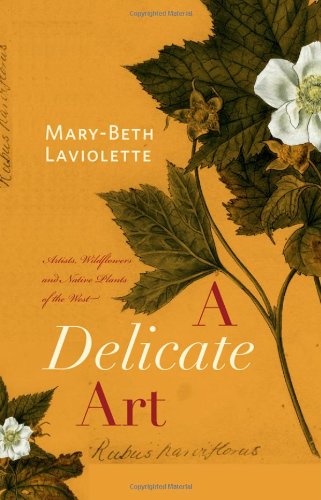

In the late 19th century in western Canada there were two women who, while not sisters, had a lot in common. Much of their stories are found in “A Delicate Art: Artists, Wildflowers and Native Plants of the West” by Mary-Beth Laviolette.

In the late 19th century in western Canada there were two women who, while not sisters, had a lot in common. Much of their stories are found in “A Delicate Art: Artists, Wildflowers and Native Plants of the West” by Mary-Beth Laviolette.

Mary Schäffer Warren (1861-1939) and Mary Vaux Walcott (1860-1940) were both of Quaker families living in Philadelphia, arguably the center for science and culture in America at the time. They both developed strong interests in the natural world, and developed the skills to paint in watercolors the native plants they found.

They joined a trip of the Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences to the Rockies and Selkirk Mountains of eastern British Columbia and western Alberta in 1889, traveling together part of the way on the top of a box car! They brought this same adventuresome passion to hiking and exploring the peaks, returning every summer for many years.

The pathways of the two Marys eventually diverged. Warren married her first husband, Charles Schäffer, who she met in during one of these summer trips. He was an avid amateur botanist and together they continued their study of the local flora with the intent of publishing a field guide, using his text and her illustrations, both color paintings and black-and-white photographs.

Sadly, Charles Schäffer died before the book was completed, but his friend and fellow member of the Academy, botanist Stewardson Brown, completed the text. “Alpine Flora of the Canadian Rocky Mountains” was published in 1907. It profiles 163 plant species including trees, shrubs, and ferns, but the focus is on herbaceous wild flowers. The illustrations are lovely, but the book suffered by comparison to other popular field guides of the time by not quite satisfying either a professional or a general audience. The text is brief in its description of the flowers and foliage, and lacks the lyrical treatment of the guide published one year earlier by Julia Henshaw.

After that accomplishment, Warren became more of an explorer. Quoting author Laviolette, this “meant getting used to riding a horse, camping in all kinds of weather and travelling in the company of men who were neither family nor spouse.” She eventually moved to Banff, Alberta, married her second husband, guide Billy Warren, and is best known today for her mapping and discoveries in what is now Jasper and Banff National Parks.

Like Warren, Mary Vaux Walcott continued visiting the region every summer, but typically in the company of her two brothers, who were interested in studying the glaciers. As the only daughter, at age 20 she was expected to look after her father and brothers after the death of her mother. As Laviolette writes, the three siblings had “many summers spent in the western alpine, and for Mary in particular a lifelong commitment of over forty years in the area. To come were the pleasures of mountain rambling and backcountry camping in addition to the study of wildflowers and, on an entirely different scale, glaciers.”

Walcott finally broke this pattern by getting married at age 54 to Charles Doolitte Walcott, who she met in the mountains, and who was the head of the Smithsonian Institution. Together, they intensified their study of native plants, resulting in the publication of the five-volume “North American Wild Flowers” from 1925-1929. The Miller Library has only volume five of this set, with 76 of the 400 original prints, but all are reproduced in the 1953 publication “Wild Flowers of America” and most are part of a splendid new (2022) collection “Wild Flowers of North America.” These later publications are both in the library’s general collection.

While this title suggests a comprehensive collection of the native, flowering plants of the United States and Canada, the emphasis is on the places where the Walcotts’ explored. The Canadian mountains and foothills fill in for much of western America, including our state, while the other emphasis is the Atlantic seaboard. The southwest species are mostly missing, but this is still an impressive work.

Excerpted from the Winter 2022 issue of the Arboretum Bulletin