Chatsworth: The Gardens and the People Who Made Them

Theodore (Ted) James, Jr. (as writer) and Harry Haralambou (as photographer) were prolific producers of gardening books. Beginning in 1985, they shared a home, dating from 1740, and a garden in Peconic, New York at the east end of Long Island. Their garden was featured in several of their books, many available in the Miller Library. The best in my judgment being “Specialty Gardens.”

James was a writer on a wide range of topics, including for the travel section of the New York Times and comedy material for theater and cabarets. His October 2006 obituary in the Times described him as having “a colorful life. His career took him all over the world. He loved people, parties and telling stories.”

The writing in “Specialty Gardens” showcases this latter skill, weaving fascinating tales of gardens and gardeners from around the world, always complimented by Haralambou’s photographs. James had a keen insight to the fanaticism of a special-interest gardener, and encourages the reader to consider joining their ranks. “Perhaps one of these will interest you, then preoccupy you, and then even addict and possess you. But not to worry, for gardening is a healthy, relatively inexpensive and rewarding pastime.”

A graduate of Princeton University in 1957, the obituary for James in the Princeton Alumni Weekly referred to his life-partner Harry Haralambou. “His dear friend Harry was his partner to the end. The class sends its sympathy to all those who knew this gentle man.” After his partner’s death, Haralambou published his first solo book in 2007, “North Fork Living,” about the community where he and James lived.

Excerpted from Brian Thompson’s article in the Fall 2022 issue of the Arboretum Bulletin

I have been interested in the history of horticulture in the Pacific Northwest from an early age. However, I only recently learned of the work of landscape architects Elizabeth Lord and Edith Schryver and their practice based in Salem, Oregon from 1929 to 1969. Their story is told in compelling detail in The Northwest Gardens of Lord & Schryver, a new book by Valencia Libby.

Elizabeth Lord (1887-1974) was a member of a prominent Salem family; her father was a governor of Oregon. After his death, she became the frequent companion of her mother, from whom she learned about gardening and an appreciation of native plants. Lord was already in her late 30s by the time her mother died, leaving her with an inheritance, but also the need to establish a career. She decided to study at the Lowthorpe School of Landscape Architecture for Women in Groton, Massachusetts, one of the very few institutions for women interested in this field. “It was a program worthy of any modern department of landscape architecture and included an emphasis on horticulture that is rarely found today.”

Edith Schryver (1901-1984) was from the Hudson Valley of New York and also attended Lowthorpe, but at an earlier time than Lord. Her superior skills as a student quickly led to a position with Ellen Shipman in Manhattan, a landscape architecture firm consisting of only women. In June 1927, both Lord and Schryver boarded a ship as part of a trip co-sponsored by Lowthorpe to visit outstanding European gardens.

Meeting shipboard, they quickly became close friends, and spent four months traveling in Europe together, only part of the time with the Lowthorpe group. Upon returning, Lord still had a year of studies to complete, but by early 1929 they moved together to Salem where they shared a home and garden for 45 years. The firm of Lord and Schryver completed designs in Oregon and Washington for about 200 clients, many of them residential gardens, but also public parks, institutional grounds and a variety of other facilities.

Their impact was greater than just the work on specific projects. Early clients included Richard D. and Eula Merrill of Capitol Hill in Seattle. Libby’s research suggests the work of Lord and Schryver influenced the Merrill daughters, Virginia Bloedel and Eulalie Wagner, in their later creations of the Bloedel Reserve and Lakewold Gardens respectively.

Lord and Schryver were noted for their interest in finding new plants and introducing them to gardeners and the local nursery industry. They were familiar with what was being offered on the east coast and they traveled widely. Unlike many in their profession, this “expertise identified them as consummate plantswomen.” They also embraced the innovations in educational outreach, including the new media of radio, speaking on programs intended for home gardeners and especially for women.

We are fortunate that their legacy is preserved today by the Lord & Schryver Conservancy, which maintains the women’s home and garden, known as Gaiety Hollow. Also open to the public in Salem is the historic gardens at Deepwood Museum and Gardens, the former home of Alice Bretherton Brown, a Lord & Schryver client from 1929 until 1968. This is an important book in the history of both landscape design and the development of ornamental horticulture in the region, and it is also a real pleasure to read.

Published in Leaflet for Scholars, Volume 9, Issue 1, January 2022

![[Under Western Skies] cover](https://depts.washington.edu/hortlib/graphix/underwesternskies300.jpg)

An omnibus of garden profiles is a popular format for many horticultural authors, and yet I find Under Western Skies: Visionary Gardens from the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Coast especially engaging. Author Jennifer Jewell brings broad and creative perspectives to what makes each place noteworthy.

Although Jewell wrote the text, she gives first title page credit to Caitlin Atkinson, the photographer, an appropriate decision for a book as sumptuous as this one. The gardens of the geographic range, from the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Coast, have only infrequently been considered before, and the choice of subjects is quite remarkable.

A handful are well-known, such as Heronswood, but even its story is quite different now under the ownership of the Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe. Most were new to me. In Washington State, this includes private gardens in north Seattle, Castle Rock, and Pullman. Others in the region are found in Hood River, Oregon and Tofino, British Columbia.

While I can envision visiting some of the gardens that have public access, this is not a travel guide. By profiling the place, the people, and the plants, each location is presented with a sense of its space in a bigger world. This is done in part by a brief description of the climate, geology, and human history of the indigenous peoples that once dwelt on the land. The photography, rarely showing close-ups, enhances the feeling of lightly defined borders. These gardens, while often providing sanctuary, are not isolated from their surroundings or their past.

Jewell writes in the preface, “Most gardens are a three-part alchemy between the riches and constraints of the natural and/or cultural history of the place, the individual creativity and personality of the gardener, and the gardening culture in which both the garden and the gardener exist.” While I won’t use “Under Western Skies” to plan my next garden touring itinerary, it does give me a better sense of my place and purpose as a gardener, especially in this part of the world.

Published in The Leaflet, Volume 8, Issue 7, July 2021.

Our grandchildren want to make a fairy garden in our front yard. They saw the one down the street which is full of tiny plastic geegaws on astroturf. I’d like to help them do this, but without introducing more plastic into the environment. Can you recommend any resources?

My first suggestion is to invite them on a collecting adventure—in the garden itself, or further afield. They can collect fallen twigs and bark, loose moss, acorns or horsechestnuts (I have fond memories of furnishing a doll’s house with chairs made out of these, with pins for legs and ladderbacks woven with multicolored yarn), interesting seed pods (how about oculus/bull’s eye windows made from translucent Lunaria seed pods?), stones and beachglass—whatever captures their imagination.

There are quite a few books in our Parent/Teacher Resource Collection that have garden craft projects for children, including making dwellings for woodland fairies and trolls (Woodland Adventure Handbook by Adam Dove, 2015), making fairies from flowers and creating houses for them out of twigs, moss, stones and other natural materials (The Book of Gardening Projects for Kids by Whitney Cohen and John Fisher, 2012), making elves, hedgehogs, and tree spirits from clay (Forest School Adventure by Naomi Walmsley and Dan Westall, 2018), and more.

Pacific Northwest author Janit Calvo’s two books (Gardening in Miniature, and The Gardening in Miniature Prop Shop) are aimed at adult readers and include some (but not exclusively) natural materials. Both are worth looking at for ideas that incorporate big-garden design principles scaled down to tiny size. Depending on how much you want to invest in the fairy garden, Calvo also has an extensive plant list. You could even learn bonsai techniques—but that is not really a child-focused approach. It might be best to allow the fairy garden to be as ephemeral and gossamer as its mysterious inhabitants. There are always fascinating materials in nature that may be used to rebuild and remodel the fairy garden as it changes over time.

An aside: if your grandchildren would enjoy a foul-weather indoor fairy garden, they might want to help you design a terrarium. There are quite a few good books on this topic, including Terrarium Craft by Amy Bryant Aiello and Katie Bryant (2011), Plant Craft by Caitlin Atkinson (2016), and The New Terrarium by Tovah Martin (2009).

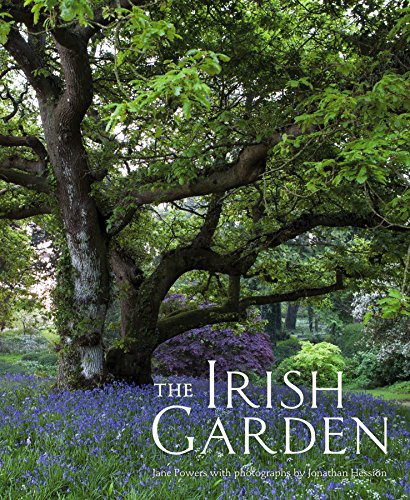

Intrigued by all those Irish gardens with lyrical names? The beauty and glory of these can be found in The Irish Garden, a new, coffee table-worthy book from Jane Powers (writer) and her husband Jonathan Hession (photographer). While its majestic cover and heft will impress your friends, don’t just leave it on the table unopened, because it’s one of the best books on the gardens of a particular region that I know, with the writing, photography, and publication values all top notch.

Intrigued by all those Irish gardens with lyrical names? The beauty and glory of these can be found in The Irish Garden, a new, coffee table-worthy book from Jane Powers (writer) and her husband Jonathan Hession (photographer). While its majestic cover and heft will impress your friends, don’t just leave it on the table unopened, because it’s one of the best books on the gardens of a particular region that I know, with the writing, photography, and publication values all top notch.

The grand gardens are here, but so are the very personal, including Helen Dillon’s place in Dublin. Other gardens are more for a ramble, while most unexpected is a chapter devoted to food gardens. Best of all, these are not formulaic descriptions; Powers wisely leaves the clutter of the often-changing practical details for an Internet search. This book draws you in with both words and images, intrigues you, and makes you want to quit your job and go spend several months in Ireland visiting them all.

Published in Garden Notes: Northwest Horticultural Society, Winter 2016

“The Garden Conservancy is a national, nonprofit organization founded in 1989 to preserve exceptional American gardens for public education and enjoyment.”