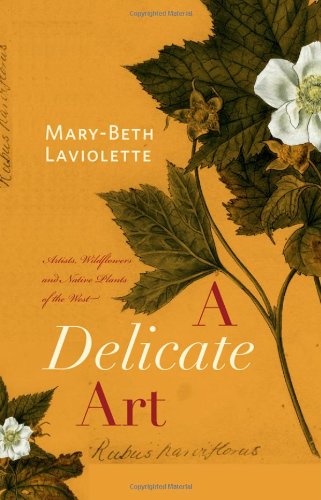

In the late 19th century in western Canada there were two women who, while not sisters, had a lot in common. Much of their stories are found in “A Delicate Art: Artists, Wildflowers and Native Plants of the West” by Mary-Beth Laviolette.

In the late 19th century in western Canada there were two women who, while not sisters, had a lot in common. Much of their stories are found in “A Delicate Art: Artists, Wildflowers and Native Plants of the West” by Mary-Beth Laviolette.

Mary Schäffer Warren (1861-1939) and Mary Vaux Walcott (1860-1940) were both of Quaker families living in Philadelphia, arguably the center for science and culture in America at the time. They both developed strong interests in the natural world, and developed the skills to paint in watercolors the native plants they found.

They joined a trip of the Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences to the Rockies and Selkirk Mountains of eastern British Columbia and western Alberta in 1889, traveling together part of the way on the top of a box car! They brought this same adventuresome passion to hiking and exploring the peaks, returning every summer for many years.

The pathways of the two Marys eventually diverged. Mary Vaux Walcott continued visiting the region every summer, but typically in the company of her two brothers, who were interested in studying the glaciers. As the only daughter, at age 20 she was expected to look after her father and brothers after the death of her mother. As Laviolette writes, the three siblings had “many summers spent in the western alpine, and for Mary in particular a lifelong commitment of over forty years in the area. To come were the pleasures of mountain rambling and backcountry camping in addition to the study of wildflowers and, on an entirely different scale, glaciers.”

Walcott finally broke this pattern by getting married at age 54 to Charles Doolittle Walcott, who she met in the mountains, and who was the head of the Smithsonian Institution. Together, they intensified their study of native plants, resulting in the publication of the five-volume “North American Wild Flowers” from 1925-1929. The Miller Library has only volume five of this set, with 76 of the 400 original prints, but all are reproduced in the 1953 publication “Wild Flowers of America” and most are part of a splendid new (2022) collection by Pamela Henson, “Wild Flowers of North America.” These later publications are both in the library’s general collection.

While titles suggest a comprehensive collection of the native, flowering plants of the United States and Canada, the emphasis is on the places where the Walcotts’ explored. The Canadian mountains and foothills fill in for much of western America, including our state, while the other emphasis is the Atlantic seaboard. The southwest species are mostly missing, but these are still impressive works.

Excerpted from Brian Thompson’s article in the Winter 2022 issue of the Arboretum Bulletin, updated June 2023

Winter is a great time to read the classics of horticultural literature. Gardeners from decades or even centuries ago still have many lessons to share with us. One I recommend is “The Wild Garden” by William Robinson (1838-1935).

Winter is a great time to read the classics of horticultural literature. Gardeners from decades or even centuries ago still have many lessons to share with us. One I recommend is “The Wild Garden” by William Robinson (1838-1935).

In the late 19th century in western Canada there were two women who, while not sisters, had a lot in common. Much of their stories are found in “A Delicate Art: Artists, Wildflowers and Native Plants of the West” by Mary-Beth Laviolette.

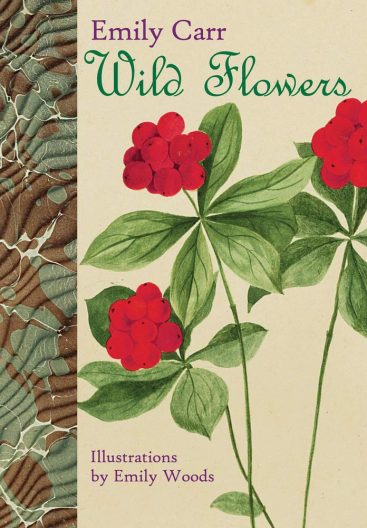

In the late 19th century in western Canada there were two women who, while not sisters, had a lot in common. Much of their stories are found in “A Delicate Art: Artists, Wildflowers and Native Plants of the West” by Mary-Beth Laviolette. Emily Carr (1871-1945) was a native of Victoria, British Columbia and lived much of her life in that city. She is best known as a painter, but was also an accomplished writer. Many of her works in both disciplines reflected her passionate interest in the indigenous peoples of Vancouver Island and other parts of British Columbia.

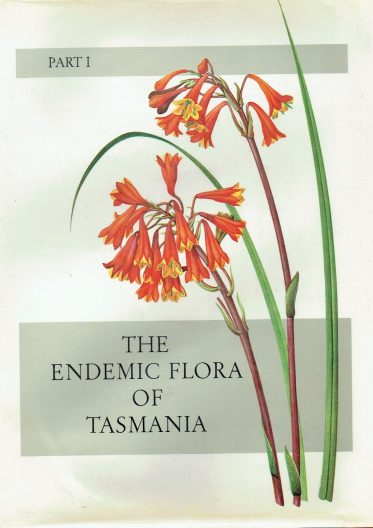

Emily Carr (1871-1945) was a native of Victoria, British Columbia and lived much of her life in that city. She is best known as a painter, but was also an accomplished writer. Many of her works in both disciplines reflected her passionate interest in the indigenous peoples of Vancouver Island and other parts of British Columbia. “I am glad that the month of October 1970 has been assigned to us for displaying the original artwork for The Endemic Flora of Tasmania.” This is the beginning of a letter written in December 1969 to Brian O. Mulligan, the Director of what was known then as the University of Washington Arboretum. The writer was Robert D. Monroe, the Chief of Special Collections Division of the University Library (now University Libraries) which would host the exhibit in the Smith Room of Suzzallo Library.

“I am glad that the month of October 1970 has been assigned to us for displaying the original artwork for The Endemic Flora of Tasmania.” This is the beginning of a letter written in December 1969 to Brian O. Mulligan, the Director of what was known then as the University of Washington Arboretum. The writer was Robert D. Monroe, the Chief of Special Collections Division of the University Library (now University Libraries) which would host the exhibit in the Smith Room of Suzzallo Library.