Art Kruckeberg (1920-2016) has a legendary reputation for his research and teaching in botany, and his expansion of that work into the natural history and geology of selected ecosystems. But for gardeners, he is best remembered for his classic “Gardening with Native Plants of the Pacific Northwest,” first published in 1982, followed by a second edition in 1996.

Art Kruckeberg (1920-2016) has a legendary reputation for his research and teaching in botany, and his expansion of that work into the natural history and geology of selected ecosystems. But for gardeners, he is best remembered for his classic “Gardening with Native Plants of the Pacific Northwest,” first published in 1982, followed by a second edition in 1996.

Linda Chalker-Scott is rapidly developing her own renown for books that encourage learning the science behind growing plants. Now she has taken on the major task of guiding the publication of a third edition of “Gardening with Native Plants of the Pacific Northwest.”

This is not just an editorial update. It is a collaboration from different perspectives and eras. Kruckeberg was a professor of botany for nearly four decades at the University of Washington until his retirement in 1989. In his first edition, he acknowledges the help of several individuals that figure prominently in the mid to later 20th century Arboretum, including Brian Mulligan, Roy Davidson, Joe Witt, C. Leo Hitchcock, Sylvia Duryee, and his wife, horticulturist Mareen Kruckeberg, the latter credited with conceiving the concept of this book.

Chalker-Scott is an associate professor of horticulture and extension specialist at Washington State University. Her contributions to the new edition further enhance the reader’s understanding of our native plants in their natural setting, and how to make them thrive in the not-very-natural setting of a typical home garden.

For those familiar with the older editions, the first thing you’ll notice in the new edition is the inclusion of many color photographs, almost one for every text entry. Each photograph has a selection of habitat icons “to help gardeners both visualize the best natural settings for native plants and identify environmental preferences.” For example, a plant may naturally grow in the full sun of a meadow or prairie, or it may need the superb drainage of a rock garden. Plants may be best adapted for wetlands or drylands, or perhaps a woodland or even a seashore. Another symbol marks plants especially successful in restoration projects. The new edition also updates taxonomy, reflecting the recent publication of the 2nd edition of the “Flora of the Pacific Northwest” (see my review in the Spring 2019 issue of “The Bulletin”).

For those new to this book, the breadth of the plant selection may be surprising – we have many garden-worthy natives. The emphasis is on woody plants. Almost all native trees are reviewed in some depth, including those not recommended for a garden setting. In the chapter on deciduous shrubs, ten “choice” species are considered first as the best choices. Much of the writing in these plant descriptions is the voice of Kruckeberg, although I noticed that favored plants are now “our” favorites – the two authors agree on most of the selections.

Chalker-Scott has added a new chapter that brings her signature work on horticultural science to the establishment and maintenance of a garden rich in native plants. She alleviates concerns about using “nativars” – propagated selections chosen for an unusual and desirable trait, such as double flowers or variegation. She also assures the new gardener that it is okay to mix well-behaved exotics into your garden of mostly natives.

One major difference between the second and third editions is the removal of any instructions on how to collect native plants from the wild. Chalker-Scott cautions, “This practice must stop if we are to retain many of our rare, threatened, and endangered species. It’s a better ethical and ecological choice to purchase native plants from reputable nurseries that have propagated and cultivated their plants without endangering native populations.”

Excerpted from the Summer 2019 Arboretum Bulletin

Did you know that skunk cabbage roots look like pale, ropy space aliens? Would you like to learn to make maple syrup from bigleaf maple sap? How about some rose-petal honey for your next tea party?

Did you know that skunk cabbage roots look like pale, ropy space aliens? Would you like to learn to make maple syrup from bigleaf maple sap? How about some rose-petal honey for your next tea party? Roy Martin is a retired University of Washington professor of anesthesiology and bioengineering. He is now pursuing a very different passion, the genus Arbutus, best known locally by A. menziesii, the Pacific Madrone. Eleven species are recognized and in “A Romance with the Exotic Madrona, Alias of the Arbutus,” Martin explores them all, visiting their native ranges in Mexico, western North America, and around the Mediterranean.

Roy Martin is a retired University of Washington professor of anesthesiology and bioengineering. He is now pursuing a very different passion, the genus Arbutus, best known locally by A. menziesii, the Pacific Madrone. Eleven species are recognized and in “A Romance with the Exotic Madrona, Alias of the Arbutus,” Martin explores them all, visiting their native ranges in Mexico, western North America, and around the Mediterranean. There are many rare and unusual trees and shrubs in the Washington Park Arboretum. Standing aside (and sometimes out-competing) these wonderful exotics is the native matrix of trees, especially tall conifers. Perhaps the most iconic of these is the Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii). “Douglas Fir: The Story of the West’s Most Remarkable Tree” is a comprehensive new book by Stephen Arno and Carl Fiedler about this tree native from northern British Columbia to the high mountains of Mexico.

There are many rare and unusual trees and shrubs in the Washington Park Arboretum. Standing aside (and sometimes out-competing) these wonderful exotics is the native matrix of trees, especially tall conifers. Perhaps the most iconic of these is the Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii). “Douglas Fir: The Story of the West’s Most Remarkable Tree” is a comprehensive new book by Stephen Arno and Carl Fiedler about this tree native from northern British Columbia to the high mountains of Mexico. “Native Plants in the Coastal Garden” (1996, revised 2002) by April Pettinger and Brenda Costanzo brings a British Columbia focus to native plant gardening. Essays describe the rise of a late 20th century naturalistic aesthetic in European and American garden design and the supreme suitability of native plants for this look. Many different design aspects are considered, such as container gardening with native plants, and the large role that grasses play in any landscape.

“Native Plants in the Coastal Garden” (1996, revised 2002) by April Pettinger and Brenda Costanzo brings a British Columbia focus to native plant gardening. Essays describe the rise of a late 20th century naturalistic aesthetic in European and American garden design and the supreme suitability of native plants for this look. Many different design aspects are considered, such as container gardening with native plants, and the large role that grasses play in any landscape. Art Kruckeberg (1920-2016) has a legendary reputation for his research and teaching in botany, and his expansion of that work into the natural history and geology of selected ecosystems. But for gardeners, he is best remembered for his classic “Gardening with Native Plants of the Pacific Northwest,” first published in 1982, followed by a second edition in 1996.

Art Kruckeberg (1920-2016) has a legendary reputation for his research and teaching in botany, and his expansion of that work into the natural history and geology of selected ecosystems. But for gardeners, he is best remembered for his classic “Gardening with Native Plants of the Pacific Northwest,” first published in 1982, followed by a second edition in 1996. For Pacific Northwest botanists of all levels, the one-volume book informally known as “Hitchcock” has been standard equipment since its publication in 1973. This work, “Flora of the Pacific Northwest: An Illustrated Manual” by C. Leo Hitchcock and Arthur Cronquist, was intended as a field version of the five-volume flora “Vascular Plants of the Pacific Northwest,” written by the same authors with two additional botanists and two illustrators from 1955-1969.

For Pacific Northwest botanists of all levels, the one-volume book informally known as “Hitchcock” has been standard equipment since its publication in 1973. This work, “Flora of the Pacific Northwest: An Illustrated Manual” by C. Leo Hitchcock and Arthur Cronquist, was intended as a field version of the five-volume flora “Vascular Plants of the Pacific Northwest,” written by the same authors with two additional botanists and two illustrators from 1955-1969.

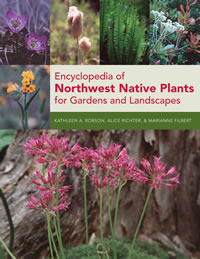

For gardeners, the most important new book of the year will be the

For gardeners, the most important new book of the year will be the