When I was very small, my mother often called me “Little Miss Mischief.” It meant I had once again done something wrong, but not terribly wrong, and maybe a little bit cute. I was happy with the title. Elizabeth and Margaretta Morris, the sisters of the title of Catherine McNeur’s book, were not so fortunate. Their mischief was seen as serious; they were challenging the exclusive male 19th century science establishment as they sought opportunity and recognition for their work.

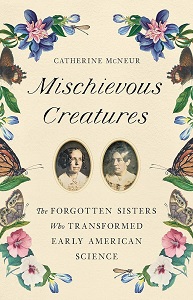

When I was very small, my mother often called me “Little Miss Mischief.” It meant I had once again done something wrong, but not terribly wrong, and maybe a little bit cute. I was happy with the title. Elizabeth and Margaretta Morris, the sisters of the title of Catherine McNeur’s book, were not so fortunate. Their mischief was seen as serious; they were challenging the exclusive male 19th century science establishment as they sought opportunity and recognition for their work.Not travelers, the two women conducted their efforts in botany (Elizabeth) and entomology (Margaretta) in the neighborhood of their Germantown, Pennsylvania home. Neither married, but the family wealth (some, alas, gained from the slave trade) allowed them comfortable single lives together. Their social status enabled them to connect with other scientists in this era when the distinction between professionals and amateurs was blurry.

Collecting plants and insects was central to both their fields of study. Elizabeth, for instance, sent many plant specimens to Asa Gray, the first professor of botany at Harvard, and received some from him in return. Though other scientists collected from the far corners of the earth, the Morrises did their work near home, often along nearby Wissahickon Creek.

Elizabeth resisted publicity for herself. She wrote at least 77 articles about her studies, all anonymous, using initials or such names as “A Friend to Farmers.” Margaretta was different. She studied insects that damaged crops in her neighborhood. In 1836 the Hessian fly, Cecidomyia destructor, was attacking wheat throughout the region. Through close observation, she determined that the current understanding of where on the wheat the flies laid their eggs was faulty. In the spirit of helpfulness she allowed her paper describing her discovery to be read aloud by a male cousin at a meeting of the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia. McNeur’s description of the resulting uproar shows clearly the challenges faced by women scientists.

Margaretta did not back down. Her efforts to gain acceptance led in 1850 to her membership in the American Association for the Advancement of Science. She and the astronomer Maria Mitchell were elected at the same meeting, the first two women members. Margaretta did not attend.

Mischievous Creatures shows in impressive detail how personal contacts, correspondence, and hard work allowed these two women to participate in the development of science in America in the generation after the Revolution. The reader wanders along the creek with Elizabeth and Margaretta as they collect specimens and learns with admiration how they spread their discoveries across the country.

Review by Priscilla Grundy in the Leaflet, Volume 11 Issue 2, February 2024.