I recently visited the Portland Japanese Garden after many years away, taking a tour in June 2019 as part of a Hardy Plant Society of Oregon study weekend. The focus was the new part of the garden, the Cultural Village, which opened in 2017, but I also made time to explore the earlier areas that date from 1967.

I recently visited the Portland Japanese Garden after many years away, taking a tour in June 2019 as part of a Hardy Plant Society of Oregon study weekend. The focus was the new part of the garden, the Cultural Village, which opened in 2017, but I also made time to explore the earlier areas that date from 1967.

In June 2020, I enjoyed a keynote presentation by Stephen Bloom, the CEO of the Portland Japanese Garden as part of the virtual American Public Garden Association annual meeting. He stressed that the garden is a cultural entity and much more than just a horticultural collection. The Cultural Village, that includes a café, gallery, library, and learning center, is one expression of that vision, allowing the visitor to experience a broad range of Japanese arts and culture.

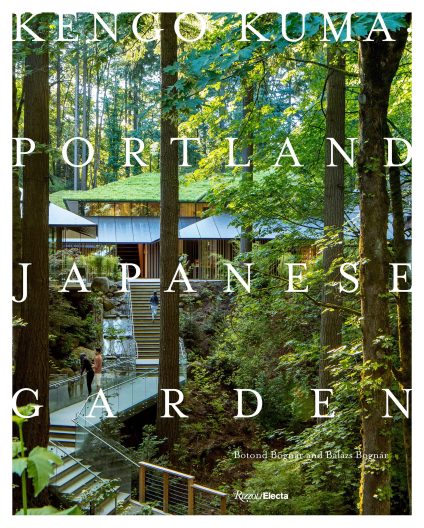

“Kengo Kuma: Portland Japanese Garden” is a substantial new book that tells the story of the Portland Japanese Garden, both old and new, that is written by Botond and Balázs Bognár, father and son Hungarian-American architects. Kengo Kuma is the noted Japanese architect and professor of architecture at the University of Tokyo who was hired to design the Cultural Village.

The authors begin with excellent recounting and appreciation of the original garden, and one of the best summarization I’ve read of both the Shinto and later Buddhist religions in Japan and their impact on Japanese art and design. “The symbiotic relationship between the new and the old alters them both and arguably for the better.”

The older site includes five different styles of Japanese garden design, an unusual trait as gardens in Japan are typically in a single style. These five designs are widely spaced, so that each has its own integrity – qualities well-captured by the images of several photographers.

This book is also the story of how the scope of the garden has grown. CEO Bloom, who was hired in 2005, brought an unusual background as a music educator and non-profit manager. He recognized it is easy to get caught up with the horticulture, the politics, the science – but the garden is really all about people. To hone this focus, he restructured the management, upgrading the Garden Director to Garden Curator, and creating a peer Curator of Culture, Art, and Education.

This made the Cultural Village possible. Kuma writes in his introduction: “I wanted to create a special architecture and place that also did not belong solely to either culture; it would be neither entirely American nor completely Japanese.” This approach is illustrated by the choice of building materials for the new buildings. The interiors are primarily the wood of Port Orford cedar (Chamaecyparis lawsoniana), an Oregon native, crafted by Portland builders, but as “a symbolic counterbalance,” the main doors were made from Japanese wood, constructed in Japan.

Another example of synergy was solving the need for a retaining wall in the courtyard to keep the steep hillside in place. The project team asked the question, why settle for a utilitarian solution? Castle walls are an ancient tradition in Japan, but new castles are rarely built and artisans who maintain existing walls are few. However, Bloom was able to find a stonemason, who was of the 15th generation of a stonemason family, and able to build a new wall in the old tradition, creating a delightful feature that serves a necessary function.

Excerpted from the Fall 2020 issue of the Arboretum Bulletin

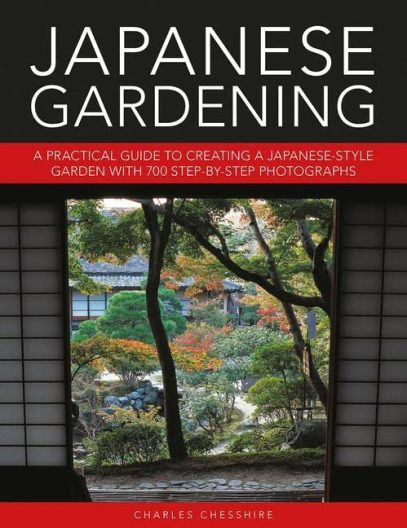

“Japanese Gardening: A Practical Guide” provides a long-needed book on how to apply the principles of Japanese style gardens on a small scale, allowing the incorporation of Japanese garden elements in a home garden.

“Japanese Gardening: A Practical Guide” provides a long-needed book on how to apply the principles of Japanese style gardens on a small scale, allowing the incorporation of Japanese garden elements in a home garden. I recently visited the Portland Japanese Garden after many years away, taking a tour in June 2019 as part of a Hardy Plant Society of Oregon study weekend. The focus was the new part of the garden, the Cultural Village, which opened in 2017, but I also made time to explore the earlier areas that date from 1967.

I recently visited the Portland Japanese Garden after many years away, taking a tour in June 2019 as part of a Hardy Plant Society of Oregon study weekend. The focus was the new part of the garden, the Cultural Village, which opened in 2017, but I also made time to explore the earlier areas that date from 1967. I had the opportunity to visit the Kubota Garden in southeast Seattle last fall as part of a staff enrichment day for the University of Washington Botanic Gardens. It was my first visit in decades, a time in which I have visited many notable public gardens throughout North America and in parts of Europe. For all my travels, I had been overlooking a garden treasure very close to home.

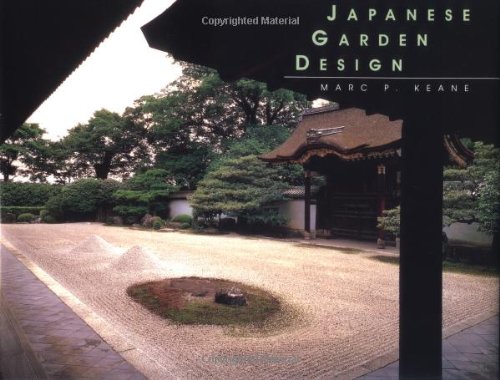

I had the opportunity to visit the Kubota Garden in southeast Seattle last fall as part of a staff enrichment day for the University of Washington Botanic Gardens. It was my first visit in decades, a time in which I have visited many notable public gardens throughout North America and in parts of Europe. For all my travels, I had been overlooking a garden treasure very close to home. Marc Peter Keane has published several books based on his landscape architecture degree from Cornell University and the 18 years he spent in Kyoto designing gardens. “Japanese Garden Design,” his earliest, has stood the test of time.

Marc Peter Keane has published several books based on his landscape architecture degree from Cornell University and the 18 years he spent in Kyoto designing gardens. “Japanese Garden Design,” his earliest, has stood the test of time. For designing your own space in a Japanese style, consider “The New Zen Garden” by Joseph Cali, an American who lived many years in Japan, using his education as an interior designer. In this book, he urges his readers to treat the garden as an extension of the home’s indoor space, and is very practical and systematic in his advice.

For designing your own space in a Japanese style, consider “The New Zen Garden” by Joseph Cali, an American who lived many years in Japan, using his education as an interior designer. In this book, he urges his readers to treat the garden as an extension of the home’s indoor space, and is very practical and systematic in his advice. Yoko Kawaguchi’s book “Japanese Zen Gardens” is excellent source of Japanese gardening history, but with a focus on the dry landscape (kare-sansui) traditions associated with Zen Buddhist temples. These sites bring the history alive with gorgeous photographs by Alex Ramsay and interpretive diagrams. While the dry landscape style may seem static to those outside Japan, Kawaguchi clearly shows an ongoing evolution, including its use for gardens not associated with temples.

Yoko Kawaguchi’s book “Japanese Zen Gardens” is excellent source of Japanese gardening history, but with a focus on the dry landscape (kare-sansui) traditions associated with Zen Buddhist temples. These sites bring the history alive with gorgeous photographs by Alex Ramsay and interpretive diagrams. While the dry landscape style may seem static to those outside Japan, Kawaguchi clearly shows an ongoing evolution, including its use for gardens not associated with temples. Jake Hobson is a European author who moved to Japan. Although now returned to his native England, he writes “Niwaki: Pruning, Training and Shaping Trees the Japanese Way” from his experience in Japan, including working at an Osaka nursery.

Jake Hobson is a European author who moved to Japan. Although now returned to his native England, he writes “Niwaki: Pruning, Training and Shaping Trees the Japanese Way” from his experience in Japan, including working at an Osaka nursery.![[The Japanese Garden] cover](https://depts.washington.edu/hortlib/graphix/JapanesegardenWalker.jpg)

Wybe Kuitert has written two deeply researched books on the history of Japanese gardens. The first, “Themes in the History of Japanese Garden Art” (1st edition 1988, revised 2002 – this later edition is at the Miller Library), is the history from roughly 900 to 1650 CE, concluding when “the practice and theory of garden art became established in a way that does not differ much from our own days.”

Wybe Kuitert has written two deeply researched books on the history of Japanese gardens. The first, “Themes in the History of Japanese Garden Art” (1st edition 1988, revised 2002 – this later edition is at the Miller Library), is the history from roughly 900 to 1650 CE, concluding when “the practice and theory of garden art became established in a way that does not differ much from our own days.”