Gardeners are quick to discover that the Seattle area, and most of the coastal areas of the Pacific Northwest, tend to be dry in the summer and wet in the winter, despite our collective rainy reputation. Many popular gardening books are from regions with reliable summer rains. The plant palette these books suggest don’t work here without lots of supplemental water.

Gardeners are quick to discover that the Seattle area, and most of the coastal areas of the Pacific Northwest, tend to be dry in the summer and wet in the winter, despite our collective rainy reputation. Many popular gardening books are from regions with reliable summer rains. The plant palette these books suggest don’t work here without lots of supplemental water.

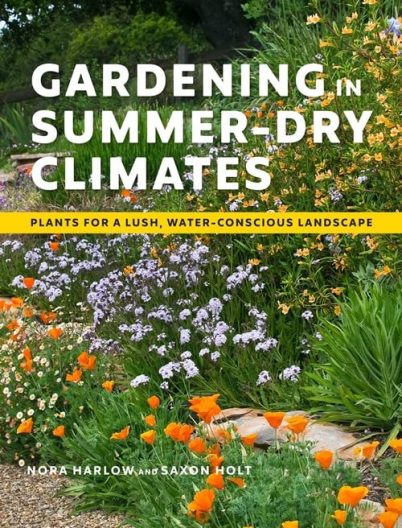

For decades, the encyclopedic “Sunset Western Garden” books have provided local guidance, especially with their fine-tuned zones that not only consider the impact of winter cold, but also summer heat, rainfall patterns, and topography. While the last of these “Sunset” encyclopedias was published in 2012, these zones are now applied in a new book, “Gardening in Summer-Dry Climates” by Nora Harlow and Saxon Holt. The authors also provide the “California’s Water Use Classification of Landscape Species” (WUCOLS) ratings, a handy tool that is useful even in Washington for estimating the water needs of a specific plant.

Both authors are from northern California, but they have done their research on the needs of gardeners further north, making this book useful well into southwestern British Columbia. They recognize that “gardeners up and down the Pacific coast also share an upbeat conviction that the way we garden can make a difference.” This can be achieved in different ways, but a primary tenant is “to work with rather than fight the summer-dry climate.”

The heart of this book is an alphabetical listing of plants chosen not only from the authors’ knowledge, but also the recommendations of an impressive list of regional experts. To me, it feels a bit biased to northern California selections, but this is how the Sunset zones are handy. Knowing that around Seattle you are either in Sunset zone 5 (near the water) or 4 (nearer the foothills), you can make sure the plant will grow for you. The plant selection includes a mixture of trees, shrubs, perennials, annuals, and ferns, many of them natives to the region.

The rich photographs by Holt make this book an especially enjoyable but these images are also well-crafted to give a clear sense of growth habits. Introductory essays and appendices further help with selection of plants, and how to address the special design considerations such as climate trends and the increasing dangers of wildfires. If you’re designing a new garden, or revamping an old, this is an excellent resource to consult.

Excerpted from the Spring 2022 issue of the Arboretum Bulletin