Jennifer Jewell has gained a wide following for her blog “Cultivating Place.” Produced from her home in northern California, it is self-described as a “conversation on natural history & the human impulse to garden.”

Jennifer Jewell has gained a wide following for her blog “Cultivating Place.” Produced from her home in northern California, it is self-described as a “conversation on natural history & the human impulse to garden.”

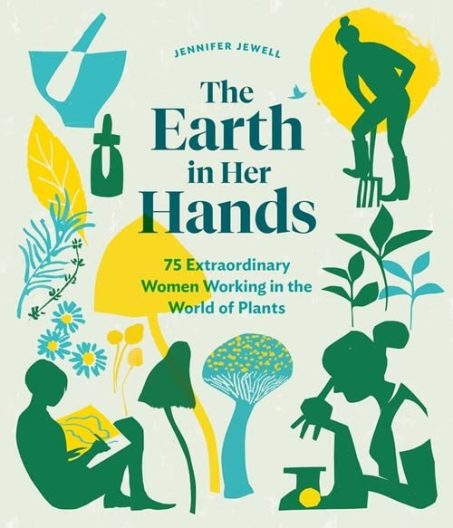

That same description could apply in part to Jewell’s first book, “The Earth in Her Hands: 75 Extraordinary Women Working in the World of Plants.” This is a wide-ranging discussion on this gardening impulse, using a very broad definition of the idea of horticulture, captured in a series of pithy biographies. The profiled women have careers in and a passion for plants, expressed in botany, landscape architecture, floriculture, agriculture, plant hunting and breeding, food justice, garden writing, and photography.

Many of the subjects are from the Pacific Northwest. An example is Cara Loriz, the executive director of the Organic Seed Alliance in Port Townsend, Washington, advocating for community building and research for sustainable food systems.

Another is Christin Geall, a multi-talented writer/photographer and educator in Victoria, British Columbia. I confess to having not heard of either woman prior to reading this book. Jewell writes that for Geall, “flowers are a horticultural medium for leading and educating others about plants, acting not as pretty cages, but as colorful, Socratic-style critical thinking.” Both women are examples of conducting important work at a local level that addresses global needs facing all cultures.

All these biographies provide a short list of women that inspired the subject. Many are contemporaries, or cherished ancestors. Some are important figures from history, including Sacajawea, Harriet Tubman, and Rachel Carson. Others are women without recorded names, but for whom “horticulture is a human impulse, in all cultures, in all times, practiced, codified, ritualized, and valued across any and all social boundaries.”

The narratives about women in horticulture are evolving. In public presentations, Jewell has been expanding on the process of choosing and researching the subjects of her book. I’ve heard her speak twice in the last year and each time, she acknowledges that many additional women, from a wider breadth of ethnicities and nationalities, could be featured now. This study is important, on-going work and I hope that Jewell or others will continue this undertaking.

Winner of the 2021 Award of Excellence in Biography from the Council on Botanical and Horticultural Libraries

Excerpted from the Summer 2021 issue of the Arboretum Bulletin

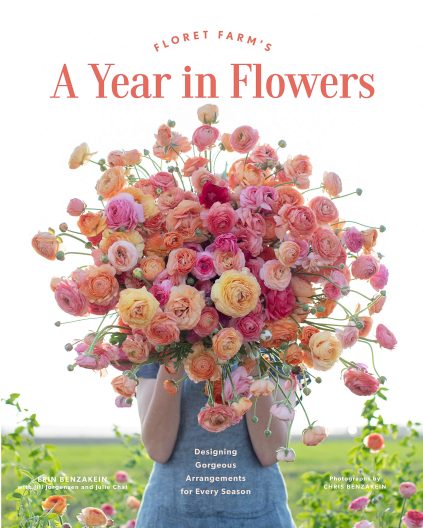

“Floret Farm’s A Year in Flowers”, is an especially helpful book on flower arranging for those who prefer a structured teaching approach and lots of practical matters, along with inspiration. To do this, Erin Benzakein and her co-authors use many comparison photographs.

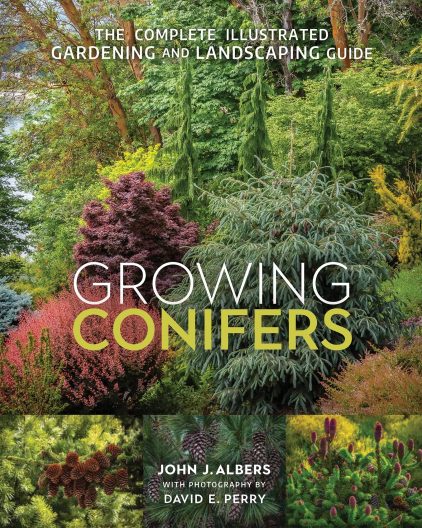

“Floret Farm’s A Year in Flowers”, is an especially helpful book on flower arranging for those who prefer a structured teaching approach and lots of practical matters, along with inspiration. To do this, Erin Benzakein and her co-authors use many comparison photographs. John Albers has highlighted his garden of 20 years in Bremerton and his passion for sustainable gardening practices in two previous books. Now, he turns his attention to a favorite plant group: conifers, especially dwarf and small cultivars. He is very clear in his reasons for writing the book. “Given the horticultural and ecological importance of urban conifers, it is vital that all of us do our part to restore conifers to our urban environment.”

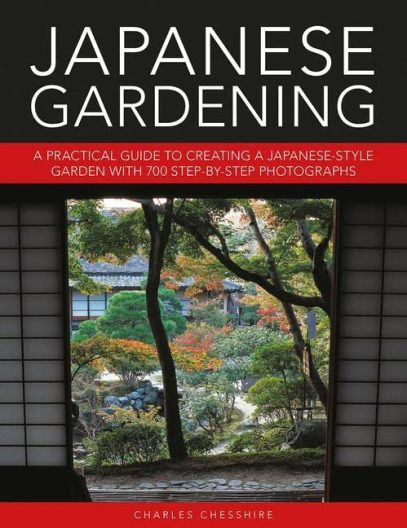

John Albers has highlighted his garden of 20 years in Bremerton and his passion for sustainable gardening practices in two previous books. Now, he turns his attention to a favorite plant group: conifers, especially dwarf and small cultivars. He is very clear in his reasons for writing the book. “Given the horticultural and ecological importance of urban conifers, it is vital that all of us do our part to restore conifers to our urban environment.” “Japanese Gardening: A Practical Guide” provides a long-needed book on how to apply the principles of Japanese style gardens on a small scale, allowing the incorporation of Japanese garden elements in a home garden.

“Japanese Gardening: A Practical Guide” provides a long-needed book on how to apply the principles of Japanese style gardens on a small scale, allowing the incorporation of Japanese garden elements in a home garden.![[Around the World in 80 Plants] cover](https://depts.washington.edu/hortlib/graphix/aroundtheworldin80plants300.jpg)

![[book title] cover](https://depts.washington.edu/hortlib/graphix/theKinfolkgarden300.jpg)

![[Tokachi Millennium] cover](https://depts.washington.edu/hortlib/graphix/TokachiMilleniumForest300.jpg)

![[The Food Explorer] cover](https://depts.washington.edu/hortlib/graphix/foodexplorer300.jpg)

![[Under Western Skies] cover](https://depts.washington.edu/hortlib/graphix/underwesternskies300.jpg)

What is a Wardian Case? Any English gardener between 1850 and 1900 could have easily answered that question, but today it is mostly forgotten. Partly because the term was used for two distinct variations of the device. The first was a decorative, enclosed case – the forerunner to the terrarium – that allowed Victorian plant lovers to grow their ferns and orchids despite the heavily polluted air of London and other cities. The second was a tool for transporting plants on long sea voyages, and that form is the subject of “The Wardian Case: How a Simple Box Moved Plants and Changed the World” by Luke Keogh.

What is a Wardian Case? Any English gardener between 1850 and 1900 could have easily answered that question, but today it is mostly forgotten. Partly because the term was used for two distinct variations of the device. The first was a decorative, enclosed case – the forerunner to the terrarium – that allowed Victorian plant lovers to grow their ferns and orchids despite the heavily polluted air of London and other cities. The second was a tool for transporting plants on long sea voyages, and that form is the subject of “The Wardian Case: How a Simple Box Moved Plants and Changed the World” by Luke Keogh. Jennifer Jewell has gained a wide following for her blog “Cultivating Place.” Produced from her home in northern California, it is self-described as a “conversation on natural history & the human impulse to garden.”

Jennifer Jewell has gained a wide following for her blog “Cultivating Place.” Produced from her home in northern California, it is self-described as a “conversation on natural history & the human impulse to garden.”