We’ve bought some butternut squash starts, and from what I’ve read online,

they require a lot of space. This will be my first time growing them. We

have 4′ x 6′ x 1′ raised beds, and I’m wondering if one bed will be big enough to plant 1 butternut squash start. Also, I’ve read that they require staking?

Is this true? What should we do with the other 2 starts that we got if we don’t have room for them in our raised beds? Try planting them directly into

the ground? I’d hate to throw them out…

We also bought a raspberry plant, and I’ve read that they should have 14-18″

for their roots. Again, our raised beds are only 1 foot deep. Would we be

better off digging a hole in the ground?

There is conflicting information in different sources about the amount of space butternut squash needs. Most sources say (as Seattle Tilth’s Maritime Northwest Garden Guide does) the gardener should allow 18-24 inches between plants, which would mean you could plant all 6 starts in one 4′ by 6′ raised bed. Steve Solomon, however, says in Growing Vegetables West of the Cascades that winter squashes require much more space, so that you could only plant two in your 4′ by 6′ bed.

Staking winter squash can be done to save space. There is a pretty good description of how to do it in Mel Bartholomew’s book, Square Foot Gardening. Basically, the vines are planted 4 feet apart in a trench prepared with “large-mesh wire fencing” on 6-foot posts, and twined through the fencing as they grow. He says the stems are strong enough to support the heavy squashes. The technique is also mentioned in Vegetables, Herbs & Fruit: An Illustrated Encyclopedia by Matthew Biggs, Jekka McVicar, and Bob Flowerdew.

As for your raspberry, it will grow faster and better with deep, rich soil. However, raspberries have a tendency to spread by underground runners, so it is often a good idea to contain them in some way. Depending on what is under your raised beds (i.e., soil, sand, concrete) you may wish to plant them there despite the shallow depth, or dig/mound up within the raised bed to improve the soil depth, or plant the raspberry elsewhere.

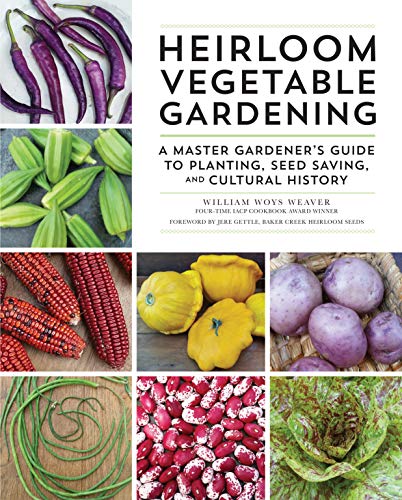

The book “Heirloom Vegetable Gardening” was a classic almost from the moment it was first published in 1997. The author, William Woys Weaver, is a rare scholar of the kitchen garden with a PhD in food ethnography, or the study of cultural eating habits.

The book “Heirloom Vegetable Gardening” was a classic almost from the moment it was first published in 1997. The author, William Woys Weaver, is a rare scholar of the kitchen garden with a PhD in food ethnography, or the study of cultural eating habits.