’s youth in a small, Michigan town and the world-wide network of friends and colleagues he has developed through horticulture and plant exploration.

Windcliff is divided into several broad areas based on the types of plantings, and Hinkley uses these areas as a structure for the book. Both endpapers show a helpful plan of the property to help you keep track. Within each chapter, a series of essays explore specific plantings, design challenges and solutions, and an intimate view into the various successes and failures, often with correlations to the author’s personal life.

My impression of the book is shaped by a handful of visits I’ve made to Windcliff, with my most vivid memories being of the bluff. Not surprisingly, this is the centerpiece of the book. A large open space with vast views is very different from the garden at Heronswood where Hinkley and Jones lived previously. The design challenges were equally immense, but they pulled it off magnificently.

The photography of Claire Takacs well captures the feeling of the bluff and its plantings, while the writing explains the why and how those plantings in that space were achieved. I found the essays on the large grasses, the agapanthus, and other South African natives especially engaging.

While the bluff was an unqualified success, the meadow near the entry drive was not. As gardeners, the most fun is to read about another’s failures, especially by an eminent plantsperson such as Hinkley. In brief, he discovered that his deepest affinity is with woody plants, and so an arboretum of trees and shrubs, many found on his plant exploration trips, are gradually taking over the meadow.

Other setbacks, such as a neighbor’s large, ugly house on the property line, will also resonate with readers, but so will the re-discovery of the joys of a vegetable garden. Gardeners without vast acreage will find value in the extensive section on potted plants placed near the house. After reading that chapter, I will definitely try Eucomis in a container this year.

The area around the house is where the visions of Hinkley and architect Jones intersect. The give-and-take will amuse and inform couples that have a similar dynamic. Throughout the writing, Hinkley’s wry sense of humor and deep sensibilities of the emotional importance of gardens is very clear. “There are more approaches, more tricks to the trade, undoubtedly as many as there are good gardeners. Yet the yearning for beauty, whatever that may be, is the same. It is not intentional nor is it fully accidental. There is no endpoint or possession.”

Excerpted from the Spring 2021 issue of the Arboretum Bulletin

If your garden doesn’t have much space for growing herbs, a container garden might be the answer. I recommend a new book on this topic by western Washington writer, Sue Goetz.

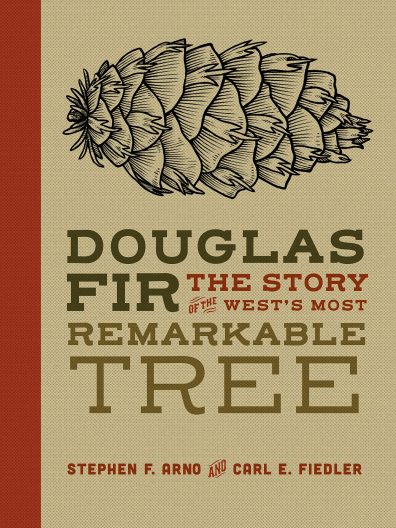

If your garden doesn’t have much space for growing herbs, a container garden might be the answer. I recommend a new book on this topic by western Washington writer, Sue Goetz. There are many rare and unusual trees and shrubs in the Washington Park Arboretum. Standing aside (and sometimes out-competing) these wonderful exotics is the native matrix of trees, especially tall conifers. Perhaps the most iconic of these is the Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii). “Douglas Fir: The Story of the West’s Most Remarkable Tree” is a comprehensive new book by Stephen Arno and Carl Fiedler about this tree native from northern British Columbia to the high mountains of Mexico.

There are many rare and unusual trees and shrubs in the Washington Park Arboretum. Standing aside (and sometimes out-competing) these wonderful exotics is the native matrix of trees, especially tall conifers. Perhaps the most iconic of these is the Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii). “Douglas Fir: The Story of the West’s Most Remarkable Tree” is a comprehensive new book by Stephen Arno and Carl Fiedler about this tree native from northern British Columbia to the high mountains of Mexico.![[Braiding Sweetgrass] cover](https://depts.washington.edu/hortlib/graphix/braidingsweetgrass300.jpg)

![[The Sakura Obsession] cover](https://depts.washington.edu/hortlib/graphix/sakuraobsession300.jpg)

![[Nature Obscura] cover](https://depts.washington.edu/hortlib/graphix/natureobscura300.jpg)

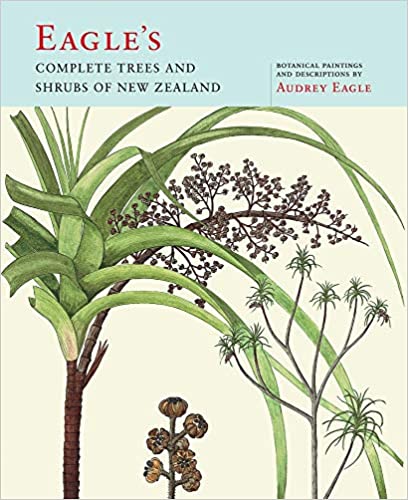

Audrey Lily Eagle (born 1925) was born in New Zealand, but spent her adolescent years in Oxfordshire, England. There she learned a love of plants and began to draw and paint them. She also took training in engineering drafting, a skill that is apparent in the precision of her later work. When she returned to New Zealand, it became her passion to illustrate almost all of the woody flora of New Zealand, “over 800 species, subspecies, and unnamed plants. It is assumed that the number of any new finds is certain to be small.”

Audrey Lily Eagle (born 1925) was born in New Zealand, but spent her adolescent years in Oxfordshire, England. There she learned a love of plants and began to draw and paint them. She also took training in engineering drafting, a skill that is apparent in the precision of her later work. When she returned to New Zealand, it became her passion to illustrate almost all of the woody flora of New Zealand, “over 800 species, subspecies, and unnamed plants. It is assumed that the number of any new finds is certain to be small.” Emily Carr (1871-1945) was a native of Victoria, British Columbia and lived much of her life in that city. She is best known as a painter, but was also an accomplished writer. Many of her works in both disciplines reflected her passionate interest in the indigenous peoples of Vancouver Island and other parts of British Columbia.

Emily Carr (1871-1945) was a native of Victoria, British Columbia and lived much of her life in that city. She is best known as a painter, but was also an accomplished writer. Many of her works in both disciplines reflected her passionate interest in the indigenous peoples of Vancouver Island and other parts of British Columbia. Margaret Stones (1920-2018) was born in Australia but spent much of her career in Britain. She was the principal contributing artist to Curtis’s Botanical Magazine from 1958-1981 and illustrated three gardening books by the Scottish plant explorer E. U. M. Cox and his son Peter Cox in the 1950s and 1960s. She is perhaps most famous for illustrating the six-volume “The Endemic Flora of Tasmania” published between 1967 and 1978.

Margaret Stones (1920-2018) was born in Australia but spent much of her career in Britain. She was the principal contributing artist to Curtis’s Botanical Magazine from 1958-1981 and illustrated three gardening books by the Scottish plant explorer E. U. M. Cox and his son Peter Cox in the 1950s and 1960s. She is perhaps most famous for illustrating the six-volume “The Endemic Flora of Tasmania” published between 1967 and 1978. “I am glad that the month of October 1970 has been assigned to us for displaying the original artwork for The Endemic Flora of Tasmania.” This is the beginning of a letter written in December 1969 to Brian O. Mulligan, the Director of what was known then as the University of Washington Arboretum. The writer was Robert D. Monroe, the Chief of Special Collections Division of the University Library (now University Libraries) which would host the exhibit in the Smith Room of Suzzallo Library.

“I am glad that the month of October 1970 has been assigned to us for displaying the original artwork for The Endemic Flora of Tasmania.” This is the beginning of a letter written in December 1969 to Brian O. Mulligan, the Director of what was known then as the University of Washington Arboretum. The writer was Robert D. Monroe, the Chief of Special Collections Division of the University Library (now University Libraries) which would host the exhibit in the Smith Room of Suzzallo Library.