The first comprehensive flora of the state of Oregon in over 50 years is in progress with the first of three volumes released this summer. This volume is focused on ferns and their kin, conifers, and monocots, but in addition to the expected and detailed plant descriptions and range maps, there is an excellent introduction to the wide diversity of ecosystems in this state, including the Siskiyou Mountains. “Rare plants in the region are concentrated on serpentinite and dunite and soils derived from these heavy-metal rich rocks. Many of these plants are narrow endemics of only southwestern Oregon, but several have ranges that extend into adjacent northwestern California.”

Taking a cue from field guides, “Flora of Oregon” includes a list of recommended places throughout the state to see the greatest number of plant species. Highlights in the Siskiyou Mountains ecoregion include the Table Rocks (although beware, there are geographical features elsewhere in Oregon that also go by this name), the trail through the Rogue River canyon downstream from Grants Pass, and the Mt. Ashland-Siskiyou Peak ridge that “is home to a unique flora that is transitional between California and Oregon floras.”

If you’d prefer to explore nature from the comfort of your couch (or one of the comfortable chairs in the Miller Library), you might vicariously go botanizing by reading the biographies of a dozen or so prominent Oregon botanists included in the introduction. I found the story of Lilla Leach (1886-1980) most interesting, especially her discovery of the Siskiyou Mountains endemic and monotypic genus Kalmiopsis leachiana.

In 1930, she was walking ahead of her husband John Leach, who was also an active field botanist, and their pack burros when “‘suddenly I beheld a small patch of beautiful, low growing, deep rose-colored plants. Because of their beauty, I started running and dropped to my knees.'” May we all have such exciting moments when exploring for our native plants!

Excerpted from the Winter 2016 Arboretum Bulletin.

In defining the Pacific Northwest for the purposes of collecting books for the Miller Library, we have included the portion of California north of the San Francisco Bay area. That inclusion was confirmed for me when visiting Mendocino County this past summer where I especially enjoyed the Mendocino Coast Botanical Garden, which includes an arboretum of conifers and a closed-cone pine forest.

A new book in the Miller Library collection, “Wildflowers of Northern California’s Wine Country & North Coast Ranges,” highlights the herbaceous natives of this area and fills in another gap in the field guides to our defined region.

Author Reny Parker has solid northwest credentials, having learned to love the outdoors from outings with her father in central Oregon and British Columbia. She is primarily a photographer and this book includes an elegant collection of close up photos arranged by colors and ordered so that species that resemble each other are together for easy comparison. At the end, there is a section for ferns, grasses, and woody plants and maps of “Hot Spots for Wildflowers”. Since this book includes Marin, Napa, and Sonoma counties, it would be the perfect companion for a winery tour, giving you a chance to clear your head between tastings.

Excerpted from the Winter 2016 Arboretum Bulletin.

Mount Shasta in Northern California has an interesting flora, and also has one of the most interesting field guides to that flora. “Mount Shasta Wildflowers” uses the watercolor paintings of Edward Stuhl (1887-1984) for its images. Stuhl was born in Budapest and studied art in Austria and Germany before coming to the United States to work in stained glass. He quickly left that pursuit and ended up in northern California where he spent the rest of his long life painting the native flowers that he grew to love.

Four authors combined forces to bring this book into being, it appears primarily to make the Stuhl art collection, housed at California State University Chico, better known. They have also spent considerable effort to make this a worthy field guide by ensuring the taxonomy is up to date, providing a comprehensive and updated plant list for Mount Shasta, and giving guidance – through a series of recommended hikes – to finding each of the subjects.

A detailed visual index, with roughly inch-square reductions of the images arranged by colors, is a charming way to find your way through the book, but my favorite feature is the illustrated glossary with examples of numerous flower and leaf parts all taken from Stuhl’s paintings.

Excerpted from the Winter 2016 Arboretum Bulletin.

Michael Edward Kauffmann presents an excellent introduction to the ecology and the geology of the Klamath Mountain region in his book “Conifer Country.” He also helped me understand the names of the mountains. The Klamath Mountains include nine distinct sub-ranges beginning in the north with the Umpqua Valley of Oregon and reaching south to the Yolla Bolly Mountains west of Red Bluff, California.

The Siskiyou Mountains sub-range is by far the biggest, and includes all of the Oregon portion of the Klamath Mountains and a sizable part of California, especially closer to the coast. But to complicate matters, the coast has its own, separate mountains (the North Coast Range).

Confused? The maps that Kauffmann has drawn for his book will help tremendously. The main take-away is that this is an extremely rich area for botanists. “The Klamath-Siskiyou Ecoregion is world renowned for being a crossroads for biodiversity, representing one of the most species rich temperate coniferous forests on Earth.”

Following this engaging introduction, the author profiles the 35 conifer species of this region, including excellent range maps and photos, along with text that is suitable for the amateur to tell these often similar trees apart. These are followed by a series of suggested hikes, all geared for seeing the most of conifers, the richest being the so-called Miracle Mile. This square mile near Little Duck Lake, about 50 miles west of Mount Shasta, has over 400 vascular plant species including 18 different conifer species!

Excerpted from the Winter 2016 Arboretum Bulletin.

If you have enjoyed a hike up one of the Table Rocks in Southern Oregon, you might be interested in “Flowers of the Table Rocks” by Susan K. MacKinnon. These distinctive geological features in the Rogue River Valley just north of Medford are the likely remnants of a lava flow some seven million years ago. Erosion has left two plateaus standing well above the surrounding valley, and the mostly open and grassy tops are home to over 300 plant species, including 200 wildflowers.

This self-published book primarily speaks through its numerous close-up photos, with enough detail to engage the serious field botanist, but presented by the author/photographer to help anyone who just wants to know the names of the flowers. “I hope that some of the photos will inspire in even the casual reader the sense of awe, excitement and discovery that I experienced in studying the flowers.”

Much of the text discusses recent changes in nomenclature and a table in the appendices records these changes. Other tables show times of flowering, common names, and – perhaps the most interesting – the meaning or source of the scientific names.

Excerpted from the Winter 2016 Arboretum Bulletin.

The author of three more conventional field guides to wildflowers, Elizabeth L. Horn makes “Oregon’s Best Wildflower Hikes: Southwest Region” about hikes to see wildflowers. Throughout she uses only common names, but this helps move you along the trail.

“Both Table Rocks are known for their colorful displays of springtime wildflowers. We hiked the area in both early April and early May and found the wildflowers breathtaking.” Lest this sound a little too idyllic, she warns that the trail rating is “strenuous” and that “poison oak and ticks are plentiful, so stay on the trail.”

While this is not a field guide, many prominent species are highlighted with close-up photos (all by the author) with interesting facts that make each distinctive. Detailed directions and GPS coordinates will help you find the trailhead while close-up maps will help along the trail.

Excerpted from the Winter 2016 Arboretum Bulletin.

“Wildflowers of Southern Oregon” was written by John Kemper, a natural history writer who settled in Medford, and recognized the need for a simple guide to the native and naturalized flowers of the region. He’s also a skilled photographer, and even though each entry has only a single image, this will work well for most readers. Plants are divided by color and by families within colors.

In the forward, Frank Lane, retired chairman of the Biology Department at Southern Oregon University in Ashland, writes that until this book was written, “there was no book for beginners covering all of Southern Oregon.” The author includes a short list of best hikes and to help with planning, each image includes a description of the location and time of year when the photograph was taken.

Excerpted from the Winter 2016 Arboretum Bulletin.

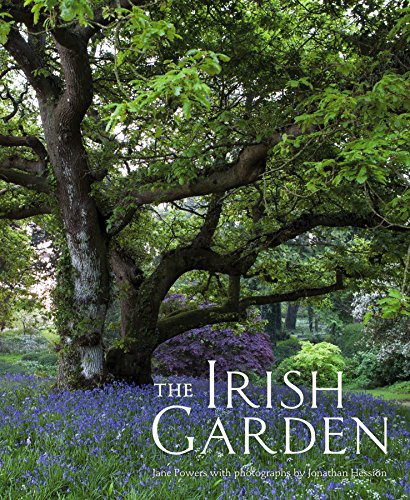

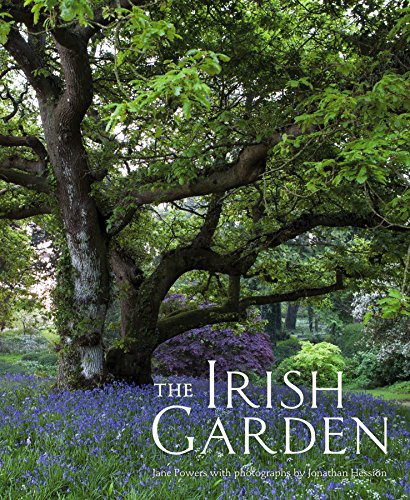

Intrigued by all those Irish gardens with lyrical names? The beauty and glory of these can be found in The Irish Garden, a new, coffee table-worthy book from Jane Powers (writer) and her husband Jonathan Hession (photographer). While its majestic cover and heft will impress your friends, don’t just leave it on the table unopened, because it’s one of the best books on the gardens of a particular region that I know, with the writing, photography, and publication values all top notch.

Intrigued by all those Irish gardens with lyrical names? The beauty and glory of these can be found in The Irish Garden, a new, coffee table-worthy book from Jane Powers (writer) and her husband Jonathan Hession (photographer). While its majestic cover and heft will impress your friends, don’t just leave it on the table unopened, because it’s one of the best books on the gardens of a particular region that I know, with the writing, photography, and publication values all top notch.

The grand gardens are here, but so are the very personal, including Helen Dillon’s place in Dublin. Other gardens are more for a ramble, while most unexpected is a chapter devoted to food gardens. Best of all, these are not formulaic descriptions; Powers wisely leaves the clutter of the often-changing practical details for an Internet search. This book draws you in with both words and images, intrigues you, and makes you want to quit your job and go spend several months in Ireland visiting them all.

Published in Garden Notes: Northwest Horticultural Society, Winter 2016

As a new graduate of the University of Washington’s Library and Information Science Master’s program, I began volunteering at the Miller Library in July 2011. I had some experience in academic libraries, and had worked as a student assistant in the UW’s Natural Sciences Library. After I began volunteering, I started reading and checking out several books on fruit and vegetable gardening. The books were great, and really helped me learn how to grow food.

As a new graduate of the University of Washington’s Library and Information Science Master’s program, I began volunteering at the Miller Library in July 2011. I had some experience in academic libraries, and had worked as a student assistant in the UW’s Natural Sciences Library. After I began volunteering, I started reading and checking out several books on fruit and vegetable gardening. The books were great, and really helped me learn how to grow food.

I decided to add chickens to my urban garden, making it a small urban farm. One of the best books that helped me prepare for my chickens was “Reinventing the Chicken Coop” by Kevin McElroy and Matthew Wolpe. The book contains 14 coop designs. It covers chicken coop essentials including space requirements, roosts, ventilation, and nesting boxes. This information was very helpful to me as I was learning what it would take to keep chickens in my yard. In the Coop-Building Basics chapter the authors explained, “One of our goals for this book was to keep things simple, using ordinary shop tools and building with similar materials and repeatable processes as much as possible” (p. 21). In the end, my husband and I built our coop using their design, SYM, which is “much more than a chicken coop; it’s a symbiotic urban farming system” (p. 106). This was exactly what we needed. The step by step instructions were easy to follow and it didn’t take too long to build this simple yet stable coop for our new flock. “Reinventing the Chicken Coop” is a great resource for building chicken houses with ease and low cost. Most pre-built coops cost twice as much as the materials used for building your own coop. I enjoyed the collection of contemporary designs and my chickens love their little home in my city backyard.

Now, I am a librarian at the Miller Library, with two years of experience in chicken husbandry and a growing knowledge of year-round vegetable and fruit gardening. I take pleasure in being knowledgeable on these subjects and plan to continue learning, expanding my understanding of urban farming.

Published in the November 2015 Leaflet Volume 2, Issue 11.

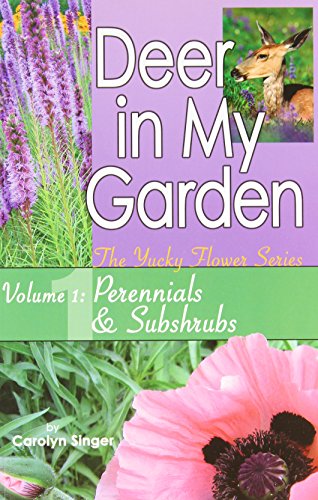

Grass Valley, California is on the outer rim of our region, but the resident gardening columnist Carolyn Singer is worth knowing about, especially for gardeners in the foothills of the Cascades. She is very experienced with the ravages of deer, and address this concern in two books. “Deer in My Garden” (2006), was largely written while the author spent the summer of 2005 in Seattle and focuses on perennials and subshrubs. “Deer in My Garden: Volume 2” (2008) considers the impact on groundcovers and garden edge plants.

Grass Valley, California is on the outer rim of our region, but the resident gardening columnist Carolyn Singer is worth knowing about, especially for gardeners in the foothills of the Cascades. She is very experienced with the ravages of deer, and address this concern in two books. “Deer in My Garden” (2006), was largely written while the author spent the summer of 2005 in Seattle and focuses on perennials and subshrubs. “Deer in My Garden: Volume 2” (2008) considers the impact on groundcovers and garden edge plants.

Both books are part of “The Yucky Flower Series,” honoring the advice of her then 3-year-old grandson: “The deer wouldn’t eat yucky flowers!” So that is what she planted. Her deer-resistant recommendations are based on her own experience, or those of gardeners who grew trial plants for her, knowing that in the interest of science (or cervid consumer selection), the trial plants might disappear.

While yucky to deer, the selected plants are all quite lovely to gardeners and would make many other recommended plant lists. Most are drought tolerant and adapted to a wide temperature range. Best of all, the author enthusiastically rates the maintenance requirements of most as “EASY!” to “VERY, VERY EASY!” Deer or no deer, these are great garden plants.

Excerpted from the Spring 2015 Arboretum Bulletin

Intrigued by all those Irish gardens with lyrical names? The beauty and glory of these can be found in The Irish Garden, a new, coffee table-worthy book from Jane Powers (writer) and her husband Jonathan Hession (photographer). While its majestic cover and heft will impress your friends, don’t just leave it on the table unopened, because it’s one of the best books on the gardens of a particular region that I know, with the writing, photography, and publication values all top notch.

Intrigued by all those Irish gardens with lyrical names? The beauty and glory of these can be found in The Irish Garden, a new, coffee table-worthy book from Jane Powers (writer) and her husband Jonathan Hession (photographer). While its majestic cover and heft will impress your friends, don’t just leave it on the table unopened, because it’s one of the best books on the gardens of a particular region that I know, with the writing, photography, and publication values all top notch. As a new graduate of the University of Washington’s Library and Information Science Master’s program, I began volunteering at the Miller Library in July 2011. I had some experience in academic libraries, and had worked as a student assistant in the UW’s Natural Sciences Library. After I began volunteering, I started reading and checking out several books on fruit and vegetable gardening. The books were great, and really helped me learn how to grow food.

As a new graduate of the University of Washington’s Library and Information Science Master’s program, I began volunteering at the Miller Library in July 2011. I had some experience in academic libraries, and had worked as a student assistant in the UW’s Natural Sciences Library. After I began volunteering, I started reading and checking out several books on fruit and vegetable gardening. The books were great, and really helped me learn how to grow food. Grass Valley, California is on the outer rim of our region, but the resident gardening columnist Carolyn Singer is worth knowing about, especially for gardeners in the foothills of the Cascades. She is very experienced with the ravages of deer, and address this concern in two books. “Deer in My Garden” (2006), was largely written while the author spent the summer of 2005 in Seattle and focuses on perennials and subshrubs. “Deer in My Garden: Volume 2” (2008) considers the impact on groundcovers and garden edge plants.

Grass Valley, California is on the outer rim of our region, but the resident gardening columnist Carolyn Singer is worth knowing about, especially for gardeners in the foothills of the Cascades. She is very experienced with the ravages of deer, and address this concern in two books. “Deer in My Garden” (2006), was largely written while the author spent the summer of 2005 in Seattle and focuses on perennials and subshrubs. “Deer in My Garden: Volume 2” (2008) considers the impact on groundcovers and garden edge plants.