Catharine Parr Traill (1802-1899) and Susanna Moodie (1803-1885) were sisters who immigrated to Canada from England in 1832. Both newly married, they were part of a movement of settlers from Britain seeking to escape poverty by moving to Upper Canada (now the province of Ontario), where they hoped to establish a prosperous new home.

Catharine Parr Traill (1802-1899) and Susanna Moodie (1803-1885) were sisters who immigrated to Canada from England in 1832. Both newly married, they were part of a movement of settlers from Britain seeking to escape poverty by moving to Upper Canada (now the province of Ontario), where they hoped to establish a prosperous new home.

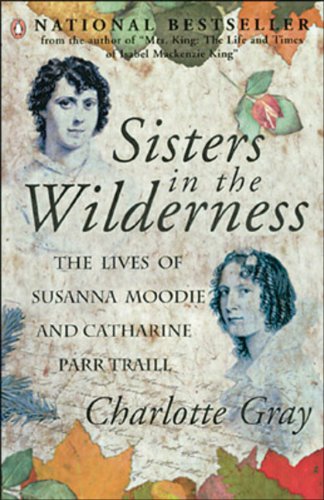

The reality was quite different. Although they settled within 50 miles of each other, the harshness of travel and limited communications prevented them from visiting each other for two years. “Sisters in the Wilderness” is a biography by Charlotte Gray about the two sisters who both eventually thrived as authors in their new home, despite a bleak beginning.

The sisters had a relatively good start in life. Gray described their household of six sisters and two brothers – all who lived long lives – as rich in books and creativity. The family was related to Sir Isaac Newton and inherited much of his library. But the father died young, and the family was left with limited resources. Out of this experience, six of the siblings became published authors, a very unusual success rate spurred by necessity.

The two Canadian sisters were especially prolific. Susanna Moodie is best known for “Roughing it in the Bush,” her 1852 book about her early years in North America. Her work was the inspiration for modern Canadian writer, Margaret Atwood, in her 1970 book of poetry, “The Journals of Susanna Moodie.”

However, the focus of this review is on Catharine Parr Traill. Named after the surviving, last wife of King Henry VIII of England (and a distant relation), she was a survivor herself, living to 97 and achieving a great deal of fame in her later life, primarily for her books about the wildflowers of Canada. She was an avid field botanist and “took a serious interest in every aspect of a plant: its appearance, its life cycle, its medicinal and food value, its relation to other plants.” She also recognized that the wild country in which she struggled to survive was beginning to disappear, and along with it many of the native plants.

To help with her research, she acquired a small library of books intended for professional botanists. However, her goal was to publish a book for a more general audience. She began by writing articles for both Canadian and American popular magazines.

Traill was an excellent observer and writing, but she lacked the artistic skills to illustrate the book she hoped to publish. By the 1860s, her sister’s children had grown up and one of them, Agnes Moodie Fitzgibbon (1833-1913), was an accomplished painter. Fitzgibbon also became a tireless promoter of her aunt’s book, signing up many buyers before the book was printed. A young widow, she drew ten illustrations for the book and printed 500 copies of each. She then engaged her three daughters, ages 16, 13, and 10, at their dining room table to hand color every one – a total of 5,000 illustrations!

“Canadian Wild Flowers” was published in 1868. The timing was excellent, as it was just a year after Canadian independence. Traill writes in the Preface: “With a patriotic pride in her native land, Mrs. F. [Agnes Moodie Fitzgibbon] was desirous that the book should be entirely of Canadian production, without any foreign aid, and thus far her design has been carried out; whether successfully or not, remains for the public to decide.” This gamble was very successful as the book was indeed a popular expression of national pride. The Miller Library has a facsimile of this book.

Traill’s contribution to this first book was in the form of narrative descriptions of the plants in the illustrations. As this only totaled 30 species, the botanical information is limited, but the sumptuous illustrations ensured the book’s popularity.

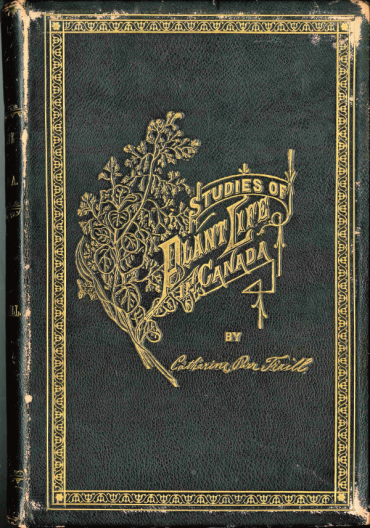

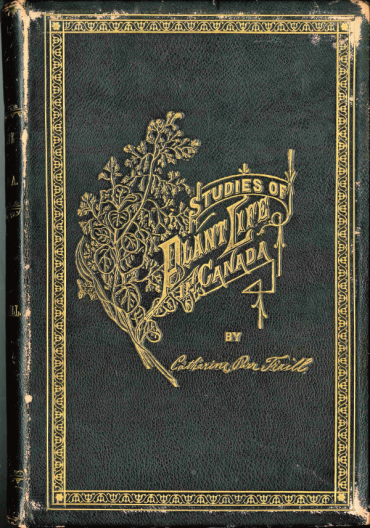

Traill’s second wild flower book, “Studies of Plant Life in Canada,” was published in 1885 with the rich details of author’s significant knowledge of the native plants where she had now lived for over 50 years, roughly 100 miles northeast of Toronto. Once again, her niece (now remarried and credited as Mrs. Chamberlain) provided the illustrations, but these are smaller and were printed using chromolithography, a relatively new process that eliminated the need for hand coloring. Instead, the focus of this later book (in the Miller Library collection) is on the text with descriptions of over 400 species, including trees, shrubs, and ferns.

Excerpted from the Winter 2022 issue of the Arboretum Bulletin

After moving from a lifetime in New York City to the flatlands of central Illinois, my friend Cecile decided to buy landscapes painted by local artists to teach the family how to look at the land around them that seemed oppressively monotonous. That was my introduction to the idea of seeing landscapes from different perspectives. Landskipping shows the reader two ways of looking at rural Britain that emerged in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Along the way, the book describes many engaging places.

After moving from a lifetime in New York City to the flatlands of central Illinois, my friend Cecile decided to buy landscapes painted by local artists to teach the family how to look at the land around them that seemed oppressively monotonous. That was my introduction to the idea of seeing landscapes from different perspectives. Landskipping shows the reader two ways of looking at rural Britain that emerged in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Along the way, the book describes many engaging places. In the late 19th century in western Canada there were two women who had a lot in common. Mary Schäffer Warren (1861-1939) and Mary Vaux Walcott (1860-1940) were both of Quaker families living in Philadelphia, arguably the center for science and culture in America at the time. They both developed strong interests in the natural world, and developed the skills to paint in watercolors the native plants they found.

In the late 19th century in western Canada there were two women who had a lot in common. Mary Schäffer Warren (1861-1939) and Mary Vaux Walcott (1860-1940) were both of Quaker families living in Philadelphia, arguably the center for science and culture in America at the time. They both developed strong interests in the natural world, and developed the skills to paint in watercolors the native plants they found. Catharine Parr Traill (1802-1899) and Susanna Moodie (1803-1885) were sisters who immigrated to Canada from England in 1832. Both newly married, they were part of a movement of settlers from Britain seeking to escape poverty by moving to Upper Canada (now the province of Ontario), where they hoped to establish a prosperous new home.

Catharine Parr Traill (1802-1899) and Susanna Moodie (1803-1885) were sisters who immigrated to Canada from England in 1832. Both newly married, they were part of a movement of settlers from Britain seeking to escape poverty by moving to Upper Canada (now the province of Ontario), where they hoped to establish a prosperous new home. Catharine Parr Traill (1802-1899) and Susanna Moodie (1803-1885) were sisters who immigrated to Canada from England in 1832. Both newly married, they were part of a movement of settlers from Britain seeking to escape poverty by moving to Upper Canada (now the province of Ontario), where they hoped to establish a prosperous new home.

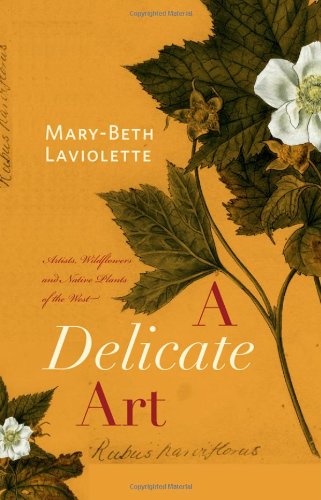

Catharine Parr Traill (1802-1899) and Susanna Moodie (1803-1885) were sisters who immigrated to Canada from England in 1832. Both newly married, they were part of a movement of settlers from Britain seeking to escape poverty by moving to Upper Canada (now the province of Ontario), where they hoped to establish a prosperous new home. In the late 19th century in western Canada there were two women who, while not sisters, had a lot in common. Much of their stories are found in “A Delicate Art: Artists, Wildflowers and Native Plants of the West” by Mary-Beth Laviolette.

In the late 19th century in western Canada there were two women who, while not sisters, had a lot in common. Much of their stories are found in “A Delicate Art: Artists, Wildflowers and Native Plants of the West” by Mary-Beth Laviolette.