Perhaps the most iconic of trees, the ginkgo has long deserved a book of its own. This has also been a long-time goal of Peter Crane, a former director of Kew Gardens, who wrote “Ginkgo: The Tree That Time Forgot.” Much of his book discusses the fossil records of the ginkgo, its one time vast range around the globe, and its subsequent diminishing to near extinction.

This story has a link to our region in its reference to the Ginkgo Petrified Forest State Park near Vantage, Washington, which is especially unusual because of the presence of preserved wood. Most fossil sites only have leaves. Even closer to home, ginkgo is the iconic plant for China in the Entry Gardens of Pacific Connections and there is also a fine example at the parking lot entry of the Graham Visitor Center.

The research shows that the genus Ginkgo, now monotypic, once had several species, and several closely related genera. No close relatives are living today. Despite considerable interest in this topic, “…exactly how ginkgo fits into the grand scheme of plant evolution remains elusive.”

While these stories are important, Crane is at his best in his accounts of the cultural impacts of this tree on humans. This is perhaps because he and his family lived near the “Old Lion” at Kew, a ginkgo planted in 1761 and considered the oldest in the United Kingdom. There are many specimens that mark temples and other holy places throughout China and Japan, the only places it has survived from antiquity. Since its rediscovery and revival in western cultures, it has also become an important landmark in North America, for example the giant specimen that Frank Lloyd Wright built his home around in Oak Park, Illinois.

The awe this tree inspires is captured in the author’s description of Hōryō Ginkgo in northern Honshu in Japan. “It is approached with reverence down an aisle of closely spaced, moss-covered stepping-stones. Local people visit it regularly…they explain the tree’s legends to local schoolchildren, and they work to spread word of its importance. This tree was a friend to their grandparents; it will probably also be a friend to their grandchildren.”

The ginkgo’s role in human lives continues to evolve. The male ginkgo, free of odorous fruit, has become a popular street tree in urban centers throughout the temperate world. Many consider roasted ginkgo nuts to be a delicacy and the seeds have been used in traditional Asian medicine for centuries, despite a low level of toxicity. More recently, and mostly in the West, the leaves have become the focus of potential medicinal benefits, with an extract considered to be a memory enhancer.

Excerpted from the Summer 2016 Arboretum Bulletin.

The term “steppes” may conjure up images of Russia and the wide plains of central Asia, but “Steppes: The Plants and Ecology of the World’s Semi-Arid Regions”, a new book published by the Denver Botanic Gardens, brings this exotic image much closer to home.

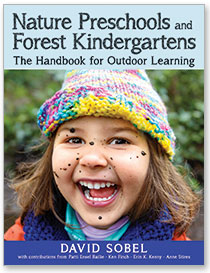

The term “steppes” may conjure up images of Russia and the wide plains of central Asia, but “Steppes: The Plants and Ecology of the World’s Semi-Arid Regions”, a new book published by the Denver Botanic Gardens, brings this exotic image much closer to home. Reading David Sobel’s latest book feels like attending a national conference on outdoor early childhood education. Each chapter draws on the expertise and experience of key decision-makers working with young children in nature programs all over the country. The format also gives a sense of history and progress over time, with Sobel’s journal entries from his work in outdoor education in the 1970s and his personal parenting journals from the 1990s presented alongside his contemporary research and observations from visits to today’s outdoor preschools.

Reading David Sobel’s latest book feels like attending a national conference on outdoor early childhood education. Each chapter draws on the expertise and experience of key decision-makers working with young children in nature programs all over the country. The format also gives a sense of history and progress over time, with Sobel’s journal entries from his work in outdoor education in the 1970s and his personal parenting journals from the 1990s presented alongside his contemporary research and observations from visits to today’s outdoor preschools.