Imagine a plant carefully and dutifully dried, pressed, and preserved between sheets of paper. Now imagine a room full of cabinets and drawers in which are stacked plant upon plant upon plant in this fashion, over 140,000 dried plant specimens in all. It would be a feat of admirable persistence and curiosity to explore every single specimen. Yet, that is exactly the task Helen Humphreys set out to do in writing

Field Study: Meditations on a Year at the Herbarium.

Over the course of a year, Humphreys does just this. She lingers, wondering aloud about the individuals who went out into the world, found these plants, and committed those plants to lives between sheets of paper. Images and stories throughout Field Study show the reader the variations between plant collectors: how they displayed the plants, the information they included alongside the plant, what kinds of plants interested each collector, and sometimes snippets of biography of the collectors themselves. Humphreys interlaces her own musings on history, culture, and ecological place as such thoughts are inspired by the specimens.

These musings about dead plants collectively create a book about life and death and how we come to understand the losses in our lives. Partway through her project, after spending months thinking about the death of individual plants, Humphreys was forced to reckon with loss in her own personal life when her beloved dog became incurably ill and passed. Much of this book, in turn, became a love-filled meditation on the fleeting joys of her dog and the memories they shared walking everyday in the nearby woods surrounded by beautiful plants. That loss and grief shaped her meditations and sharpened her thinking on what we leave behind us when we pass.

This book is written beautifully and fluidly and Humphreys includes a well-chosen array of photographs and illustrations throughout, making it a delight to read. What at first glance appears to be a light and airy romp through a fascinating world of dried plants, however, ultimately becomes a rather serious examination of the fragility of humanity, personal loss, and what we collectively leave behind. Humphreys initially believed plants were the fragile ones. “And yet,” she says toward the end of her stay, “the flowers still take up their space, still resemble themselves, and I can feel their enduring presence, whereas I am starting to feel like I am the fleeting, temporary thing, that my human life is so brief in comparison to the genetic continuance of this gentian, or this violet.” This is not said without hope, though. As Humphreys understood following her dog’s passing, there is something beautiful to behold in such fragility and impermanence as new insights grow from between the cracks of loss.

Reviewed by Nick Williams in Leaflet for Scholars, Volume 10, Issue 5, May 2023

The National Herbarium of New South Wales, Australia, acts as setting and springboard for Prudence Gibson’s narratives about and descriptions of preserved plants. Gibson holds in admirable tension the wonders of the herbarium and the troubling colonialism that assumed authority over Australia’s plants, collecting them without permission, naming and organizing them by European standards. The question of who owns plants hovers in the background.

The National Herbarium of New South Wales, Australia, acts as setting and springboard for Prudence Gibson’s narratives about and descriptions of preserved plants. Gibson holds in admirable tension the wonders of the herbarium and the troubling colonialism that assumed authority over Australia’s plants, collecting them without permission, naming and organizing them by European standards. The question of who owns plants hovers in the background. The National Herbarium of New South Wales, Australia, acts as setting and springboard for Prudence Gibson’s narratives about and descriptions of preserved plants. Gibson holds in admirable tension the wonders of the herbarium and the troubling colonialism that assumed authority over Australia’s plants, collecting them without permission, naming and organizing them by European standards. The question of who owns plants hovers in the background.

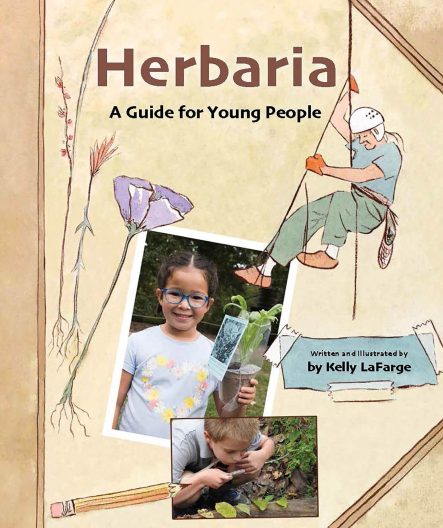

The National Herbarium of New South Wales, Australia, acts as setting and springboard for Prudence Gibson’s narratives about and descriptions of preserved plants. Gibson holds in admirable tension the wonders of the herbarium and the troubling colonialism that assumed authority over Australia’s plants, collecting them without permission, naming and organizing them by European standards. The question of who owns plants hovers in the background. “Herbaria: A Guide for Young People” is a delight. Written and illustrated by Kelly LaFarge, this book blends a mix of drawings and photographs along with lift-up flaps and fold out pages to introduce these critical institutions to an audience that appreciates an interactive experience.

“Herbaria: A Guide for Young People” is a delight. Written and illustrated by Kelly LaFarge, this book blends a mix of drawings and photographs along with lift-up flaps and fold out pages to introduce these critical institutions to an audience that appreciates an interactive experience. Imagine a plant carefully and dutifully dried, pressed, and preserved between sheets of paper. Now imagine a room full of cabinets and drawers in which are stacked plant upon plant upon plant in this fashion, over 140,000 dried plant specimens in all. It would be a feat of admirable persistence and curiosity to explore every single specimen. Yet, that is exactly the task Helen Humphreys set out to do in writing Field Study: Meditations on a Year at the Herbarium.

Imagine a plant carefully and dutifully dried, pressed, and preserved between sheets of paper. Now imagine a room full of cabinets and drawers in which are stacked plant upon plant upon plant in this fashion, over 140,000 dried plant specimens in all. It would be a feat of admirable persistence and curiosity to explore every single specimen. Yet, that is exactly the task Helen Humphreys set out to do in writing Field Study: Meditations on a Year at the Herbarium.