Hulda Klager (1863-1960) was a Pacific Northwest pioneer. This Woodland, Washington farm wife survived numerous hardships, but is best remembered for the wonderful collection of lilacs she hybridized and introduced in the first half of the 20th century, and the garden now open to the public that displays those lilacs. The historical novel “Where Lilacs Still Bloom” by Jane Kirkpatrick is largely an accurate biography, with only minor liberties taken to amalgamate some of the real life personalities in Klager’s life.

Hulda Klager (1863-1960) was a Pacific Northwest pioneer. This Woodland, Washington farm wife survived numerous hardships, but is best remembered for the wonderful collection of lilacs she hybridized and introduced in the first half of the 20th century, and the garden now open to the public that displays those lilacs. The historical novel “Where Lilacs Still Bloom” by Jane Kirkpatrick is largely an accurate biography, with only minor liberties taken to amalgamate some of the real life personalities in Klager’s life.

Excerpted from the Fall 2012 Arboretum Bulletin.

George Bingham is based in Olympia and had been engaged in bonsai for about nine years when “What I’ve Learned from Bonsai” was published in 2008. This very personal book shares his observation about both the art of bonsai and the life lessons he has gained while working with his plants and living with multiple sclerosis.

George Bingham is based in Olympia and had been engaged in bonsai for about nine years when “What I’ve Learned from Bonsai” was published in 2008. This very personal book shares his observation about both the art of bonsai and the life lessons he has gained while working with his plants and living with multiple sclerosis.

Excerpted from the Fall 2012 Arboretum Bulletin.

The grandparent of all gardening books for the Pacific Northwest and rest of the west remains the “Sunset Western Garden Book.” Now in its new, ninth edition, the proven encyclopedic formula, along with essays, extensive plant selection lists for specific needs, and the much valued Sunset climate zones (all updated) continue to make this a must on any western gardener’s shelf. The main addition since the last edition of 2007 is photographs in the encyclopedia–a nice update!

The grandparent of all gardening books for the Pacific Northwest and rest of the west remains the “Sunset Western Garden Book.” Now in its new, ninth edition, the proven encyclopedic formula, along with essays, extensive plant selection lists for specific needs, and the much valued Sunset climate zones (all updated) continue to make this a must on any western gardener’s shelf. The main addition since the last edition of 2007 is photographs in the encyclopedia–a nice update!

Excerpted from the Fall 2012 Arboretum Bulletin.

Consider “The Intimate Garden” for very detailed examples of highly individualized garden spaces, with an emphasis on hardscape and ornaments. While both author Brian Coleman and photographer William Wright are from Seattle and the gardens are mostly on the west coast, examples from the east coast and even England are included, making this a very diverse selection of design styles and plant material.

Consider “The Intimate Garden” for very detailed examples of highly individualized garden spaces, with an emphasis on hardscape and ornaments. While both author Brian Coleman and photographer William Wright are from Seattle and the gardens are mostly on the west coast, examples from the east coast and even England are included, making this a very diverse selection of design styles and plant material.

Excerpted from the Fall 2012 Arboretum Bulletin.

Valerie Easton’s “Petal & Twig”, tells how to find a source of material for flower arranging in your own garden. If–like me–you’ve ever struggled with getting your home arrangements just right, Easton will loosen you up and give you permission to just go for it, and open your eyes to more possibilities than you ever imagined a few feet from your back door. “After all, you’re crafting performance art that changes hour by hour, day by day, as buds open, petals drop, and flowers droop. Imperfection engages us in the creative process.”

Valerie Easton’s “Petal & Twig”, tells how to find a source of material for flower arranging in your own garden. If–like me–you’ve ever struggled with getting your home arrangements just right, Easton will loosen you up and give you permission to just go for it, and open your eyes to more possibilities than you ever imagined a few feet from your back door. “After all, you’re crafting performance art that changes hour by hour, day by day, as buds open, petals drop, and flowers droop. Imperfection engages us in the creative process.”

Excerpted from the Fall 2012 Arboretum Bulletin.

“When Debra and David began interviewing and photographing people who grow and arrange fresh, seasonal flowers for local markets, I knew they were documenting a new movement…you could call it the slow flower movement.” This quote, by Amy Stewart from the Foreword of “The 50 Mile Bouquet,” well summarizes this forward-looking book by Debra Prinzing and David Perry, which leaves you with a wider perspective and appreciation of fresh cut flowers and other greenery. This is in sharp contrast to the international florist industry, making Stewart’s 2007 book about that industry, “Flower Confidential,” a good companion reading (Stewart–who lives in Eureka, California–almost qualifies as a local author).

“When Debra and David began interviewing and photographing people who grow and arrange fresh, seasonal flowers for local markets, I knew they were documenting a new movement…you could call it the slow flower movement.” This quote, by Amy Stewart from the Foreword of “The 50 Mile Bouquet,” well summarizes this forward-looking book by Debra Prinzing and David Perry, which leaves you with a wider perspective and appreciation of fresh cut flowers and other greenery. This is in sharp contrast to the international florist industry, making Stewart’s 2007 book about that industry, “Flower Confidential,” a good companion reading (Stewart–who lives in Eureka, California–almost qualifies as a local author).

Excerpted from the Fall 2012 Arboretum Bulletin.

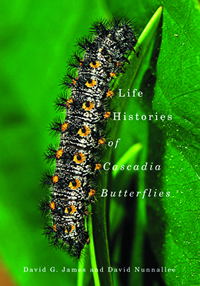

When first picking up the fascinating Life Histories of Cascadia Butterflies, I expected lots of lovely close-up photographs of our native butterflies. While I wasn’t disappointed, the majority of the photos are of the early stages of their life histories, i.e., lots of caterpillars! The thoroughness for depicting each species is outstanding with typically five or more photos of the different larval stages. How did authors David James and David Nunnallee do it? By rearing the butterflies from eggs and photographing each stage of their development.

When first picking up the fascinating Life Histories of Cascadia Butterflies, I expected lots of lovely close-up photographs of our native butterflies. While I wasn’t disappointed, the majority of the photos are of the early stages of their life histories, i.e., lots of caterpillars! The thoroughness for depicting each species is outstanding with typically five or more photos of the different larval stages. How did authors David James and David Nunnallee do it? By rearing the butterflies from eggs and photographing each stage of their development.

Robert Michael Pyle wrote the Foreword and he best describes the enormous scale of this work: “…this book is the apex of life history treatments to date. In the whole world, no other comparable region enjoys a work of this scale, ambit, and acuity for its butterfly fauna”.

Excerpted from the Fall 2012 Arboretum Bulletin.

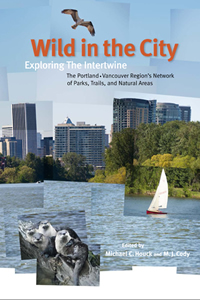

Wild in the City is an invaluable guide for an exploration of the parks and trails in the Portland metropolitan area, but it’s quite readable even if you’re stuck somewhere else. Scattered amongst the trail maps and descriptions of various sites and walks are essays about wildlife, history–both natural and human–and the complexities of disturbed ecosystems, with a good dose of philosophy on the value of having nature in an urban setting. Over one hundred writers and illustrators have contributed to this fine work.

Wild in the City is an invaluable guide for an exploration of the parks and trails in the Portland metropolitan area, but it’s quite readable even if you’re stuck somewhere else. Scattered amongst the trail maps and descriptions of various sites and walks are essays about wildlife, history–both natural and human–and the complexities of disturbed ecosystems, with a good dose of philosophy on the value of having nature in an urban setting. Over one hundred writers and illustrators have contributed to this fine work.

Excerpted from the Fall 2012 Arboretum Bulletin.

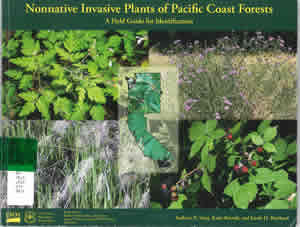

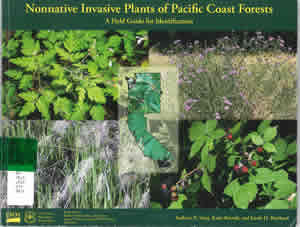

Nonnative Invasive Plants of Pacific Coast Forests is an unusual field guide that helps to identify plants you don’t want to find–but you probably will–especially in the forests of Washington, Oregon, and California. In various ways, these plants are negatively affecting our native plants, animals, and ecosystems. The intent of the authors is to make these recognizable to a larger audience beyond highly trained botanists. Many selections, such as purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria) and herb-robert (Geranium robertianum), are all too familiar to gardeners and visitors to the Arboretum. Others will be less familiar, or you might not know they are a problem, such as some of our popular cotoneasters (Cotoneaster franchetii and C. lacteus).

Nonnative Invasive Plants of Pacific Coast Forests is an unusual field guide that helps to identify plants you don’t want to find–but you probably will–especially in the forests of Washington, Oregon, and California. In various ways, these plants are negatively affecting our native plants, animals, and ecosystems. The intent of the authors is to make these recognizable to a larger audience beyond highly trained botanists. Many selections, such as purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria) and herb-robert (Geranium robertianum), are all too familiar to gardeners and visitors to the Arboretum. Others will be less familiar, or you might not know they are a problem, such as some of our popular cotoneasters (Cotoneaster franchetii and C. lacteus).

Excerpted from the Fall 2012 Arboretum Bulletin.

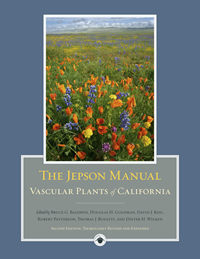

Many of the over 7,000 vascular plant species of California described in The Jepson Manual can also be found in the Pacific Northwest.

Many of the over 7,000 vascular plant species of California described in The Jepson Manual can also be found in the Pacific Northwest.

The name perhaps needs clarification. Willis Linn Jepson was an early 20th century botanist who published several books on California flora, including the first that was both comprehensive and statewide for vascular plants (“A Manual of the Flowering Plants of California”–1925). The 1993 first edition of “The Jepson Manual” honored his memory, and this new edition continues that honor while incorporating new discoveries and the many changes in botanical systematics of the last twenty years.

Excerpted from the Fall 2012 Arboretum Bulletin.

Hulda Klager (1863-1960) was a Pacific Northwest pioneer. This Woodland, Washington farm wife survived numerous hardships, but is best remembered for the wonderful collection of lilacs she hybridized and introduced in the first half of the 20th century, and the garden now open to the public that displays those lilacs. The historical novel “Where Lilacs Still Bloom” by Jane Kirkpatrick is largely an accurate biography, with only minor liberties taken to amalgamate some of the real life personalities in Klager’s life.

Hulda Klager (1863-1960) was a Pacific Northwest pioneer. This Woodland, Washington farm wife survived numerous hardships, but is best remembered for the wonderful collection of lilacs she hybridized and introduced in the first half of the 20th century, and the garden now open to the public that displays those lilacs. The historical novel “Where Lilacs Still Bloom” by Jane Kirkpatrick is largely an accurate biography, with only minor liberties taken to amalgamate some of the real life personalities in Klager’s life. George Bingham is based in Olympia and had been engaged in bonsai for about nine years when “What I’ve Learned from Bonsai” was published in 2008. This very personal book shares his observation about both the art of bonsai and the life lessons he has gained while working with his plants and living with multiple sclerosis.

George Bingham is based in Olympia and had been engaged in bonsai for about nine years when “What I’ve Learned from Bonsai” was published in 2008. This very personal book shares his observation about both the art of bonsai and the life lessons he has gained while working with his plants and living with multiple sclerosis. The grandparent of all gardening books for the Pacific Northwest and rest of the west remains the “Sunset Western Garden Book.” Now in its new, ninth edition, the proven encyclopedic formula, along with essays, extensive plant selection lists for specific needs, and the much valued Sunset climate zones (all updated) continue to make this a must on any western gardener’s shelf. The main addition since the last edition of 2007 is photographs in the encyclopedia–a nice update!

The grandparent of all gardening books for the Pacific Northwest and rest of the west remains the “Sunset Western Garden Book.” Now in its new, ninth edition, the proven encyclopedic formula, along with essays, extensive plant selection lists for specific needs, and the much valued Sunset climate zones (all updated) continue to make this a must on any western gardener’s shelf. The main addition since the last edition of 2007 is photographs in the encyclopedia–a nice update! Consider “The Intimate Garden” for very detailed examples of highly individualized garden spaces, with an emphasis on hardscape and ornaments. While both author Brian Coleman and photographer William Wright are from Seattle and the gardens are mostly on the west coast, examples from the east coast and even England are included, making this a very diverse selection of design styles and plant material.

Consider “The Intimate Garden” for very detailed examples of highly individualized garden spaces, with an emphasis on hardscape and ornaments. While both author Brian Coleman and photographer William Wright are from Seattle and the gardens are mostly on the west coast, examples from the east coast and even England are included, making this a very diverse selection of design styles and plant material. Valerie Easton’s “Petal & Twig”, tells how to find a source of material for flower arranging in your own garden. If–like me–you’ve ever struggled with getting your home arrangements just right, Easton will loosen you up and give you permission to just go for it, and open your eyes to more possibilities than you ever imagined a few feet from your back door. “After all, you’re crafting performance art that changes hour by hour, day by day, as buds open, petals drop, and flowers droop. Imperfection engages us in the creative process.”

Valerie Easton’s “Petal & Twig”, tells how to find a source of material for flower arranging in your own garden. If–like me–you’ve ever struggled with getting your home arrangements just right, Easton will loosen you up and give you permission to just go for it, and open your eyes to more possibilities than you ever imagined a few feet from your back door. “After all, you’re crafting performance art that changes hour by hour, day by day, as buds open, petals drop, and flowers droop. Imperfection engages us in the creative process.” “When Debra and David began interviewing and photographing people who grow and arrange fresh, seasonal flowers for local markets, I knew they were documenting a new movement…you could call it the slow flower movement.” This quote, by Amy Stewart from the Foreword of “The 50 Mile Bouquet,” well summarizes this forward-looking book by Debra Prinzing and David Perry, which leaves you with a wider perspective and appreciation of fresh cut flowers and other greenery. This is in sharp contrast to the international florist industry, making Stewart’s 2007 book about that industry, “Flower Confidential,” a good companion reading (Stewart–who lives in Eureka, California–almost qualifies as a local author).

“When Debra and David began interviewing and photographing people who grow and arrange fresh, seasonal flowers for local markets, I knew they were documenting a new movement…you could call it the slow flower movement.” This quote, by Amy Stewart from the Foreword of “The 50 Mile Bouquet,” well summarizes this forward-looking book by Debra Prinzing and David Perry, which leaves you with a wider perspective and appreciation of fresh cut flowers and other greenery. This is in sharp contrast to the international florist industry, making Stewart’s 2007 book about that industry, “Flower Confidential,” a good companion reading (Stewart–who lives in Eureka, California–almost qualifies as a local author). When first picking up the fascinating Life Histories of Cascadia Butterflies, I expected lots of lovely close-up photographs of our native butterflies. While I wasn’t disappointed, the majority of the photos are of the early stages of their life histories, i.e., lots of caterpillars! The thoroughness for depicting each species is outstanding with typically five or more photos of the different larval stages. How did authors David James and David Nunnallee do it? By rearing the butterflies from eggs and photographing each stage of their development.

When first picking up the fascinating Life Histories of Cascadia Butterflies, I expected lots of lovely close-up photographs of our native butterflies. While I wasn’t disappointed, the majority of the photos are of the early stages of their life histories, i.e., lots of caterpillars! The thoroughness for depicting each species is outstanding with typically five or more photos of the different larval stages. How did authors David James and David Nunnallee do it? By rearing the butterflies from eggs and photographing each stage of their development. Wild in the City is an invaluable guide for an exploration of the parks and trails in the Portland metropolitan area, but it’s quite readable even if you’re stuck somewhere else. Scattered amongst the trail maps and descriptions of various sites and walks are essays about wildlife, history–both natural and human–and the complexities of disturbed ecosystems, with a good dose of philosophy on the value of having nature in an urban setting. Over one hundred writers and illustrators have contributed to this fine work.

Wild in the City is an invaluable guide for an exploration of the parks and trails in the Portland metropolitan area, but it’s quite readable even if you’re stuck somewhere else. Scattered amongst the trail maps and descriptions of various sites and walks are essays about wildlife, history–both natural and human–and the complexities of disturbed ecosystems, with a good dose of philosophy on the value of having nature in an urban setting. Over one hundred writers and illustrators have contributed to this fine work. Nonnative Invasive Plants of Pacific Coast Forests is an unusual field guide that helps to identify plants you don’t want to find–but you probably will–especially in the forests of Washington, Oregon, and California. In various ways, these plants are negatively affecting our native plants, animals, and ecosystems. The intent of the authors is to make these recognizable to a larger audience beyond highly trained botanists. Many selections, such as purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria) and herb-robert (Geranium robertianum), are all too familiar to gardeners and visitors to the Arboretum. Others will be less familiar, or you might not know they are a problem, such as some of our popular cotoneasters (Cotoneaster franchetii and C. lacteus).

Nonnative Invasive Plants of Pacific Coast Forests is an unusual field guide that helps to identify plants you don’t want to find–but you probably will–especially in the forests of Washington, Oregon, and California. In various ways, these plants are negatively affecting our native plants, animals, and ecosystems. The intent of the authors is to make these recognizable to a larger audience beyond highly trained botanists. Many selections, such as purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria) and herb-robert (Geranium robertianum), are all too familiar to gardeners and visitors to the Arboretum. Others will be less familiar, or you might not know they are a problem, such as some of our popular cotoneasters (Cotoneaster franchetii and C. lacteus). Many of the over 7,000 vascular plant species of California described in The Jepson Manual can also be found in the Pacific Northwest.

Many of the over 7,000 vascular plant species of California described in The Jepson Manual can also be found in the Pacific Northwest.