The International Fisherman and Allied Worker, January 1947

The monthly newspaper was the voice of IFAWA from 1944 until its demise in 1951.

This prize winning essay is presented in five chapters.

Chapter 1: Introduction

Chapter 2: Early Unionism in the Pacific Coast Fisheries

Chapter 3: A Coastwise, Industrial Union

Chapter 4: World War II

Chapter 5: Struggle, Strikes and Collapse

Leo Baunach's essay won the 2013 Library Research Award given by University of Washington Libraries.

Fishing story on Labor Radio 1950

Reports from Labor was a fifteen-minute, biweekly labor radio show that aired in Seattle hosted by Jerry Tyler, a member of the Marine Cooks and Stewards Union. In the photo above Tyler (center) sings with Trudy Kirkwood and Paul Robeson . See Leo Baunach's article, Seattle's CIO Radio: Reports from Labor.

For the August 1, 1950 show Tyler described a night spent gill netting for salmon on the Columbia River with Phil Lasich of the Columbia River Fisherman's Protective Union, an IFAWA affiliate. Listen to the 10 minute broadcast below. Here is the transcript.

(courtesy Ronald Magden):

by Leo Baunach

In late July 1950, labor organizer and radio host Jerry Tyler accompanied Phil Lasich on his nighttime shift fishing for salmon on the Columbia River. Lasich had worked in the industry since the age of 16 and rented a boat from the Columbia River Packers Association (CRPA), a salmon canning corporation. As part of the rental agreement, he sold his catch exclusively to the company. The two left the docks at 6:45 pm, taking advantage of reduced visibility for salmon during nighttime. Lasich had spent the day painstakingly preparing 1,200 feet of net, which he owned and was worth roughly a dollar per foot. Once on the River, they quickly deployed it and remained in place all night. At dawn, Lasich hauled in his catch and returned to shore.

That night he netted three salmon weighing a total of 85 pounds and received around seventeen dollars from the CRPA for the catch - a pittance considering the hours of preparation, the long night on the river, the investment in the net, and the boat rental. Thanks to his membership in the Columbia River Fishermen’s Protective Union, an affiliate of the International Fishermen and Allied Workers of America, Lasich was at least guaranteed a pre-negotiated price per pound. Concluding that Lasich’s yearly earnings were about the same as an unskilled wage laborer, Tyler asked him why he stayed in the tiring and dangerous work of fishing. The fisherman “squared his shoulders and threw his head back and grinned a grin that spoke volumes,” responding “I got in it because I grew up in it. I stay in, well…no boss, no time clock.”[1]

His succinct answer reveals much about the lives and attitudes of West Coast fishery workers during the era. They greatly valued their independence, which gave them control over the rhythms of their work and kept out the rigid discipline of the factory floor. Nevertheless, West Coast fishermen had long understood themselves as workers for corporations like the Columbia River Packers Association, and used collective action to gain a share of the profits derived from their labor. Like many fishermen, Lasich came from a close-knit immigrant community that was deeply tied to the industry. Five of his family members worked as fishermen, and the older members had fished in Eastern Europe before they came to Oregon.

This essay explores how Lasich and his compatriots came to be part of a militant working-class movement of fishermen and cannery workers that stretched from San Diego to the Bering Sea, and joined up with the Congress of Industrial Organizations to fight for better conditions in one of the most iconic industries on the West Coast.

Little has been written about the International Fishermen and Allied Workers (IFAWA). An article by geographer Geoff Mann is the only scholarly account of the union. The CIO published a book about IFAWA in 1947, during the union's growth phase.[2] This essay builds upon Mann’s essay to create a fuller chronology of the union’s history, and address questions like ethnicity and gender that he suggested for further study. My information is mostly drawn from the “International Longshoremen's and Warehousemen's Union Fishermen and Allied Workers Division, Local 3 Records,” housed in the Labor Archives at the University of Washington. The rarely used collection contains the surviving documents from Joseph Jurich, President of IFAWA from formation to dissolution and longtime staffer of an ILWU fishermen’s local in Seattle afterwards. This includes local minutes, International records and meeting notes, annual conventions, and correspondence. The paper also draws on the union’s newspaper published from 1944 to 1951, and other published sources Because the sources for this essay were mostly produced by the union, and its leadership in particular, there are limits to the interpretations presented. Facts have been checked whenever possible, and I have tried to read between the lines of the materials produced by paid officers and staff.

This essay adds a new dimension to historical understandings of the fate of left-wing unions and Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). IFAWA was one of the eleven unions expelled from the CIO for connections with the Communist Party, yet is largely absent from literature on the CIO. When mentioned at all, the references are brief and erroneous.[3] As we will become apparent,IFAWA was an important part of the CIO on the West Coast, helping to make the waterfront a crucial space of labor action and radicalism. The union was also active in the national CIO and co-authored the infamous 1949 minority report that staunchly opposed the leadership of the federation. Contained within the story of IFAWA is the broader history of the CIO; from the successful organization of new sectors through industrial unionism, to the support of the war effort and the cannibalistic expulsion of eleven unions. IFAWA never exceed 30,000 members, but it achieved a critical mass of union density in a strategic and primary industry of the Pacific Northwest and Alaska.

Further, IFAWA is a case study in CIO civil rights unionism and multiracial labor unity.[4] This essay describes the struggles of Bristol Bay Alaska Native cannery workers and their alliance with Asian-American workers from the Pacific Northwest. In doing so, another dimension is added to the emerging scholarship on Filipino cannery workers and civil rights unionism more broadly.[5] Similarly, this paper reveals the crucial role played by Yugoslavian immigrants in the formation and politics of the union, adding to analyses that foreground immigrants in the history of the CIO.[6] Outside of labor history, this paper adds a new perspective to the sparse set of literature on commercial fishing and canning in Puget Sound and Alaska, which is dominated by company histories, studies of regulatory regimes and historical studies that focus either on the inception of the industry in the industry in the late 1800s or its decline after the 1950s.[7]

Industrial geography of fishing

The Croatian enclave of South Bellingham housed the world’s largest cannery and was just one of many immigrant communities that revolved around the commercial fishing industry. During spring in South Bellingham, the smell of tar wafted up from the docks as fishermen dipped their cotton nets in a pungent mixture that reinforced the gear for use in saltwater. After months of preparation, the entire community would turn to see a portion of the fleet leave for Alaska for the summer fishing season.[8] In 1939, the Pacific Coast industry employed roughly 34,642 fishermen and 33,913 workers in marine transportation, processing and canning.[9] When mass production of canned salmon first began on the Columbia River second half of the 19th century, Norwegian, Finnish and other Scandinavian immigrants with maritime traditions did the extremely dangerous work of fishing. Workers from these same immigrant groups worked alongside Asian-Americans in the grueling cannery assembly lines, albeit often in segregation. In the ensuing decades, Yugoslavian immigrants became increasingly important in the fishing section of the industry and Filipinos became the main form of Asian-American labor after Chinese exclusion. In Southern California,. Italian predominated and significant numbers of Japanese immigrants established themselves as fishermen.[10]

Fishery Resources of the United States (Government Printing Office, 1945)

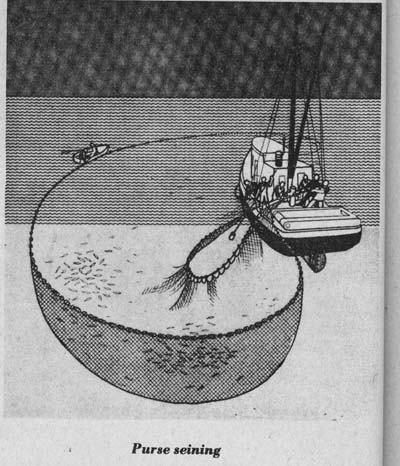

The Croatian fishermen of Puget Sound usually worked on purse seiners, boats designed to use purse seine nets. Each boat had a crew of nine to eleven. While on the fishing grounds, a lookout watched for signs that a school of fish was nearby. When fish were spotted, a small skiff was deployed. Vessel owners began to add outboard motors to the skiffs in the 1940s, but the usual form of propulsion was rowing. The larger boat towed the net - which was up to 2,000 feet in length and 40 feet tall - away from the skiff to form a wall. To keep the net fanned out in the water, small pieces of cork were attached to the top of the net and small lead weights to the bottom. Once fish gathered behind the net, the skiff moved in a circle and met up with the boat. The ‘purse’ in the name came about because the ropes attached to the bottom of the net would be tightened, like closing a purse with a drawstring. Now, the fish were trapped and the crew pulled the net back into the boat. As with the skiffs, motorized tools appeared in the 1940s to haul the net but physical labor remained the main method until the 1950s.[11]

In addition to purse seines, the main types of nets were gillnets, trawls and reefnets. Gillnetting was briefly explained in the introduction. Boats were generally smaller than purse seiners and required one to four people as crew. Fish attempted to swim through the net and were trapped by their gills. The other main form of net fishing on the West Coast was trawling. A trawl net is attached to long ropes and dragged near the seafloor. The most common form in the 1930s and 1940s was otter trawling, named as such because of ‘otter boards,’ two pieces of wood on opposite sides of the net that kept it open. Trawl nets tapered to a closed end. The method grew quickly in the early 1940s and mostly caught flounders. Reefnetting was unique to the Puget Sound and concentrated near Lummi Island. Two boats positioned themselves above shallow underwater reefs and stretched a net between them to intercept a fish run.[12]

The nature of fishing on Puget Sound was altered in 1934 when fixed trap fishing was banned and more sites, like those used by reefnetters, became available.[13] Traps varied in size, but the most important ones were large ones owned by cannery companies. Located near rivers and bays where fish migrated, these traps consisted of a long, fence like structure that extended outward, sometimes several hundred feet. The fence blocked the movement of the fish, who would swim through a series of increasingly small enclosures until becoming trapped in a small pot. These structures required relatively little labor input, just a few watchmen to prevent stealing and a few workers to collect the fish, but a very high capital investment was needed for construction and could only be mustered by large canning corporations. This greatly angered fishermen, who felt that traps undermined their earning power and unfairly intercepted their catch. [14] Traps continued to be allowed in Alaska until statehood in the late 1950s. In Alaska, white and Native residents staffed traps, while in Puget Sound it was mostly a Norwegian endeavor. The Washington ban precipitated a shift toward greater numbers of Yugoslavian fishermen, but Norwegians continued to operate in the industry as troll fishing grew in popularity.

Trolling was the predominate form of fishing with lines. Troll boats had sturdy poles, usually six in total, which extended from the deck. Each pole had a line attached to it with baited hooks, and a pulley to reel in the line. Trollers slowly dragged the lines behind them and could be manned by one or two people. Halibut were caught further offshore using long lines that lay on the seabed, held in place by anchors and floats. Almost the entire halibut fleet was based out of Seattle, and remained strongly Norwegian. The most unique method of fishing in this era was used for tuna. When a school was spotted, some of the crew would begin to throw bait into the water to keep the school in the same area. Meanwhile, the rest of the crew used bamboo fishing pools with short lines and live bait to bring the tuna aboard by hand. Tuna could also be purse seined and were mainly caught off California, along with a smaller Northwest fishery.[15]

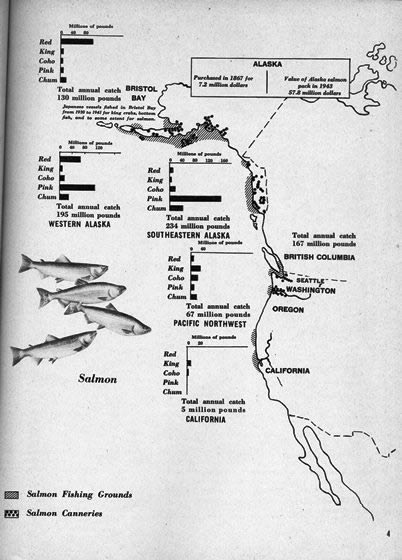

Principal salmon fisheries,

Fishery Resources of the United States (Government Printing Office, 1945)

With proper adjustment, different gears could be used to catch multiple types of fish. For example, purse seining was normally used to catch salmon in Washington and Alaska, but in California was used to fish for sardines. Salmon was the most important of the West Coast catches. Alaska produced 54% of the world’s canned salmon in 1939, or some 251 million pounds after processing, with the rest of the Coast contributing another 4%.[16] The catch fluctuated greatly – the previous year Alaska produced over 235 million pounds and the West Coast outside Alaska represented 7% of world production – but these numbers are illustrative of the scope of the industry. The West Coast accounted for roughly half of the fish caught in the United States in any given year in the 1940s. Moreover, high-value, high-quality products like salmon and halibut set it apart and ensured that fishing remained an integral part of the regional economy. The pilchard, or Pacific sardine, was also an important catch, though it was of lower uality than salmon or halibut. Much of it was canned, and like sardines were used for fish oil or as bait for other fishing operations. The catch in California exceeded the rest of the Pacific Coast in size, but unlike Alaska and the Northwest was based on lower-quality fish like sardines and mackarel. Tuna, herring and flounder were the other important catches of the Pacific Coast in terms of value and quantity. Unique to the 1930s and 1940s was an explosion of shark fishing. It was discovered that sharks concentrated vitamin A in their livers, providing a substitute for cod liver oil that became extremely valuable when World War II cut imports from Scandinavia.[17]

The varying life cycles and habitats of these catches meant that many fishermen worked far from their homes. Of the 25,000 people who worked in the Alaska fishing industry, 75% lived the rest of the year in Washington.[18] These fishermen and cannery workers were accordingly termed ‘non-residents.’ There was recurring tension with the Alaska Native and white ‘residents’ that made up the rest of the workforce. Alaska was not yet a state and remained a territory of the federal government. It is most accurate to say that Alaska was a colony administered from Seattle. The Jones Act of 1920 mandated that all shipping to the Territory be handled by American companies, which in practice meant that all vessels had to pass through Washington State.[19] Fishing was the driving economic force of Alaska and generated 70% of its meager tax revenues, with the rest being repatriated stateside by absentee canning corporation and non-resident workers.[20] I will return to this shortly, but first it is important to map the major fishing sites of the Pacific Coast.

Commercial canning in the West Coast began on the Columbia River, which in the 1940s continued to be an important salmon site plied by gillnetters and a growing number of trollers. The vast territory of Alaska was more often understood as four distinct districts than as a single unit. The first was Bristol Bay, a large inlet on the Bering Sea connected to several salmon spawning rivers around Dillingham. Here, a peculiar situation arose in which only gillnet sailboats were allowed until 1951, even though fishermen on the rest of the Pacific Coast relied on motors. The canning companies consistently lobbied for regulatory rules banning motors in the name of conservation, but most observers concluded that the companies, in contrast to their behavior elsewhere, wanted to keep control of the workforce and feared motorized boats would lead to restive owner-operators.[21]

Bristol Bay was the main site of production for sockeye salmon, the best of the species for food consumption. To the Southwest of Bristol Bay was the ‘Westward’ area, comprising the Aleutian Islands and the Alaskan Peninsula, including Kodiak. To the East was the Central district, centered on Cordova, where motorized gillnets fished near the Copper River. Finally, there was the Southeast District that comprised the Alaska panhandle running alongside the Canadian Yukon near Ketchikan. Alaska was overwhelmingly focused on salmon. The values of the Alaskan salmon catch exceeded the next biggest catch, halibut, by a factor of almost thirty. Herring was the third most important, and was worth only half the total value of halibut. Like pilchard, it was used for food consumption as well as reduction into oil and non-food products.[22] The catch of salmon in Washington and Oregob paled in comparison to Alaska, but the two states were an important source of chinook salmon, the largest of the species and well suited to canning and food consumption.[23]

Fishermen and Cannery Workers

The rhythms of fishing varied greatly. Gillnetters on the Columbia returned to port every night, while Bristol Bay gillnetters found sheltered inlets and slept on-board. Regulations generally allowed for fishing from early Monday to late Friday or Saturday. On Puget Sound purse seiners, crews slept on board for a few hours a night before working shifts of more than fourteen hours. They returned to port on the weekend to mend nets and rest. To allow the boats to stay on the most advantageous fishing grounds and not waste precious time by sailing to a cannery, companies directly owned tender boats. These larger vessels allowed the fishing boats to offload their catch, which needed to be processed or canned within twenty-four or forty-eight hours of being caught. If fishermen were near a cannery or were returning for the weekend, they gave their catch to scows which brought it to the cannery gate. In contrast, deep sea fishing like halibut and tuna required voyages of up to three weeks.[24]

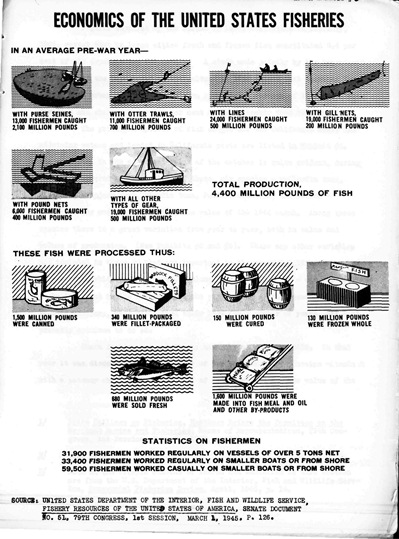

Fishery Resources of the United States (Government Printing Office, 1945)

Industrial fishing in the 1930s and 1940s was oriented toward canning, an easy method to mass manufacture, preserve, transport and sell the product. Especially in Alaska, it was more advantageous to build many small canneries than a few large facilities, in order to maximize proximity to fishing grounds. In 1938, there were 116 cannery facilities in Alaska and an additional 114 plants engaged in reduction, curing, filleting, freezing and other processing activities. In Washington, there were a total of 117 canning and processing facilities.[25] ‘Shoreworkers’ was often used to describe all fish processing workers, not just those in canneries. In salmon canning, the number of facilities mirrored the disparity in catch size and geographic scope, with 83 canneries in Alaska in 1943 and 19 in Washington, Oregon and California.[26]

At canneries, fish were offloaded from tenders or scows onto a conveyer belt or chute. From there, the fish were sorted by type or size and placed one-by-one on a conveyor belt. The ingloriously named Iron Chink, so-called because it replaced the manual work originally performed by Chinese migrant workers, automatically chopped of the head and tail, and cut open the belly. Next, workers called ‘slimers’ washed the fish and made sure the guts were taken out. A large portion of the cannery workforce was women, usually from the same immigrant communities as fishermen, and slimers were usually all female. Moving along the assembly line, machines cut the fish into standard lengths corresponding with the size of a can. Most canneries manufactured their own cans from flat sheet metal. Empty cans were filled with the cut pieces of fish and vacuum sealed. Finally, the sealed cans were placed inside large pressure cookers.[27] The process, the amount of mechanization and shop floor gender divisions varied by time and place. Work in reduction plants could be particularly unpleasant. Fish like herring were pressure cooked, making a pulp that separated into oil and solid material. The solid material was dried over flames and the water removed from the oil by centrifuge. The smell of both processes, and particularly the drying of the solids, was indescribably pungent.[28]

The ethnicity of the workforce varied greatly. Cannery workers in Puget Sound were mostly European immigrant women.[29] On the Columbia River, there were significant numbers of Asian-American and Mexican workers alongside white immigrants. In Alaska, the seasonal nature of the work, the small local population and the scattered, inaccessible isolation of the canneries led companies to contract Asian-American male laborers, a majority of whom were Filipino, and seasonally ship them north from Seattle, Portland and San Francisco.[30] Alaska Natives were mostly shut out of the industry, but served as a reserve pool of labor. This changed dramatically during World War II when travel restrictions restricted the Asian-American workforce. Alaska Natives soon composed up to half the cannery workforce, a proportion that stuck after the war.[31]

The constant pace of the industrial assembly line in a cannery and the more variable rhythm of work on fishing boats differed greatly, but two things tied these workers together: safety hazards and a relationship with a large corporation. In the canneries, machines posed a constant safety problem and repetitive stress injuries were common. Both fishermen and cannery workers had to be careful to avoid fish poisoning caused by bits of guts or other material coming into contact with small cuts. By the 1930s, mortality among fishermen had decreased since the early days of the West Coast commercial fishery, but shipwrecks continued and serious injury always loomed. Problems ranged from acute injuries due to engine fires and falls to chronic problems from fuel vapor inhalation, and the combined stress of long hours, irregular sleep, meager on-board diets and physical labor.[32]

Workers or independent contractors?

By forming a union, fishermen and cannery workers sought to change these conditions. To do so, fishermen first had to assert themselves as workers entitled to collective bargaining. Boat and gear ownership varied by area and catch, but a relatively small number of companies controlled canning, processing and distribution. These companies received profit based on the labor of fishermen, with whom they had a lopsided relationship. After an intitial explosion of Pacific Coast canning companies in the 1870s, there was a trend toward consolidation. The Columbia River Packers Association and the San Francisco-based Alaska Packers Association began as loose combines for the purpose of joint ventures but eventually became single companies.[33] The Alaska Salmon Industry, referenced throughout this paper, was not a single company but an employer’s association that bargained with unions. Other companies expanded to the West Coast, like the New England Fish Co. from Boston or Booth Fisheries from Chicago. Pacific American Fisheries was based in Bellingham but financed and sometimes controlled from Chicago.[34]

There were also medium-sized companies that started on the Puget Sound, like Washington Fish and Oyster Co. or the Fishermen’s Packing Corporation. The latter was formed by vessel owners, and despite their name functioned like any other corporation.[35] Most large and medium companies had operations in Alaska, and formed a stateside clique of absentee capital that profited off the natural resources of the territory. Their relationship with fishermen was not much different. The CIO estimated that American packers and wholesalers made a gross profit of around $50 million in 1945, while fishermen received an average income of $1,000.[36] ‘Packers’ will be used throughout this essay as a blanket term for large fish product corporations, although ‘canners’ and ‘operators’ were also used at the time.[37]

Unionizing as workers to make demands of the packers was complicated by the lack of uniformity in employment relationships in the industry. Purse seiners in Puget Sound were owned by individuals who did not fish and often owned several boats. These vessel owners hired the crew and paid them in pre-set shares of the money received from the packers for their catch. In Bristol Bay, gillnet fishermen were direct employees of packers who furnished them with boats and gear. In the Copper River and Prince William Sound area, non-resident fishermen were compensated for travel expenses and rented boats and gear from the company. In contrast, resident fishermen in nearby Cook Inlet usually owned boats because marine transport was the main form of travel between isolated areas during the off-season. Workers on tending boats were always direct employees of the packers.

Despite this patchwork of relationships, every boat delivered exclusively to a single company. From the beginning of the Pacific Coast commercial fishing, informal and formal agreements of this nature were made before the season began. Packers policed fishermen to ensure that they did not sell their catch to another company, though this was often not necessary because of the long distances between canneries and the need for quick delivery to prevent spoilage. By misclassifying fishermen as non-employees, packers minimized the risk taken on by the company for bad seasons and accidents. However, many packers advanced credit to fishermen to buy or rent boats and gear, thereby creating a relationship of dependency.

Whether the money came from a packing company or the bank, fishermen that owned their own boats could rarely expect to ever get out of debt. Of equal importance was the fact that the earnings received by fishermen, whether owner-operators or crew hired by a vessel owner, were directly tied to the price set by the packers. Before unionization, packers had complete control to set prices and change them without notice, to arbitrarily reject deliveries over quality or to tell fishermen who had promised to fish exclusively for their company that a quota had been met and they should dump their catch and receive no payment. Packers became infamous for price collusion, backdoor deals and mergers that unfairly distorted the market.[38] These conditions in the fishing industry led fishermen to understand themselves as de facto workers for the packers and band together to demand accountability.

Next: Chapter 2- Early Unionism in the Pacific Coast Fisheries

[1] Reports from Labor, August 1, 1950, Jerry Tyler Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. < https://depts.washington.edu/dock/tyler_audio/August_1_1950.pdf>

[2] Geoff Mann, “Class Consciousness and Common Property: The International Fishermen and Allied Workers of America,” International Labor and Working-Class History 61 (2002): 141-160; Geoff Mann, Our Daily Bread: Wages, Workers, and the Political Economy of the American West (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007), 115-141; Geoff Mann, “International Fishermen and Allied Workers,” in Encyclopedia of U.S. Labor and Working-Class History ed. Eric Arnesen (New York: Routledge, 2007), 674-5.

[3] Judith Stepan-Norrisand Maurice Zeitlin, Left Out:Reds and America’s Industrial Unions (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 17. Incorrectly puts IFAWA in a list of unions that stayed in the National CIO when Communist officers were removed before an expulsion trial was held. Harvey Levenstein, Communism, Anti-Communism and the CIO (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1981), 69. Dates the IFAWA-ILWU merger to 1949, not 1950, and makes an overly broad characterization of IFAWA and the Marine Cooks and Stewards as ‘minor outposts of Bridges’ empire.’Steven Rosswurm, ed., The CIO’s Left-Led Unions (New Brunswick, N.J. : Rutgers University Press, 1992), 3. mentions IFAWA only once and pegs it membership at less than half its size around the time of expulsions. This number may have slightly over-accounted for the split with the Alaska Fishermen’s Union.

[4] Robert Korstad and Nelson Lichtenstein, “Opportunities Found and Lost: Labor, Radicals, and the Early Civil Rights Movement,” The Journal of American History 75, no. 3 (1988): 786-811

[5] Chris Friday, Organizing Asian American labor: the Pacific Coast canned-salmon industry, 1870-1942 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1994).:Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project, “Filipino Cannery Unionism Across Three Generations 1930s-1980s.” <http://depts.washington.edu/civilr/Cannery_intro.htm>

[6] Thomas Göbel, “Becoming American: Ethnic workers and the rise of the CIO,” Labor History, 29, no. 2 (1988): 173-198

[7] David Arnold, The Fishermen’s Frontier: People and Salmon in Southeast Alaska (Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 1986), 139-155. An excellent overview of labor history in Alaska salmon canning, but one that oddly fails to name IFAWA but describes it indirectly through references to the CIO. Mistakenly identifies Joe Jurich as representing the Alaska Fishermen’s Union, and I would argue that the Alaska Salmon Purse Seiners Union was not organized independently but was a split from the Puget Sound-based Salmon Purse Seiners Union (see: Alaska Purse Seiner’s Union Convention September 11, 1937. box 11). Nevertheless, a succinct and sharp analysis. August Radke, Pacific American Fisheries, Inc.: History of a Washington State Salmon Packing Company, 1890-1966 (Jefferson, N.C. : McFarland & Co., 2002), 151. Contains a discussion of labor including the Alaska Fishermen’s Union and the Cannery Workers and Farm Laborers Union. Irene Martin and Roger Tetlow, Flight of the Bumble Bee: The Columbia River Packers Association & A Century in the Pursuit of Fish (Long Beach, WA: The Chinook Observer, 2011). Contains some discussion of the Columbia River Fishermen’s Protective Union, International Seamen’s Union and Pacific Coast Fishermen’s Union.Karen E. Hébert, “Wild Dreams: Refashioning Production in Bristol Bay, Alaska” (PhD diss., University of Michigan, 2008). Picks up the labor history of the area in 1951, just after IFAWA’s demise.Richard Cooley, Politics and Conservation: The Decemberline of the Alaska Salmon Industry (New York, Harper & Row, 1963). Contains the most extensive discussion of labor in the Alaskan salmon industry. Patricia Roppel, Salmon from Kodiak: A History of the Salmon Fishery of Kodiak Island, Alaska (Anchorage: Alaska Historical Commission, 1986).Arthur McEvoy, The Fisherman's Problem: Ecology and Law in the California fisheries, 1850-1980 (Cambridge University Press, 1986), 173-4.

[8] Steve Kink, “Bellingham's Croatian Community and Commercial Fishing: A Reminiscence by Steve Kink,” Historylink: the Free Online Encyclopedia of Washington State History. <http://www.historylink.org/index.cfm?DisplayPage=output.cfm&File_Id=8384>Radke, Pacific American Fisheries.

[9]R.H. Fielding, Fishery Industries of the United States 1939 (Washington, D.C.: United States Department of the Interior, Bureau of Fisheries, 1941) 475-491; 542

[10]Sverre Arestad, “Norwegians in the Pacific Coast Fisheries,” Norwegian-American Studies 30: 96-129. < http://www.naha.stolaf.edu/pubs/nas/volume30/vol30_04.htm>; Connie Chiang, Shaping the Shoreline (Seattle : University of Washington Press, 2008).This paper uses the term ‘Yugoslavian’ because it was often used in union record as a self-identifying term. The terminology used to describe migrants from the Balkans in the 19th and 20th century was slipshod and often erroneous. They were sometimes called ‘Austrians’ because of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, or Slavs or Slovenians. The majority of Yugoslavians in the West Coast fishing industry were from the coast and islands of Croatia.

[11] Carl Wick, Ocean Harvest: The Story of Commercial Fishing in Pacific Coast Waters ( Seattle, Wash., Superior Pub. Co., 1946), 63-68. Bret Lunsford, Croatian Fishing Families of Anacortes (Anacortes, Wash.: American Croatian Club of Anacortes, 2011), 95-136. Felix Montes Alaska Fishermen and the Anti-Trust Laws (master’s thesis, University of Washington, 1947), 44.

[12] “Working Agreement of the Puget Sound Reefnetters Local Union No. 4 booklet,” Lummi Island Community Club Archives. <http://content.statelib.wa.gov/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lummi/id/43/show/38/rec/1>

[13] Arestad, “Norwegians in the Pacific Coast Fisheries.”

[14] Montes Alaska Fishermen 52-56

[15] Wick, Ocean Harvest.

[16] Washington State Bureau of Statistics and Immigration, Washington, Its People, Products and Resources (Washington: Secretary of State, 1940), 90. Fiedler, Fishery Industries of the United States 1939,540-6.A case of canned salmon meant 48 one-pound cans. See: Montes, Alaska Fishermen, 27

[17] Secretary of the Interior. Fishery Resources of the United States (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1945), 3-41. An excellent overview of the Pacific Coast fishing industry that synthesizes much of the same sources used here is: “Report of the Federal Trade Commission on Distribution Methods and Costs, Part IX: Costs of Production and Distribution of Fish on the Pacific Coast,” (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1946).

[18] Washington, Its People, Products and Resources, 89

[19] Chris Friday, “Competing communities at work : Asian Americans, European Americans, and native Alaskans in the Pacific Northwest, 1938-1947,” in Over the Edge: Remapping the American West, ed. Valerie Matsumoto and Blake Allmendinger (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), Page 308. Eric Gislason, “A Brief History of Alaska Statehood (1867-1959).” <http://xroads.virginia.edu/~cap/bartlett/49state.html> . As a territory, Alaska was not afforded protections surrounding inter-state commerce clauses.

[20]Cooley, Politics and Conservation, 182. Secretary of the Interiror, Fishery Resources, page 3

[21] Tim Troll, Sailing for Salmon: The Early Years of Commercial Fishing in Alaska's Bristol Bay, 1884-1951 (Dillingham, AK : Nushagak-Mulchatna/Wood Tikchik Land Trust, 2011), 39.

[22] Fielding, Fishery Statistics of the United States, 194-9. Secretary of the Interior, Fishery Resources of the United States, 9-10

[23] Ibid., 4

[24] Ibid., 21

[25] Fielding, Fishery Statistics of the United States, 544; 480

[26] A.W. Anderson, E. A. Power and the Department of the Interior, Fishery Statistics of the United States 1943 (Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1947), 23

[27] Wick, Ocean Harvest 60-63. Louise Otten,“Reporter Visits Salmon Cannery in Anacortes,” International Fisherman and Allied Worker, September 1945, 10. Hereafter, the International Fisherman and Allied Worker will be abbreviated as ‘IFAW.’

[28]City of Richmond, “Herring Reduction,” In Their Words: The Story of BC Packers, <http://www.intheirwords.ca/english/canning_herring.html>. Also contains an excellent overview of the salmon canning process and the different gears.

[29] Kathleen Young, “The Diversity of Croat-Dalmatian Ethnic Identity in Northern Puget Sound” (PhD. Diss., Simon Fraser University, 1994), 204.

[30] Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project, “Filipino Cannery Unionim.”

[31] Friday, “Competing Communities at Work,” 314. James VanStone, Eskimos of the Nushagak River: An Ethnographic History (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1967), 80.

[32] ‘4th Convention IFAWA, December 1-4, 1942, Seattle,’ box 12, folder 2, Page 56, International Longshoremen's and Warehousemen's Union Fishermen and Allied Workers Division, Local 3 Records

1935-1981, University of Washington Special Collections, accession number 3466-001. Paul Pinksy, Sanford Goldner and Philip Eden, “Fisheries of California: The Industry, the Men, their Union (San Francisco, CA: California CIO Council, 1947), 37.

[33] Western Washington University, “Guide to the Alaska Packers Association Records 1841-1989” <http://nwda.orbiscascade.org/ark:/80444/xv77299>

[34] University of Washington Special Collections, “Guide to the New England Fish Company Records

1902-1983,” <http://digital.lib.washington.edu/findingaids/view?docId=NewEnglandFishCompany3996.xml>. Martin and Tetlow, Flight of the Bumble Bee

[35]Ed Dinger, “Ocean Beauty Seafoods, Inc.,” in International Directory of Company Histories 68, ed. Tina Martin (Detroit, Mich.: St. James Press, 2005).

[36] Pinsky, Fisheries of California, 54

[37] Dealers was another term, indicating a company that sold fresh fish. Large packing companies often had a smaller division engaged in fresh fish dealing, and there were many medium and small businesses-especially in Southern California – that were exclusively dealers.

[38] Pinsky, Fisheries of California 170-180; 52-8. Courtland Smith, Salmon Fisheries of the Columbia (Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 1979), 57-58. Montes, Alaska Fishermen, 1-26. Radke, Pacific American Fisheries, Inc., 136; 163