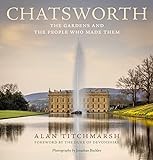

“There is an indefinable quality about the setting of the ‘Palace of the Peaks’ which has always exerted a hold over me and caused my spirits to rise and my heart to flutter” (p.17). Alan Titchmarsh begins his tour of the gardens and people of Chatsworth with this personal response and then compares it to that of Elizabeth Bennett in Pride and Prejudice on first seeing Pemberley, the vast estate of the man she eventually marries.

Both Chatsworth and the fictional Pemberley are in Derbyshire in central England. Chatsworth, the seat of the Duke of Devonshire, consists of 35,000 acres, 105 of which are gardens. Titchmarsh combines a history of the gardens and the gardeners who created them – including famous landscape designers like ‘Capability’ Brown and Joseph Paxton – with accounts of the owners’ family over the centuries. Luscious photographs and historically accurate pictures of family members combine to excellent effect.

Interestingly, the women of the family seem to have been a major, if not the predominant, influence on the gardens. From Bess of Hardwick, who convinced her husband to buy the property in 1549, to Deborah Devonshire in the 21st century, a number of decisions about gardens have been made by women. Titchmarsh tells good stories about all these characters. He enjoys a personal friendship with the current family, calling Deborah “Debo” in the text.

Each of the estate gardens receives a chapter, noting its planting history and challenges over many years. The formal gardens, the rock garden, Arcadia, the arboretum and pinetum, the maze, the glass houses (several!), the follies, and the sculptures all receive admiring descriptions. Titchmarsh also shows how the family has maintained solvency by inviting in the public for carefully chosen events, such as art exhibitions and fairs.

Mostly this book is a work of admiration for both the gardens and the people. Titchmarsh very rarely gives a less than completely positive opinion. Of the monkey puzzle trees, one originally introduced by Paxton, he notes, “Victorian plant collectors . . . seemed to prize oddity as much as beauty” (p. 192). Monkey puzzle trees here in Seattle may reflect the same taste.

Descriptions of visiting royalty and historic cricket matches add variety to this very engaging, as well as beautiful, book.

Review by Priscilla Grundy published in Leaflet for Scholars, volume 11, issue 7, July 2024.