In May 2022, I visited the Denver Botanic Gardens. After I tore myself away from the array of tall bearded iris at the peak of bloom, I found nearby different renditions of the traditional rock garden. The rocks were not the smooth, roundish boulders but instead craggy slates, positioned vertically and close together, with only a limited cracks for the plants.

In May 2022, I visited the Denver Botanic Gardens. After I tore myself away from the array of tall bearded iris at the peak of bloom, I found nearby different renditions of the traditional rock garden. The rocks were not the smooth, roundish boulders but instead craggy slates, positioned vertically and close together, with only a limited cracks for the plants.

This was my introduction crevice gardening. This design expands the plant palette for gardeners in the dry, high altitude of the Rockies, but also in our own cool Mediterranean climate, by providing protection from wet winters that kill many plants.

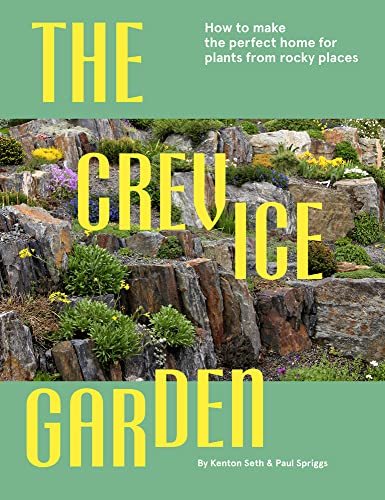

It is appropriate that the new, and almost only, book on this topic – “The Crevice Garden” – has two authors that represent these climate extremes. Kenton Seth is from western Colorado. Paul Spriggs understands the needs of Seattle area gardeners from his crevice garden in Victoria, B.C. Both have careers as gardeners, and discovered their passion for alpine plants in part through backpacking and mountain climbing.

A crevice garden has more rocks than a traditional rock garden, covering at least half of the surface and typically raised to resemble an outcropping of rock. This keeps the plant tops and roots widely separated and in conditions they both prefer. The roots need the deep run with dependable moisture and even temperatures. The leaves and flowers stay dry and free of excessive moisture.

How do you do it? The design process is somewhat complex, but a detailed guide will take you through each step, from calculating how much of each material (rock, soil, dressing) to design and garden placement. And yes, planting! Some 250 plants are recommended, many new to me, but all sound intriguing. Most important is a location where you can watch your (often tiny) treasures from close by.

Several case studies display beautiful examples, including the garden at Far Reaches Farm in Port Townsend, Washington, appropriately titled “alpines in wet winters.” The authors appreciate that “gardening continues to be our most common connection to nature” and hope readers will embrace crevices to explore plants previously only available to keen specialists.

Reviewed by Brian Thompson for Garden Notes: Northwest Horticultural Society, Fall 2022

In the late 19th century in western Canada there were two women who had a lot in common. Mary Schäffer Warren (1861-1939) and Mary Vaux Walcott (1860-1940) were both of Quaker families living in Philadelphia, arguably the center for science and culture in America at the time. They both developed strong interests in the natural world, and developed the skills to paint in watercolors the native plants they found.

In the late 19th century in western Canada there were two women who had a lot in common. Mary Schäffer Warren (1861-1939) and Mary Vaux Walcott (1860-1940) were both of Quaker families living in Philadelphia, arguably the center for science and culture in America at the time. They both developed strong interests in the natural world, and developed the skills to paint in watercolors the native plants they found. The Rock Gardening section of the Miller Library is quite extensive. It contains some of the library’s oldest tomes rich in detail, but the scarcity of newer titles might suggest this form of gardening has gone out of fashion.

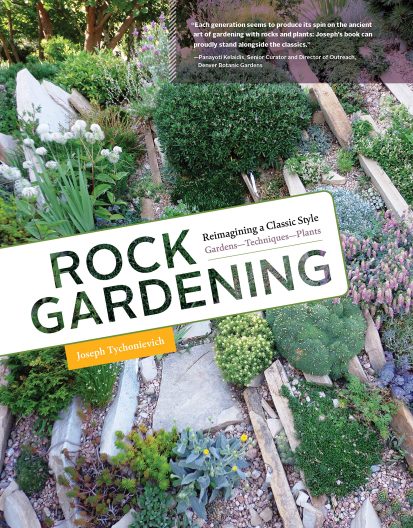

The Rock Gardening section of the Miller Library is quite extensive. It contains some of the library’s oldest tomes rich in detail, but the scarcity of newer titles might suggest this form of gardening has gone out of fashion.