I’m looking for information about whether cultivars of native plants are considered native. I work as a landscape designer and often have to use native plants around the county to follow regulations.

There is no definitive answer to your question, and the notion of what is native is fraught with complications. You may have encountered the recently coined term ‘nativar,’ used to describe cultivated varieties of native species. In the most recent edition of Arthur Kruckeberg’s Gardening With Native Plants of the Pacific Northwest, updated by Linda Chalker-Scott (2019), there is a useful explanation of the differences between natives, varieties, cultivars, and hybrids. In answer to the question of whether cultivars may be used in native gardens, Chalker-Scott says that cultivars can be “naturally occurring forms that are discovered and cultivated for nursery trade, or they may be developed through plant breeding programs.” As to whether cultivars should be used in native gardens, she states that “native purity may be important in special landscape situations such as ecological restoration,” but there is no reason not to use cultivars in home gardens.

Chalker-Scott has written extensively on the use of native plants compared with introduced ones. Her Garden Professors blog post “Native vs. nonnative – can’t we all just get along?” attempts to debunk the tendency “to demonize noninvasive, introduced plants in the absence of a robust body of evidence supporting that view.” Susan Harris of the Garden Rant blog also discussed Chalker-Scott’s writing on the subject, “starting with definition of ‘native’. According to Linda, that here-before-the-Europeans thing isn’t as clear-cut as we think. For example, the Ginkgo biloba is considered an Asian plant, yet its fossils can be found in Washington State, where it grew millions of years ago. […] She lists the well-known benefits (see any source on the subject), but also the missing caveats in almost all discussions of native plants: ‘Unfortunately, many of us live in areas that no longer resemble the native landscapes that preceded development…The combination of urban soil problems, increased heat load, reduced water, and other stresses mean that many native species do not survive in urban landscapes. … When site conditions are such that many native plants are unsuitable, the choice is either to have a restricted plant palette of natives or expand the palette by including nonnative species.'”

The 2019 article “Native vs. ‘nativar’ – do cultivars of native plants have the same benefits?” (from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign Extension blog ) explores how we define native, and what the differences are for native pollinators when faced with cultivated varieties. The answer depends on the nature of the variation: plants bred for different colored foliage than the plain species, for instance, may affect whether or not insects will be attracted to it. Benjamin Vogt’s thoughtful and well-illustrated article, “Navigating Amid Nativars” (Horticulture magazine, July/August 2022) encourages us to think in a nuanced way about native plant cultivars. Some may be good for pollinators, but “the more we alter a plant, the more we risk reducing its benefits to the fauna around us.” The benefits and deficits of nativars are not straightforward. He suggests keeping in mind that our home landscapes “are not actually restoring nature [..] in the same way we would in a prairie or forest. Those ecosystems require a larger set of more complex rules and goals.” If your aim is to do the most you can to make a garden function like an ecosystem, “use as many open-pollinated, straight species as you can and […] create thick layers with significant plant density that will prove more resilient to a variety of urban and climatic pressures.”

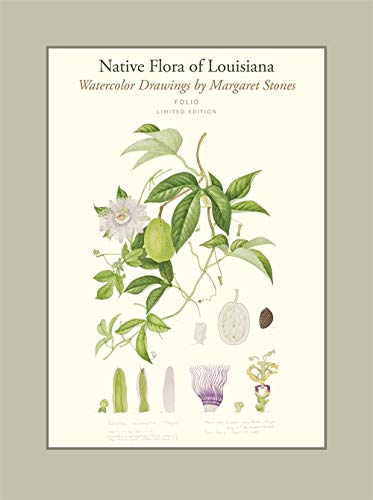

Margaret Stones (1920-2018) was born in Australia but spent much of her career in Britain. She was the principal contributing artist to Curtis’s Botanical Magazine from 1958-1981 and illustrated three gardening books by the Scottish plant explorer E. U. M. Cox and his son Peter Cox in the 1950s and 1960s. She is perhaps most famous for illustrating the six-volume “The Endemic Flora of Tasmania” published between 1967 and 1978.

Margaret Stones (1920-2018) was born in Australia but spent much of her career in Britain. She was the principal contributing artist to Curtis’s Botanical Magazine from 1958-1981 and illustrated three gardening books by the Scottish plant explorer E. U. M. Cox and his son Peter Cox in the 1950s and 1960s. She is perhaps most famous for illustrating the six-volume “The Endemic Flora of Tasmania” published between 1967 and 1978.![[The Quiet Extinction] cover](https://depts.washington.edu/hortlib/graphix/quietextinction.jpg)