Boria Sax owns a forest. About 80 acres in upstate New York, it’s twice the size of the 40-acre farm once thought enough to support a family. From his investigation of the history of his woods, Sax moves to consider the many ways humans have thought and written about forests over centuries.

Boria Sax owns a forest. About 80 acres in upstate New York, it’s twice the size of the 40-acre farm once thought enough to support a family. From his investigation of the history of his woods, Sax moves to consider the many ways humans have thought and written about forests over centuries.

“Enchanted” can mean either “bewitched” or “charmed.” As Sax points out, forests can instill terror. He cites mythic “figures of terror, which give tangible form to amorphous fears that the forest can inspire” (p. 50), such as the Windigo of Canada and the northern U.S. and the Nandi Bear of Kenya, both of which devour humans.

A forest, Sax reports, “has always been defined far more by its mythic character than by its vegetation” (p. 82). It’s the opposite of civilization, a wilderness, but not necessarily full of trees – often “a sort of indeterminate landscape, with rocks, caves, mountains and trees” (p. 82).

One theme running through this account is the gradual diminishing of forests worldwide. Sax’s own forest is a regrowth after previous use for farming. For most of the United States, no regrowth has occurred – the woods are just gone. Even in classical Greece and Rome timbering began the clearances which have left few wooded areas across Europe and the U.S.

Sax provides chapters on various ways of viewing forests: “The Classical Forest,” “The Forest and Death,” for instance. In “Law of the Jungle” he shows how the word “jungle” appeared first in late 18th century England, applied to forests in the southern hemisphere and associated with Empire: “The word suggested a place of primordial violence and disorder, which was only good for testing one’s manhood and making one’s fortune” (p. 201).

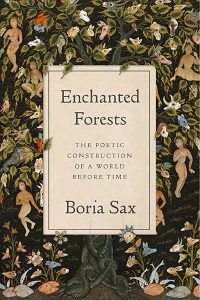

All in all, Enchanted Forests is an enchanting read.

Reviewed by Priscilla Grundy in Leaflet for Scholars, Volume 11, Issue 4, April 2024