What species or variety of sumac is used in the spice mix called za’atar? I googled it after reading about it in a Lebanese cookbook written by Mary Laird, but the recipes all just say “sumac berries with salt spray left on them!” Are there different versions of the spice mix in Israel and Arab countries?

There are many variations of za’atar–Syrian, Lebanese, Israeli, Palestinian, etc. I’m going to go off on a bit of a tangent from your question about sumac, because the identity of the main ingredient of za’atar is a bit complicated.

One primary difference, these days, between Israeli, Palestinian, or Jordanian za’atar, and za’atar made anywhere without plant protection laws is that the picking of Origanum syriacum (the main ingredient of za’atar) is prohibited in Israel, the West Bank, and Jordan because it is an endangered plant, and there’s a hefty fine if you’re caught harvesting it in the wild. (Sources: Gil Marks, Olive Trees and Honey 2005, and “A political ecology of za’atar” by Brian Boyd in Environment and Society, 2016).

The word za’atar means ‘hyssop,’ as in the common name for Origanum syriacum, rather than Hyssopus officinalis, which would be too bitter to eat. (Marks says that the plant mentioned in the Hebrew Bible–the Torah–is ezov, which is hyssop, but again, those bible writers weren’t necessarily botanists, so they are believed to have meant O. syriacum.) For more discussion of biblical botanical confusion, see Old Dominion University’s page on bible plants.

Gil Marks’s recipe for za’atar is as follows:

1/4 c. brown sesame seeds

1 c. Syrian oregano (aka white or Lebanese oregano) or alternatively [if you’re not a lawbreaker]: 2/3 c. dried thyme and 1/3 c. dried wild or sweet marjoram

2-4 T ground sumac or 1 T lemon zest

1/2 tsp table salt or 1 tsp kosher salt (optional)

My handwritten recipe which is probably from Claudia Roden’s Book of Middle Eastern Food, 1968, says:

1 cup dried thyme

1 cup sumac

1/4 cup cooked, dried unsalted chickpeas finely pulverized

3 T. toasted sesame seeds

1 T. marjoram

2 T. salt

Bear in mind that Roden is from an Egyptian Jewish family.

There are probably countless regional variations. The za’atar we used to get in a twist of paper from the bread vendors in Jerusalem’s Old City seemed to have very little sumac–it was mostly something like oregano, thyme, sesame seeds, and salt.

And now, back to sumac! Here’s a link to an article on sumac in HaAretz by Daniel Rogov (a cookbook author and food writer). He doesn’t say which species of sumac is the edible one, but most powdered sumac is from Rhus coriaria.

Excerpt:

“Now before we get too far into this, let us make it clear that edible sumac is not to be confused with Rhus glabra which many people know by its common name ‘poison sumac,’ which causes severe itching and skin reactions when touched. Those who have lived in North America are probably familiar with this annoying plant which is a cousin of Rhus toxicodendron (poison ivy).

“In preparing edible sumac, the hairy coating is first removed from the berries, which are then ground to powder-like consistency and used by many in the same way that lemon juice and vinegar are used in the West. The spice is probably at its most popular when making mixtures of za’atar…”

Here is additional information about sumac from Gernot Katzer’s Spice Pages.

For another discussion of za’atar and its ingredients, see the Food-Condiments section of this site from a Society for Creative Anachronism member–it gives you an idea of the diverging opinions about the constituent ingredients.

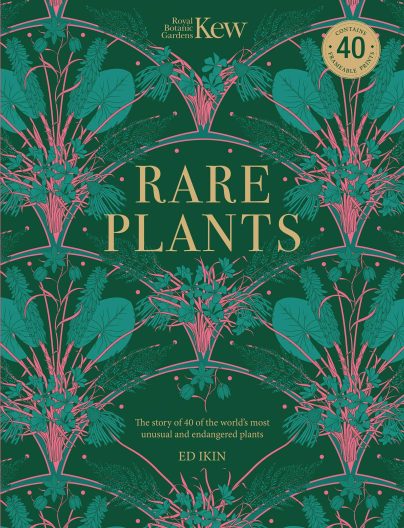

I first glanced through “Rare Plants’ by Ed Ikin for the beautiful plant images: artwork and herbarium specimens from the vast collections of Kew Gardens dating back to the 1700s. These alone would make this book worthwhile, but there is much more. The heart of this book is a collection of essays on 40 plants from around the world that are rare or unknown in the wild. What’s surprising is that many are very familiar to gardeners in the Pacific Northwest.

I first glanced through “Rare Plants’ by Ed Ikin for the beautiful plant images: artwork and herbarium specimens from the vast collections of Kew Gardens dating back to the 1700s. These alone would make this book worthwhile, but there is much more. The heart of this book is a collection of essays on 40 plants from around the world that are rare or unknown in the wild. What’s surprising is that many are very familiar to gardeners in the Pacific Northwest.![[The Quiet Extinction] cover](https://depts.washington.edu/hortlib/graphix/quietextinction.jpg)