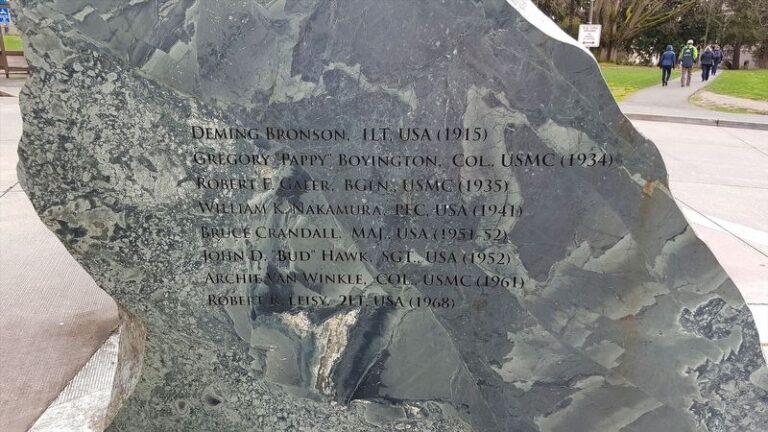

Learn about each of the service members listed on the memorial:

Memorial Location:

Memorial Details:

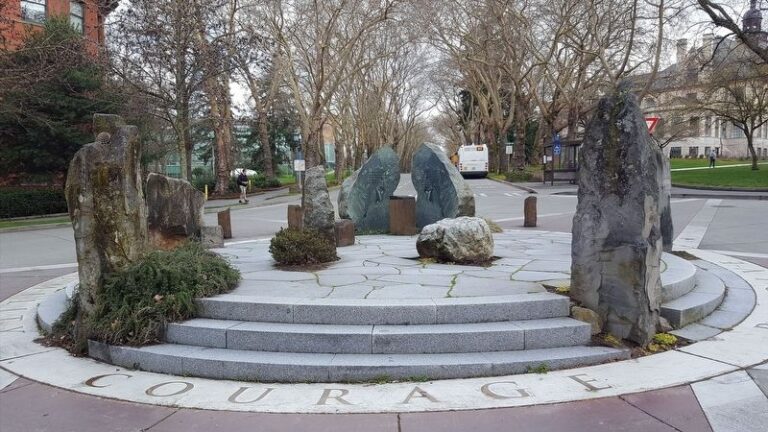

“The memorial is anchored by a five-point star, similar to the medal star. At the north point of the circle is a “book stone.” A plain serpentine rock that sat for years outside the UW sculpture studio was split open like a book and polished. “The stone glows like ordinary people courageous enough to do something extraordinary for their fellow human beings,” said sculptor Heidi Wastweet, who was involved in the project. A basalt column in front of the stone features the face of Minerva, goddess of both wisdom and war, who is pictured on the medal. Near those rocks are four sentinel stones surrounding one with bronze wording from the recipients’ Medal citations.” (text from http://www.washington.edu/visit/valor/)

The Medal of Honor is the “highest military honor given by congress to an individual who demonstrates bravery and personal actions of valor beyond the call of duty” (Congressional Medal of Honor Society). The University of Washington has the most alumni Medal of Honor Recipients from a public institution, excluding the service academies. The Medal of Honor Memorial on UW campus was created to commemorate the outstanding eight individuals for their bravery and actions. The eight individuals from UW who received the Medal of Honor are: Gregory “Pappy” Boyington, Deming Bronson, Bruce Crandall, Robert E. Galer, John D. “Bud” Hawk, Robert Leisy, William Kenzo Nakamura, and Archie Van Winkle.

Michael Magrath, a UW visiting scholar in Sculpture and Public Art, led the team that designed the monument. It included Heidi Wastweet, an acclaimed medallic sculptor, and Dodi Fredericks, landscape architect. Students helped to lead the effort to build the memorial back in 2006, but the motion was initially tabled due to the wave of angry emails ASUW received. This was because originally the memorial was only to honor Gregory “Pappy” Boyington and was deemed not inclusive of the seven other medal of honorees from UW.

In April, the student senate passed a resolution in support of creating a memorial that would include all medal of honor recipients from UW. Leaders of the student senate began launching a $100,000 fund drive in March of 2007 to make the memorial happen. ASUW was successful in raising funds for the monument and money was also raised through private contributions to help pay for the $152,000 project.

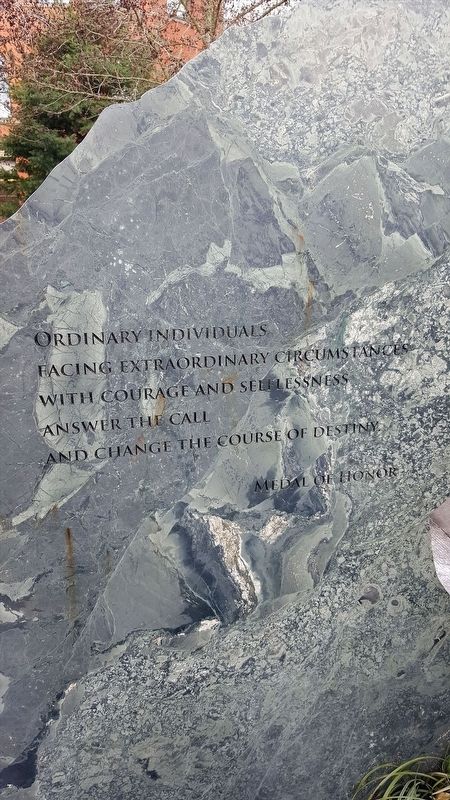

Heidi Wastweet wanted to “inspire students” and for them to think “if these alumni could do extraordinary feats, then they can too”. The construction for the memorial began in August of 2009, was completed by the beginning of the autumn academic quarter, and was dedicated on Veterans day of that year (Honoring Heroes). Their design is anchored by a five-point star, similar to the star on the medal, inset into the traffic circle. At the north point of the circle is the “book stone.” It’s a plain serpentine rock buried for millennia but unearthed at the same time the memorial was conceived. It’s a plain, ordinary looking stone from without, but incredibly tough. Cracked open, it reveals an almost impossible passage, and the inside of a book that records the incalculable forces and complex structure of those men whose names are inscribed upon it.

“A permanent, powerful reminder of the extraordinary things that can happen when ordinary people take action.” This was what UW President Mark Emmert desired for the Medal of Honor monument to do in the minds of people who see the memorial (O’Donnell). And the memorial is standing in UW campus today, doing just that.

References

“Medal of Honor memorial to be constructed near WWI and WWII memorials” Catherine O’Donnell, August 20, 2009, http://www.washington.edu/news/2009/08/20/medal-of-honor-memorial-to-be-constructed-near-ww-i-and-ww-ii-memorials/

“Students Lead effort to Build UW Medal of Honor Memorial” UW Alumni Association,

March 2007, http://www.washington.edu/alumni/columns/march07/content/view/60/38/

“Honoring Heroes – Eight Alumni to be Recognized at Nov. 11 Medal of Honor Memorial

Ceremony” UW Alumni Association, September 2009, http://www.washington.edu/alumni/columns/sept09/hub-heroes.html

“The Medal of Honor” Congressional Medal of Honor Society, 2017, http://www.cmohs.org

“Magrath Sculpture” Michael Magrath, 2017, http://magrathsculpture.com

“Wastweet Studio” Heidi Wastweet, 2016, http://www.wastweetstudio.com/#ArtistStatement