John Albers has highlighted his garden of 20 years in Bremerton and his passion for sustainable gardening practices in two previous books. Now, he turns his attention to a favorite plant group: conifers, especially dwarf and small cultivars. He is very clear in his reasons for writing the book. “Given the horticultural and ecological importance of urban conifers, it is vital that all of us do our part to restore conifers to our urban environment.”

John Albers has highlighted his garden of 20 years in Bremerton and his passion for sustainable gardening practices in two previous books. Now, he turns his attention to a favorite plant group: conifers, especially dwarf and small cultivars. He is very clear in his reasons for writing the book. “Given the horticultural and ecological importance of urban conifers, it is vital that all of us do our part to restore conifers to our urban environment.”

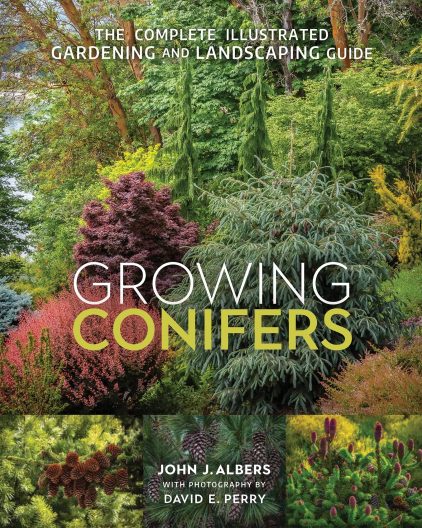

More than just a gardening book, “Growing Conifers” is a good introduction to the botany of conifers. The narrative description of each genus and species gives clues to help with identification, as do the excellent photographs by David Perry. It also explains the origins of the beloved dwarf forms, including many found in the Pacific Northwest, either as mutations in the wild or in nurseries.

The author walks the reader through the process of assessing a garden and developing a design, with the liberal use of suitable conifers. But he doesn’t stop there. He also gives careful instructions for planting and sustainable care of these long-lived plants, and even the basics of propagation.

The design elements also include good companion plants. An example being clematis, especially if they are species that come from lean soil, as Albers believes neighboring plants should share the water needs. However, “sometimes rules can be broken for the sake of a greater good […] for the sake of creating a beautiful garden vignette that warms the heart and soothes the soul.”

Excerpted from the Fall 2021 issue of the Arboretum Bulletin