Our neighborhood has a small planter area at its entrance. There is no water supply to this area, but a nearby resident is willing to water occasionally. The soil contains much clay. We would like to plant a few drought-tolerant annuals to add color and supplement the more permanent shrubs–such as boxwood–planted in the area. Can you recommend some plant choices? How could we amend the soil to best hold water during the upcoming dry months? Would a commercial product such as “Quench” be of any value, in addition to organic mulches?

I found the following article by Nikki Phipps on GardeningKnowHow.com about drought-tolerant container planting. Here is an excerpt:

“…many plants not only thrive in containers but will tolerate hot, dry conditions as well. Some of these include annuals like marigolds, zinnias, salvia, verbenas, and a variety of daisies. Numerous perennials can be used in a xeriscape container garden such as Artemisia, sedum, lavender, coreopsis, Shasta daisy, liatris, yarrow, coneflower and more. There is even room for herbs and vegetables in the xeriscape container garden. Try growing oregano, sage, rosemary, and thyme. Vegetables actually do quite well in containers, especially the dwarf or bush varieties. There are also numerous ornamental grasses and succulents that perform nicely in containers as well.”

This Brooklyn Botanic Garden’s 2001 article provides a list of drought-tolerant plants for containers.

I had not heard of Quench, but since it is cornstarch-based, it is certainly preferable to the hydrogel and polymer products which are more widely available. I found an article by garden writer Ann Lovejoy in the Seattle P-I (June 3, 2006) about Quench. Here is an excerpt:

With pots and containers, mix dry Quench into the top 12 inches of potting soil in each pot and top off with plain compost. Few roots will penetrate deeper than a foot, so it isn’t very useful down in the depths of really big pots unless you are combining shrubs and perennials.

I would not recommend hydrogels or polymers as a soil amendment. Professor Linda Chalker-Scott of Washington State University has written about these products and their potential hazards. Here is a link to a PDF.

You could consider applying a liquid fertilizer (diluted seaweed-fish emulsion would work) to your containers once every week or two during summer. Here is an excerpt on some general information on container maintenance, from a no longer available Ohio State University Extension article. Excerpt:

“Once planted, watering will be your most frequent maintenance chore, especially if you are growing plants in clay containers. On hot, sunny days small containers may need watering twice. Water completely so that water drains through the drainage hole and runs off. Water early in the day.

“If you incorporated a slow release fertilizer into the potting mix, you may not need to fertilize the rest of the season; some of these fertilizers last up to nine months. You can also use a water-soluble fertilizer and apply it according to the label directions during the season.

“Mulch can be applied over the container mix to conserve moisture and moderate summer temperatures. Apply about one inch deep.

“Depending on the plants you are growing, you will need to deadhead and prune as needed through the season. Monitor frequently for pests such as spider mites. Pests usually build up rapidly in containers.”

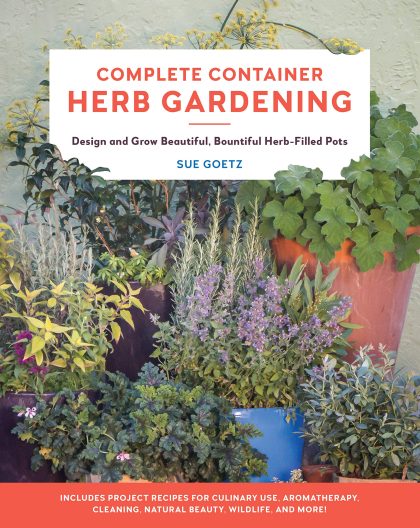

If your garden doesn’t have much space for growing herbs, a container garden might be the answer. I recommend a new book on this topic by western Washington writer, Sue Goetz.

If your garden doesn’t have much space for growing herbs, a container garden might be the answer. I recommend a new book on this topic by western Washington writer, Sue Goetz.