Women’s History Month

To commemorate Women’s History Month, UW Medicine Healthcare Equity shares the following healthcare sector pioneers. While there are many women who contributed to the advancement of public health and medicine in our country, we chose to elevate some lesser known figures.

Helen Rodríguez-Trías, MD

Photo Credit: American Journal of Public Health

Dr. Helen Rodríguez-Trías was named the first Latina president of the American Public Health Association (APHA) in 1993. She pursued a career as a physician because medicine “combined the things I loved the most, science and people. I understood that medicine would give me more direct and independent ways to contribute to society, not through organizations or abstract studies, but acting directly on the individual.” Dr. Rodríguez-Trías was a founding member of the Women’s Caucus of the American Public Health Association, Committee for Abortion Rights and Against Sterilization Abuse. She received the Presidential Citizen’s Medal for her work on behalf of women, children, people with HIV and AIDS and the poor.

Having earned a medical degree from the University of Puerto Rico with the highest honors in 1960, established the first center in Puerto Rico for the care of newborn babies during her residency. Under Dr. Rodríguez-Trías’ leadership, the university’s hospital’s death rate for newborns decreased 50 percent within three years. In 1970, she returned to New York City to serve the South Bronx’s Puerto Rican residents. Working at Lincoln Hospital, she led community educational campaigns against lead paint, unprotected windows and other health hazards.

Dr. Rodríguez-Trías stated, “I think my sense of what was happening to people’s health… was that it was really determined by what was happening in society— by the degree of poverty and inequality you had.” Working as an advocate for women’s reproductive rights, she campaigned for change at a policy level. She worked especially for low-income populations in the United States, Central and South America, Africa, Asia, and the Middle East.

Government-sponsored sterilization programs led to hundreds of unwanted sterilizations – a human rights violation Dr. Rodríguez-Trías worked to end. She shared, “Sterilization has been pushed really internationally as a way of population control. And there is a difference between population control and birth control. Birth control exists as an individual right. It’s something that should be built into health programming. It should be part and parcel of choices that people have. And when birth control is really carried out, people are given information, and the facility to use different kinds of modalities of birth control. While population control is really a social policy that’s instituted with the thought in mind that there’s some people who should not have children or should have very few children, if any at all. I was working in Puerto Rico in the medical school in those years, the decade of 1960 to 1970. And one of the things that seemed pretty obvious to us then was that Puerto Rico was being used as a laboratory. And it was being used as a laboratory for the development of birth control technology.”

In 1979, Dr. Rodríguez-Trías testified before the Department of Health, Education and Welfare for the passage of federal sterilization guidelines, which she helped to draft. Her involvement in composing the guidelines epitomizing the importance of women having a seat at the proverbial table – having an opportunity to direct how healthcare policies are set. Because of her involvement, the guidelines require a woman’s consent to sterilization, offered in a language she can understand, and set a waiting period between the consent and the operation.

It is reported near the end of her life, Dr. Rodríguez-Trías said, “I hope I’ll see in my lifetime a growing realization that we are one world. And that no one is going to have quality of life unless we support everyone’s quality of life. Not on a basis of do-goodism, but because of a real commitment. It’s our collective and personal health that’s at stake.”

In 2001, President Clinton presented her with a Presidential Citizen’s Medal for her work on behalf of women, children, people with HIV and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), and the poor. Later that year, Dr. Rodríguez-Trías died of complications from cancer.

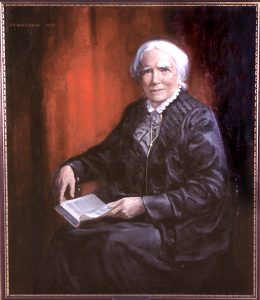

Elizabeth Blackwell, MD

Photo Credit: Amazing Women in History by Kerilynn Engel

Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell was the first woman to receive a medical degree (MD) from an American school of medicine. Dr. Blackwell and colleagues founded the New York Infirmary for Women and Children. Born in Bristol, England in 1821, her parents Hannah Lane and Samuel Blackwell moved to the United States when she was 11 years old. This journey across the Atlantic was driven by the promise of better economic opportunities for the Blackwell family as well as her father’s motivation to do his part in abolishing slavery. It is reported Dr. Blackwell pursued a career in medicine after a dear friend on her death bed shared she would have been spared her worst suffering if her physician had been a woman.

Given the lack of upward mobility afforded any individuals who were not white and male, Dr. Blackwell was fortunate enough to have two male friends – physicians – who allowed her to read their medical text. After a year of studying her friends’ resources, Dr. Blackwell applied for admission into every medical school in New York and Philadelphia. She submitted applications to 12 additional medical schools in other northeastern states. In 1847, Blackwell was granted admittance into the Geneva Medical College in western New York State. The faculty at Geneva Medical College allowed the all-male student body to vote whether Dr. Blackwell could matriculate. As a misogynistic joke, her future all-male cohort voted “yes,” and she gained admittance.

In 1849, Dr. Blackwell earned her medical degree. Afterwards, she worked in London and Paris clinics, studied midwifery at La Maternité. Dr. Emily Blackwell – her sister –and Dr. Marie Zakrzewska began collaborating in 1856. This partnership resulted in their founding the New York Infirmary for Women and Children at 64 Bleecker Street in 1857. This institution and its medical college opened in 1867 with a focus on educating women doctors as well as providing other training opportunities needed to care for the underserved.

To learn more about Dr. Blackwell’s journey, consider her Changing the Face of Medicine biography or a National Women’s History Museum write-up of her journey edited by Debra Michals, PhD.

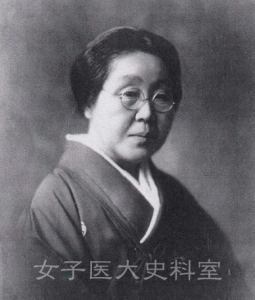

Yoshioka Yayoi, MD

Photo Credit: Prabook, World Biographical Encyclopedia, Inc.

The founder of Japan’s first medical school for women, Dr. Yayoi began working toward this achievement by margining her medical clinic – where she trained women students – with her husband’s German-language academy in 1900. This merger created the Tokyo Women’s Medical Institute which has the current day name Tokyo Women’s Medical University.

Among the first group of Japanese women to earn a professional status in the Land of the Rising Sun, Dr. Yayoi’s home became a makeshift center for young working professionals – especially women who sought her tutelage in navigating the journey to having professional careers.

Neither the Japanese government during this era nor society at large were particularly fond of Dr. Yayoi’s endeavors. Public outcry considered women working as doctors “grossly unladylike;” especially regarding scientific work such as dissecting cadavers. Dr. Yayoi vocalized her responses to these criticism via her institution’s newspaper, Joikai. More than 7,000 women were educated via the Tokyo Women’s Medical Institute during Dr. Yayoi’s 53-year tenure. Dr. Yayoi also operated Tokyo Shisei Byoin – a hospital – and played an active role in governmental organizations. In 1955, she was awarded the Fujin Bunka Sho, the highest award given to women in Japan.

To learn more about Dr. Yayoi, read Encyclopedia.com’s entry about her as well as a May 1959 New York Times article about Japan’s first woman physician.

Joycelyn Elders, MD

Photo Credit: Center for Sex Education

Dr. Joycelyn Elders was the first person in the state of Arkansas to become board certified in pediatric endocrinology. Appointed by then President William Jefferson Clinton, Dr. Elders became the first African American woman Surgeon General of the United States on September 10, 1993. She was also the first African American and second woman to head the United States Public Health Service.

After graduating from Philander Smith College in Little Rock, Arkansas and hearing a speech by Edith Irby Jones – the first African American student to attend the University of Arkansas School of Medicine, Dr. Elders decided to pursue a medical degree. Before she began medical school, Dr. Elders joined the Army and trained in physical therapy at the Brooke Army Medical Center at Fort Sam Houston, Texas.

To capitalize on her earning the G. I. Bill, Dr. Elders completed an internship in pediatrics at the University of Minnesota – returning to the University of Arkansas for her residency in 1961. After becoming chief resident, Dr. Elders directed all-white, all-male residents and interns. In 1967, she earned her master’s degree in biochemistry, became an assistant professor of pediatrics in 1971, and full professor in 1976.

Over the next twenty years, Dr. Elders merged her clinical practice with research in pediatric endocrinology. She published well over a hundred papers – most of which focused on issues related to growth and juvenile diabetes. This work directed Dr. Elders to study sexual behavior and adolescents’ advocacy work.

Governor Bill Clinton appointed Dr. Joycelyn Elders head of the Arkansas Department of Health in 1987. As a result of her diligent public health focus to elevate robust sexual education and vaccinations, the Arkansas Legislature mandated a K-12 curriculum that included sex education, substance-abuse prevention, and programs to promote self-esteem in 1989. From 1987 to 1992, she nearly doubled childhood immunizations, expanded the state’s prenatal care program, and increased home-care options for the chronically or terminally ill.

Clara Barton

Photo Credit: American Battlefield Trust

Barton risked her life to bring supplies and support to soldiers in the field during the Civil War. At age 60, she founded the American Red Cross in 1881 and led it for the next 23 years. Clara Barton was working as a recording clerk in the United States Patent Office in Washington, D.C. when the first units of federal troops poured into the city in 1861. To help treat the wounded soldiers, Barton began offering supplies to the young men of the Sixth Massachusetts Infantry.

Temporarily housed in the unfinished Capitol Building to recover, the Union soldiers had been attacked in Baltimore by individuals supportive of the Confederate States of America – those which had undergone succession from the United States of America in exercising their states right to uphold the institution of slavery. Besides supplies, Barton offered personal support to the men in hopes of keeping their spirits up: she read to them, wrote letters for them, listened to their personal problems, and prayed with them.

When Clara Barton visited Europe in search of rest in 1869, she ended up broadening her provision of service through the Red Cross in Geneva, Switzerland. In 1870 during the Franco-Prussian War, Barton once again decided to do her part in distributing relief supplies to the destitute in the conquered city of Strasbourg and elsewhere in France.

Once back in the United States, Barton kept in touch with Red Cross officials in Switzerland – who recognized her leadership abilities for including the United States in the global Red Cross network. With an endorsement letter from the head of the International Committee of the Red Cross, Barton took her appeal for the United States Government’s signing the Geneva Treaty to President Rutherford B. Hayes in 1877, but he looked on the treaty as a possible “entangling alliance” and rejected it. His successor, President James Garfield, was supportive and seemed ready to sign it when he was assassinated. Finally, Garfield’s successor, Chester Arthur, signed the treaty in 1882 and a few days later the Senate ratified it.

The American Red Cross received its first congressional charter in 1900. With Barton at its head, the American Red Cross was largely devoted to disaster relief for the first two decades of its existence. The Red Cross flag flew officially for the first time in the United States in 1881 when Barton issued a public appeal for funds and clothing to aid more than 14,000 victims of a devastating forest fire in Sanilac County, Michigan. In 1884, she and 50 volunteers arrived in Johnstown, PA to help the survivors of a dam break that caused over 2000 deaths.

To learn more about the Clara Barton’s work in founding the American Red Cross, click here. History also offers a review of Barton’s journey to founding the disaster relief organization.

Wafaa El-Sadr MD, MPH, MPA

Photo Credit: John D. & Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation

Wafaa El-Sadr, MD, MPH, MPA is a University Professor of Epidemiology and Medicine at Columbia University, founder and director of ICAP at Columbia University, and director of the Global Health Initiative at the Mailman School of Public Health.

ICAP is a global leader in the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), other global health threats, and health systems strengthening that provides technical assistance, implementation support, and conducts research in partnership with governmental and non-governmental organizations in more than 21 countries, accordingly to the Mailman School of Public Health. As the director of ICAP, Dr. El-Sadr leads the design, implementation, scale-up, and evaluation of large-scale HIV, tuberculosis and maternal-child health programs in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia. ICAP reaches over 2.2 million people on the two continents – providing access to HIV services and collected data from over 5,200 health facilities.

Dr. El-Sadr contribution to preventing and managing non-communicable diseases, HIV, and tuberculosis includes numerous epidemiological, clinical, behavioral, and implementation science research studies. She is a principal investigator of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) funded HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) – purposed with preventing HVI transmission globally.

Dr. El-Sadr is a member of the NIH Fogarty International Center Advisory Board. In 2008, she was named a John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Fellow, and in 2009, she was appointed to the National Academy of Medicine. In 2013, she was appointed University Professor, Columbia University’s highest academic honor. She also holds the Dr. Mathilde Krim-amfAR Chair in Global Health.

The Mailman School of Public Health at Columbia University provides a biography of Dr. El-Sadr as does the MacArthur Foundation.

Regina Benjamin, MD, MBA

Photo Credit: Changing the Face of Medicine

Dr. Regina Benjamin served as the 18th Surgeon General of the United States – oversaw 6,500 uniformed public health officers who held post across the globe in advancing and protecting the health of the American citizenry. As the first physician under the age of 40 and the first African American woman elected to the American Medical Association Board of Trustees in 1995, Dr. Benjamin is the former associate dean for Rural Health at the University Of South Alabama College Of Medicine in Mobile.

Dr. Benjamin founded a rural health clinic – BayouClinic – in Bayou La Batre, Alabama purposed with serving underserved Alabamians along the Yellowhammer State’s Gulf coast. Remarkably, Dr. Benjamin’s clinic survived damage inflicted by hurricanes Georges in 1998 and Katrina in 2005. The clinic also was damaged by a fire in 2006.

Dr. Benjamin was past chair of the Federation of State Medical Boards of the United States. She served as president of the American Medical Association Education and Research Foundation and chair of the AMA Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs. In 2002, she became the first African-American female president of a state medical society in the United States when she assumed leadership of the Medical Association State of Alabama.

Chartered under the 16th President of the United States – Abraham Lincoln – Dr. Benjamin is a member of the Institute of Medicine – the health arm of the National Academy of Sciences. She is a fellow of the American Academy of Family Physicians. She was chosen as a Kellogg National Fellow and a Rockefeller Next Generation Leader. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Catholic Health Association, and Morehouse School of Medicine are past board memberships held by Dr. Benjamin.

Named one of the “Nation’s 50 Future Leaders Age 40 and Under” by Time Magazine. Dr. Benjamin was featured in the 1995 New York Times article, “Angel in a White Coat;” the December 1999 cover of Clarity magazine; in the 2002 People magazine’s article, “Always on Call;” and was recognized on the January 2003 cover of Reader’s Digest as one of the national publication’s “Everyday Heroes.”

Accordingly to the New York Times, Dr. Benjamin was also named “Person of the Week” on ABC’s World News Tonight with Peter Jennings, and “Woman of the Year” by CBS This Morning. In 1998, Dr. Benjamin was the United States recipient of the Nelson Mandela Award for Health and Human Rights. She received the 2000 National Caring Award which was inspired by Mother Teresa and was recognized with the Papal honor Pro Ecclesia et Pontifice from Pope Benedict XVI. In 2008, she was honored with a MacArthur Genius Award Fellowship. In 2011, Dr. Benjamin became the recipient of the Chairman’s Award during the worldwide broadcast of the 42nd NAACP Image Awards.

The University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Medicine, the institution from which Dr. Benjamin was conferred her medical degree, compose an article about the former Surgeon General in its UAB Medicine Magazine. The University of Washington’s Steve Scher conversed with Dr. Benjamin in April 2015. The podcast featuring their discussion can be found here.