We recently moved into an old house with a huge fig tree in

the back. We just missed this whole season’s crop because I was waiting

for them to turn brown but the birds got them all first. Then I saw some

green figs for sale in the grocery store and it appears that some

varieties don’t turn brown. Is this true or did mine not ripen? Also, the tree is probably close to 30′ and we’d like to add a screened-in porch under part of it. I’d really like to keep the tree and a good

bit of fruit but I want it to grow more in the other direction. I’ve read

that “hard pruning” is encouraged, but does that really mean cutting down

a thirty foot tree? Do I need to do it in stages? What’s the best size

and shape and how do I get it there?

There are different types of figs, and some are green, some are brown,

some are purple, as the images on the commercial site of Adriano’s Fig Trees illustrate.

Figs should be picked when ripe, as they will not ripen off the tree. The California Rare Fruit Growers site has good general

information on growing figs.

As for pruning, the best time to prune is late winter/early spring. To

control height, open the center of the tree and remove any dead wood or

drooping branches. I don’t think radical pruning is the standard practice

in maintaining a fig tree. University of Arizona article on growing figs describes pruning practices for several different varieties of fig.

Most pruning is best done when the tree is dormant, during the winter

when it is leafless. Even during the spring and summer, however, you can

start by removing all branches and stems that are obviously dead.

The rest depends on how your tree is growing (single trunk or

multi-stemmed), what kind of results you would like (how large, small or

what shape) and how long the tree has been unpruned. Our rule of thumb is

to go by thirds. Remove about a third of the wood that you would

eventually like to have gone. On multi-stemmed figs that are becoming

large, we recommend selecting a few oversized stems and thinning those

out to the ground, rather than “heading” all the branches to stubs. Let

the tree rest for the summer and see what new growth appears. We

recommend keeping fig trees small enough that all the fruit can be easily

reached from the ground but in some areas of the south and southwest,

folks treasure the deep shade of the larger figs. The final shape and

size are up to you.

A 2006 article by Bunny Guinness in the British newspaper the Telegraph also describes how to prune an older fig tree. Excerpt:

“Figs really are a lazy man’s fruit and, once they have had their

formative training, mature trees or wall-trained shrubs do not need much

attention apart from some replacement pruning. This involves removing one

of the seven or so main limbs every three to four years in March or

April, to stop the whole bush becoming too old and unproductive. Apart

from this, providing you have the wall space, you can leave well alone. I

have seen many such ‘neglected’ plants, and they still fruit well,

although perhaps not as well as they might.

“On the other hand, if you want to maximize your crop (assuming it is

against a wall), buy a copy of Clive Simms’s Nutshell Guide to Growing

Figs (Orchard House) to see how to fan train it

against a wall–it is not hard. Once you have established an approximate

fan of branches, you can start the ongoing pruning regime.

“Firstly, remove any weak branches in winter. Then, in April, remove the

very tips of the main branches, above the developing figs. This will

encourage side shoots, which are summer-pruned by cutting back in June to

about four leaves. This technique can almost double the crop and bring it

forward by a couple of weeks. Do not be tempted to cut back hard in

winter, unless you don’t mind forgoing a lot of your crop–this will

cause lots of new growth but little fruit.”

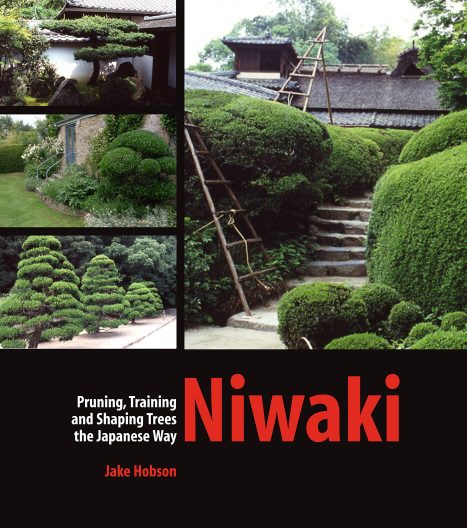

Jake Hobson is a European author who moved to Japan. Although now returned to his native England, he writes “Niwaki: Pruning, Training and Shaping Trees the Japanese Way” from his experience in Japan, including working at an Osaka nursery.

Jake Hobson is a European author who moved to Japan. Although now returned to his native England, he writes “Niwaki: Pruning, Training and Shaping Trees the Japanese Way” from his experience in Japan, including working at an Osaka nursery.