The Victorian fern craze of the late 19th century was noteworthy for its inclusiveness. All classes of English society were engaged, and participants included men, women, and children. One of the leading botanical authors and illustrators of the time was Anne Pratt (1806-1893) who because of a childhood illness was encouraged to pursue botanical illustration. That she did very well, publishing more than 20 books popularizing botany.

Her ”Ferns of Great Britain” (1st edition 1855, the Miller Library has an undated edition from approximately 1871) was one of her major works and was later combined into a six-volume work that included flowering plants, grasses, and sedges. Her writing shows a clear understanding of the science of her subjects, but she also appreciated the pleasures for the amateur: “It is pleasant to see the rambler in the country searching through green lane or by dripping well for the feather fern.”

Excerpted from the Spring 2020 issue of the Arboretum Bulletin

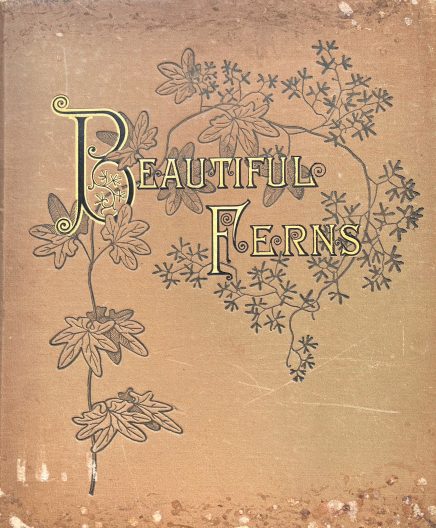

Daniel Cady Eaton (1834-1895) was a rigorous and important 19th century American botanists. He studied at Harvard University under noted botanists Asa Grey and later became a professor of botany and curator of the herbarium at Yale University. His one publication for a general audience was on a grand scale: “Beautiful Ferns from Original Water-color Drawings after Nature” (1882). This is a book to enjoy in the parlor, introducing ferns to an audience unlikely to find them by tromping in the woods. While Eaton’s writing remains academic, he occasionally digresses from his usual rather dry text, for example to describe the Ostrich Fern (Matteuccia struthiopteris) as “one of our finest ferns.”

The illustrations are what makes this book special. The lead artist of these drawings was Charles Edward Faxon (1846-1918); a prominent American botanical illustrator based at Harvard who is best known for illustrating the 14 volume “The Silva of North America” that was written by Charles Sprague Sargent.

Excerpted from the Spring 2020 issue of the Arboretum Bulletin

William Jackson Hooker (1785-1865) was the first director of the Royal Botanic Garden at Kew in Britain, an institution that grew to prominence during his 24 years in that role. He was very interested in all plants and led some of the first plant explorations to isolated places in Europe, including Iceland. He was especially interested in non-flowering plants, with ferns as his favorite.

He wrote several books on ferns beginning in the 1830s, most with botanically detailed and precise descriptions spanning several volumes. In addition to his explorations, he had also had a large herbarium of preserved plant specimens from around the world, so his range was global in scope.

Recognizing the popular interest in ferns, he published for the more casual botanist and gardener “British Ferns” in 1861. He described his subjects as “general favourites with the lovers of Nature and of the horticulturist, in consequence of the extreme beauty and gracefulness of their forms.” Walter Hood Fitch (1817-1892), a protégé of Hooker’s, captured that beauty in hand-colored, lithograph images such as the Osmunda regalis or the “Osmund Royal fern.” Hooker translated “osmund” as meaning domestic peace in Saxon.

Excerpted from the Spring 2020 issue of the Arboretum Bulletin

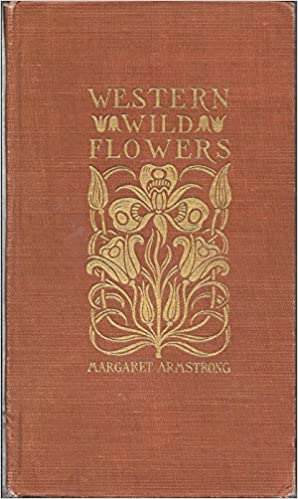

Margaret Armstrong was from the Hudson River valley of New York; she explored the West as part of an extended adventure, but never settled here. She traveled from 1911 to 1914, often with two or three female companions, exploring all of the states west of the Rocky Mountains and into Canada. She was possibly the first woman of European descent to travel to the floor of the Grand Canyon, where she found, described, and illustrated several new plant species. The result of these adventures was the “Field Book of Western Wild Flowers,” published in 1915.

She had considerable training as an artist and is perhaps best known amongst bibliophiles for the over 300 book covers she designed, an art form mostly lost in the 20th century with the development of dust jackets. She also wrote biographies in her 60s, and mystery novels in her 70s! Her schooling was in art, but she understood botany practices very well, collecting and pressing some 1,000 herbarium specimens. Many remain in the New York Botanical Garden herbarium. She lists as her co-author, John James Thornber (1872-1962), professor of botany at the University of Arizona, crediting him and many others (including Alice Eastwood and Julia Henshaw) for assuring the accuracy of her text.

“But it is her illustrations that make the book so appealing,” according to a review by Bobbi Angell in the December 2018 issue of “The Botanical Artist.” These included some 500 pen and ink drawings and almost 50 watercolors, all drawn or painted on site. While there is a glossary of terms and a short set of keys, this book relies more on its illustrations for identification than the others in this review.

Excerpted from the Winter 2020 issue of the Arboretum Bulletin

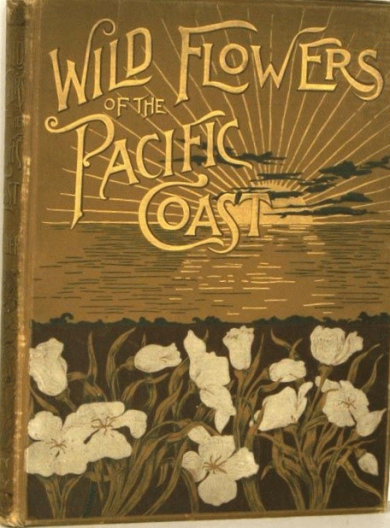

“On the very top of the mound grew this fine salmon blossom, and a few feet away a bed of tall pink grass, the finest I had ever seen. It waved and nodded in the warm breeze, as if inviting me to select its finest bunch to keep company with the pretty white blossoms that had been its neighbors, and from whom it was loth to part company.”

“On the very top of the mound grew this fine salmon blossom, and a few feet away a bed of tall pink grass, the finest I had ever seen. It waved and nodded in the warm breeze, as if inviting me to select its finest bunch to keep company with the pretty white blossoms that had been its neighbors, and from whom it was loth to part company.”

Emma Homan Thayer (1842-1908) wrote these illustrative words, and painted these neighborly plants while visiting Astoria, Oregon in the 1880s. Her “Wild Flowers of the Pacific Coast” (published in 1887) is the earliest guide to the flora of the West Coast in the Miller Library collection. I hesitate to call it a field guide. Instead, it is a series of short travel essays, each tied to a local wild flower. Often the description of the people she encountered is more detailed than that of the flowers. The stories are mostly set in California, but she did make the one visit to Oregon, including a trip by boat from Portland to the mouth of the Columbia River.

In an appendix of “botanical descriptions,” the “fine salmon blossom” is identified as thimbleberry or Rubus nutkanus, but the identity of the grass is not attempted.

Born in New York, Thayer went back to school after her first husband died, attending Rutgers and area art institutions. Late in life, she established a reputation as an author of novels. However, it is for this book, and her similar book, “Wild Flowers of the Rocky Mountains,” that she is best known. While her impressionistic style of illustration lacks the fine detail necessary for certain identification, her books were an introduction, especially for East Coast audiences, to the splendors of the western flora.

Excerpted from the Winter 2020 issue of the Arboretum Bulletin

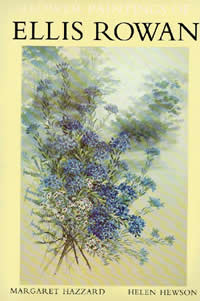

Ellis Rowan (1848-1922) was an Australian painter, specializing in wildflowers in all parts of that country at a time when the native flora was not well-known by European settlers. She was not trained as a botanist, which made her work of limited use in that field. However, the exuberance and abundance (at least 3,000 survive) of her paintings made her very popular. She typically combined flowers with leaves and stems into bouquets, and worked quickly, being able to paint in watercolors and gouache without initial pencil underlay.

Ellis Rowan (1848-1922) was an Australian painter, specializing in wildflowers in all parts of that country at a time when the native flora was not well-known by European settlers. She was not trained as a botanist, which made her work of limited use in that field. However, the exuberance and abundance (at least 3,000 survive) of her paintings made her very popular. She typically combined flowers with leaves and stems into bouquets, and worked quickly, being able to paint in watercolors and gouache without initial pencil underlay.

In “Flower Paintings of Ellis Rowan,” Helen Hewson wrote that her images “evoke the particular quality of the beauty of the Australian bush, a beauty which is vivid, yet also elusive and vulnerable.” Hewson notes the limitations of Rowan’s work for botanists, but recognizes that “her work is so accurate that the specialist can identify a large proportion of the subjects with considerable reliability.”

Excerpted from the Winter 2019 Arboretum Bulletin

Women botanical artists have made many contributions to horticulture and botany. One of these was Wendy Walsh (1915-2014). English by birth, she also lived in Japan and the United States before settling in Ireland in 1958 at the age of 43. She lived and worked there the rest of her long life, providing illustrations for 33 books, many on Irish gardening and native plants.

Women botanical artists have made many contributions to horticulture and botany. One of these was Wendy Walsh (1915-2014). English by birth, she also lived in Japan and the United States before settling in Ireland in 1958 at the age of 43. She lived and worked there the rest of her long life, providing illustrations for 33 books, many on Irish gardening and native plants.

Her masterpieces were “An Irish Florilegium,” published in 1983, followed by “An Irish Florilegium II” in 1987. Each contains beautifully printed copies of 48 watercolor paintings that she drew from nature. Roughly, a third of these plants are native to Ireland, while an Irish botanist or plant collector introduced another third. The rest celebrate the cultivars developed by the many fine nurseries and plant hybridizers of that nation.

E. Charles Nelson, a taxonomist with the National Botanic Gardens Glasnevin in Dublin, wrote the extensive plant notes to both volumes and the introduction to the second. Although he was 36 years younger, he and Walsh became fast friends after meeting at the beginning of this project. Their collaboration led to several more books, including three in the Miller Library.

Excerpted from the Winter 2019 Arboretum Bulletin

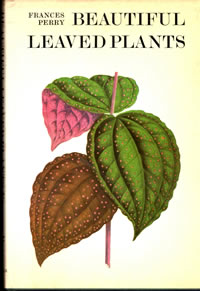

Brent Elliott, retired librarian and historian of the Royal Horticultural Society, declared that Frances Perry’s writing showed “evidence of reading both broader and deeper than that of most garden writers of the time.”

Brent Elliott, retired librarian and historian of the Royal Horticultural Society, declared that Frances Perry’s writing showed “evidence of reading both broader and deeper than that of most garden writers of the time.”

An example of this historical awareness is her book “Beautiful Leaved Plants.” Perry describes 64 house and conservatory plants, popular in the mid-20th century, but chose to illustrate her selections with images by Benjamin Fawcett (1808-1893). Fawcett was a botanical illustrator who used wood engravings, an unusual technique for the time that is particularly effective in capturing the brilliance and subtlety of foliage. The technique is described in a supplemental chapter by Raymond Desmond.

Excerpted from the Winter 2019 Arboretum Bulletin

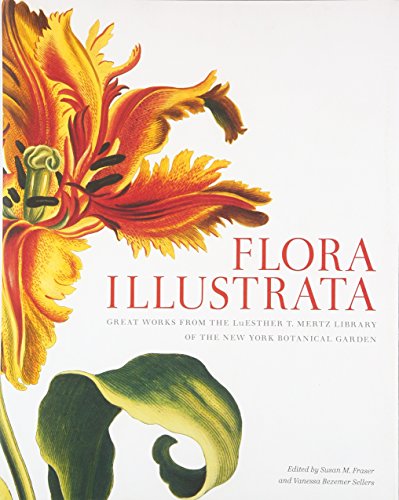

New on the shelves of the Miller Library is a wonderful book, Flora Illustrata, about the LuEsther T. Mertz Library of the New York Botanical Garden. What makes it so wonderful? Why write a whole book about a library? The editors, Susan M. Fraser and Vanessa Bezemer Sellers, answer these questions in their preface. “We hope that Flora Illustrata captures the wonderful experience of spending an afternoon…among the rustling sound of turning pages, the smell of age-worn paper-worlds of wonder emerging from the heavy sheets.”

New on the shelves of the Miller Library is a wonderful book, Flora Illustrata, about the LuEsther T. Mertz Library of the New York Botanical Garden. What makes it so wonderful? Why write a whole book about a library? The editors, Susan M. Fraser and Vanessa Bezemer Sellers, answer these questions in their preface. “We hope that Flora Illustrata captures the wonderful experience of spending an afternoon…among the rustling sound of turning pages, the smell of age-worn paper-worlds of wonder emerging from the heavy sheets.”

Turning the pages of this particular book reveals a wealth of illustrations ranging from the woodcuts of medieval herbals to the brilliant chromolithographs of 19th century seed catalogs. Other images are selected from the Mertz unmatched collection of books on plants of the Americas in their natural setting, often with their attendant butterflies, birds, and other animals.

While it’s hard to tear one’s eyes away from the illustrations, the text, written by experts in botanical and horticultural literature from America and Europe, provides an excellent and engaging history of the writers and illustrators of the books in the collection. It is also an excellent human history as seen from the perspective of botanists, nursery owners, and home gardeners.

For example, Elizabeth Eustis, a specialist in the art history of gardens, describes mid-19th century advertising depictions of fruit trees which intentionally included flaws such as a brown spot on an otherwise perfect apple. “Although a blemish may seem counter-intuitive as a selling point, it could effectively rebut accusations that such plates were unrealistically idealized.” She goes on to explain that even then, “the deceitful peddler was a familiar stereotype…”

Winner of the 2015 Annual Literature Award from the Council on Botanical and Horticultural Libraries.

Published in Garden Notes: Northwest Horticultural Society, Fall 2015

“On the very top of the mound grew this fine salmon blossom, and a few feet away a bed of tall pink grass, the finest I had ever seen. It waved and nodded in the warm breeze, as if inviting me to select its finest bunch to keep company with the pretty white blossoms that had been its neighbors, and from whom it was loth to part company.”

“On the very top of the mound grew this fine salmon blossom, and a few feet away a bed of tall pink grass, the finest I had ever seen. It waved and nodded in the warm breeze, as if inviting me to select its finest bunch to keep company with the pretty white blossoms that had been its neighbors, and from whom it was loth to part company.” Ellis Rowan (1848-1922) was an Australian painter, specializing in wildflowers in all parts of that country at a time when the native flora was not well-known by European settlers. She was not trained as a botanist, which made her work of limited use in that field. However, the exuberance and abundance (at least 3,000 survive) of her paintings made her very popular. She typically combined flowers with leaves and stems into bouquets, and worked quickly, being able to paint in watercolors and gouache without initial pencil underlay.

Ellis Rowan (1848-1922) was an Australian painter, specializing in wildflowers in all parts of that country at a time when the native flora was not well-known by European settlers. She was not trained as a botanist, which made her work of limited use in that field. However, the exuberance and abundance (at least 3,000 survive) of her paintings made her very popular. She typically combined flowers with leaves and stems into bouquets, and worked quickly, being able to paint in watercolors and gouache without initial pencil underlay. Women botanical artists have made many contributions to horticulture and botany. One of these was Wendy Walsh (1915-2014). English by birth, she also lived in Japan and the United States before settling in Ireland in 1958 at the age of 43. She lived and worked there the rest of her long life, providing illustrations for 33 books, many on Irish gardening and native plants.

Women botanical artists have made many contributions to horticulture and botany. One of these was Wendy Walsh (1915-2014). English by birth, she also lived in Japan and the United States before settling in Ireland in 1958 at the age of 43. She lived and worked there the rest of her long life, providing illustrations for 33 books, many on Irish gardening and native plants. Brent Elliott, retired librarian and historian of the Royal Horticultural Society, declared that Frances Perry’s writing showed “evidence of reading both broader and deeper than that of most garden writers of the time.”

Brent Elliott, retired librarian and historian of the Royal Horticultural Society, declared that Frances Perry’s writing showed “evidence of reading both broader and deeper than that of most garden writers of the time.” New on the shelves of the Miller Library is a wonderful book, Flora Illustrata, about the LuEsther T. Mertz Library of the New York Botanical Garden. What makes it so wonderful? Why write a whole book about a library? The editors, Susan M. Fraser and Vanessa Bezemer Sellers, answer these questions in their preface. “We hope that Flora Illustrata captures the wonderful experience of spending an afternoon…among the rustling sound of turning pages, the smell of age-worn paper-worlds of wonder emerging from the heavy sheets.”

New on the shelves of the Miller Library is a wonderful book, Flora Illustrata, about the LuEsther T. Mertz Library of the New York Botanical Garden. What makes it so wonderful? Why write a whole book about a library? The editors, Susan M. Fraser and Vanessa Bezemer Sellers, answer these questions in their preface. “We hope that Flora Illustrata captures the wonderful experience of spending an afternoon…among the rustling sound of turning pages, the smell of age-worn paper-worlds of wonder emerging from the heavy sheets.”