Photo Archive This is a sample of historical photographs. Links below lead to the MEBA homepage and finding aids for papers held at the University of Washington Special Collections Library.

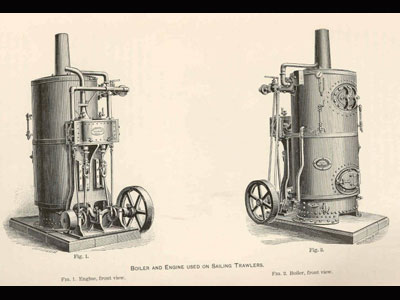

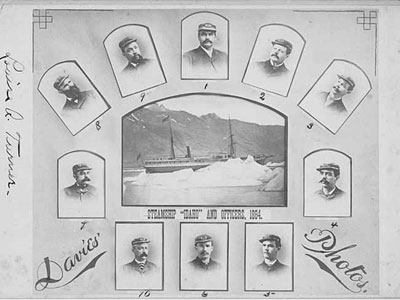

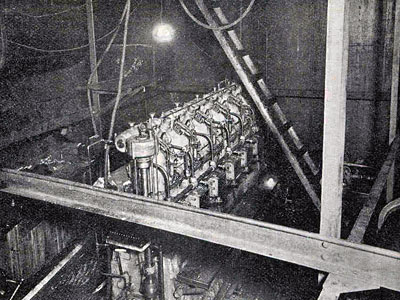

As one of the oldest maritime unions in the United States, the Marine Engineers Beneficial Association (MEBA) has an important place in the history of water-going workers. Founded in 1875 on the inland waterways and Great Lakes of the Midwest, the MEBA formed to protect engineers, boiler, and engine room workers onboard ships. And "protect" is the right word; engine room work was extremely dangerous. In the era of steamships, boilers would frequently explode, killing and injuring nearby workers. Safe working conditions were one of the main concerns of the new union.

The MEBA was created in February of 1875, from city associations formed throughout the Midwest. Since that time it has continued to protect the interests of marine engineers, despite a changing industry and political environment hostile to unionization.

More Information

The Marine Engineers Beneficial Association Here you will find links to the marine engineers homepage, with a history of the union, as well as links to political campaigns, membership information and the union's ongoing work.

The Marine Engineers Beneficial Association Here you will find links to the marine engineers homepage, with a history of the union, as well as links to political campaigns, membership information and the union's ongoing work.  Finding Aid for the papers of the Seattle Local of the National Marine Engineers Beneficial Association, held in the University of Washington Special Collections.

Finding Aid for the papers of the Seattle Local of the National Marine Engineers Beneficial Association, held in the University of Washington Special Collections. The history of the engineers largely follows that of the rest of the maritime industry. The engineers won legislative and organizational victories with the rising tide of the labor movement in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. However the union, like many other maritime trades, was effectively crippled after the disastrous 1921 sailors' strike. Because of their crucial position on the vessels, the engineers were considered the backbone of the strike; when President Harding intervened to support shipping companies, the engineers went back to work, and the strike collapsed with the sailors of the ISU holding out the longest. The strike ended with a reduction in wages, and the unions that survived barely hanging on.

By 1934 the MEBA was so weakened it did not hold an annual convention. However, in that same year the tide was changing for the labor movement. The ’34 maritime strike was one of the most dramatic and consequential in US history. Conflicts between strikers and police on the Embarcadero and Rincon Hill in San Francisco resembled pitched military battles; five longshoremen were shot and killed by police in San Francisco and two in Seattle. The engineers in San Francisco engaged in sympathy strikes with the striking longshore workers, and the longshore victory 3 months later was a boon to maritime workers, and the labor movement on the West Coast in general. By January of 1935 the San Francisco local had more than doubled its membership, and by 1939 the union had nearly half of the nation's salt-water tonnage under contract; the '34 strike was a turning point for a decade long revival.

In the post-war the period the engineers participated in the largest strike wave in US history as part of the Committee for Maritime Unity. A 1946 strike was a bitter fight for better conditions and strengthening the union, which in many ways was largely successful, but at the cost of losing a union hiring hall for the next several years. It wasn't until the early '50s that the MEBA was able to win a modified hiring hall from employers. But like so many periods in maritime history, the high water mark of union strength in the mid 1950s began a long period of decline.

In the later part of the twentieth century the MEBA, like much of the labor movement, has struggled to maintain itself in a changing industry. Automation and a reduction in US based shipping has led to a dramatic reduction in membership. Following WWII the US merchant marine fleet shrunk from 43,000 to fewer than 2,000 vessels; by the end of the century less than 3 percent of national cargo was carried in American ships. Despite the obstacles the MEBA continues to represent the interests of engineers and engine workers. On their website you will find links to the union's history, as well as updates on their current struggles.