James Smith was a lion of the study of botany in 18th century England, when botanizing became a popular activity for both women and men, and the study first entered English university curricula. This biography aims to bring Smith’s accomplishments to twenty-first century attention. Son of a Norwich woolen draper, Smith was smitten with botany at an early age. His astounding accomplishment was to purchase all the botanical specimen collections and manuscripts of Carl Linnaeus, the great Swedish botanist, when Smith was only 25. Then he parlayed this coup into a career in botany which involved a vast output of books and papers, plus hundreds of public and university lectures. And he helped found the Linnaean Society in London, which to this day houses those collections.

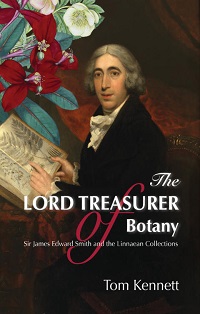

Read from cover to cover, The Lord Treasurer of Botany offers a winsome experience that includes social striving, amazing luck, decades of incredibly hard work, and introductions to multiple English and Continental botanists, most notably Sir Joseph Banks, an early mentor of Smith’s. The Miller Library copy is a reference edition, which means it must be read in the library, so reading cover to cover would require remarkable persistence. Here are some suggestions for shorter activities: If you have 15 minutes, do look at the photographs. This is a beautifully produced book, and the colored prints of plants, though few, are wonderful, as are the portraits and architectural drawings.

If you are a student of early Flora, start with the index and turn to the numerous discussions of books on mostly British plants. The book includes many by other authors, as well as Smith’s.

If you want a sample of the biographical narrative, the opening chapter, “Roots – The Early Life of James Edward Smith,” and the second, “London – the Sale of the Century,” on buying Linnaeus’s collections, are good starts.

None of these shorter stays will give you the ups and downs, the trials of health, the strained generosity of a father who wanted James to earn his own living (which he eventually did), and the long friendships with fellow botanists that the book has to offer. Perhaps they will encourage you to keep coming back for it all.

Published in the October 2017 Leaflet for Scholars Volume 4, Issue 10