Brewster Rogerson (1921-2015) spent most of his academic career teaching English at Kansas State University. The purchase of four clematis plants began the focus of the latter part of his life, leading after retirement to his move to Oregon for a climate more conducive to his favorite genus.

Brewster Rogerson (1921-2015) spent most of his academic career teaching English at Kansas State University. The purchase of four clematis plants began the focus of the latter part of his life, leading after retirement to his move to Oregon for a climate more conducive to his favorite genus.

His efforts to develop a comprehensive collection is recounted in “A Passion for Clematis” by the Friends of the Rogerson Clematis Collection. Now grown at the Luscher Farm, owned by the City of Lake Oswego, Oregon, this assemblage is one of the newer horticultural treasures to visit in the Pacific Northwest.

The garden is divided into many sections, all highlighted in this short book. These include heirlooms more than hundred years old, species and cultivars from different regions of the world, and Rogerson’s favorite selections. If one is overwhelmed by these choices, a beginner’s garden demonstrates several easy, widely available selections.

Rogerson’s comments in a letter to another avid collector will resonate with many gardeners: “Being no botanist by training, and only a rather clumsy gardener, I find I need to pick up everything I can from every clematis grower, big or little, I can find, and so far I’ve done pretty well.”

Excerpted from the Fall 2021 issue of the Arboretum Bulletin

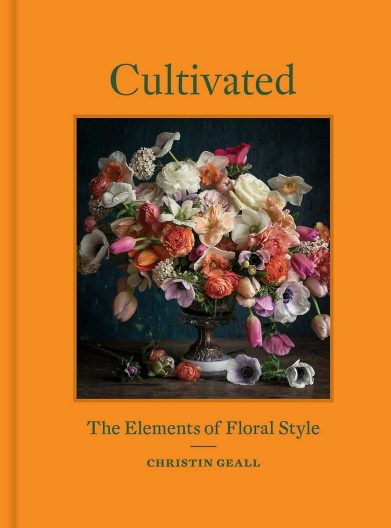

One tool that librarians use to organize books is the subject headings in catalog entries. For “Cultivated: The Elements of Floral Style,” the single subject heading term as provided by the Library of Congress is “flower arrangement.” While this choice is technically correct, this new book by Victoria, BC author and photographer Christin Geall is also a memoir, and explores deeper matters than most books with the same heading.

One tool that librarians use to organize books is the subject headings in catalog entries. For “Cultivated: The Elements of Floral Style,” the single subject heading term as provided by the Library of Congress is “flower arrangement.” While this choice is technically correct, this new book by Victoria, BC author and photographer Christin Geall is also a memoir, and explores deeper matters than most books with the same heading. For 15 years, the Elisabeth C. Miller Library has been hosting an exhibit by the Pacific Northwest Botanical Artists every spring. These artists keep alive a tradition of many centuries by creating scientifically accurate portrayals of the flowers, leaves, seeds, and other parts of plants, often with more detail and accuracy than a photograph.

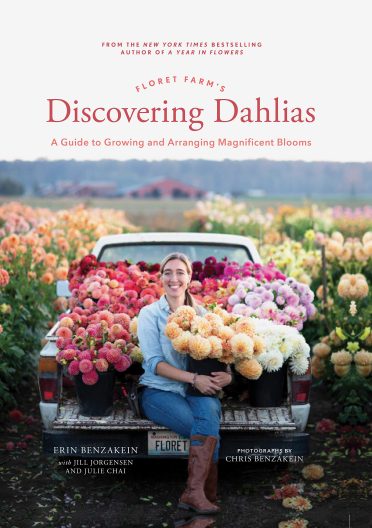

For 15 years, the Elisabeth C. Miller Library has been hosting an exhibit by the Pacific Northwest Botanical Artists every spring. These artists keep alive a tradition of many centuries by creating scientifically accurate portrayals of the flowers, leaves, seeds, and other parts of plants, often with more detail and accuracy than a photograph. We have several books on dahlias in the Miller Library collection, but none provide as much photographic detail on the different forms and the methods of growing, especially the harvesting, storing, and dividing of dahlia tubers as “Floret Farm’s Discovering Dahlias.” This how-to section also has a demonstration of hybridizing and creating your own dahlia varieties.

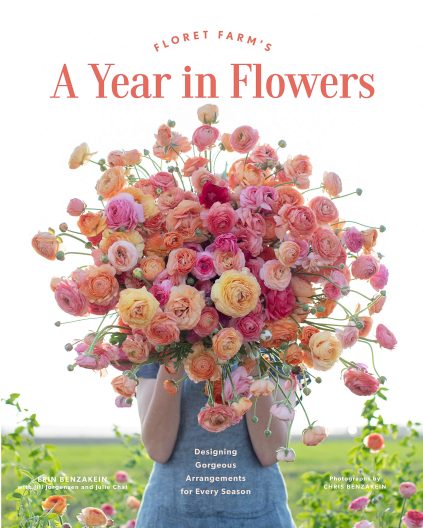

We have several books on dahlias in the Miller Library collection, but none provide as much photographic detail on the different forms and the methods of growing, especially the harvesting, storing, and dividing of dahlia tubers as “Floret Farm’s Discovering Dahlias.” This how-to section also has a demonstration of hybridizing and creating your own dahlia varieties. “Floret Farm’s A Year in Flowers”, is an especially helpful book on flower arranging for those who prefer a structured teaching approach and lots of practical matters, along with inspiration. To do this, Erin Benzakein and her co-authors use many comparison photographs.

“Floret Farm’s A Year in Flowers”, is an especially helpful book on flower arranging for those who prefer a structured teaching approach and lots of practical matters, along with inspiration. To do this, Erin Benzakein and her co-authors use many comparison photographs. John Albers has highlighted his garden of 20 years in Bremerton and his passion for sustainable gardening practices in two previous books. Now, he turns his attention to a favorite plant group: conifers, especially dwarf and small cultivars. He is very clear in his reasons for writing the book. “Given the horticultural and ecological importance of urban conifers, it is vital that all of us do our part to restore conifers to our urban environment.”

John Albers has highlighted his garden of 20 years in Bremerton and his passion for sustainable gardening practices in two previous books. Now, he turns his attention to a favorite plant group: conifers, especially dwarf and small cultivars. He is very clear in his reasons for writing the book. “Given the horticultural and ecological importance of urban conifers, it is vital that all of us do our part to restore conifers to our urban environment.” “Japanese Gardening: A Practical Guide” provides a long-needed book on how to apply the principles of Japanese style gardens on a small scale, allowing the incorporation of Japanese garden elements in a home garden.

“Japanese Gardening: A Practical Guide” provides a long-needed book on how to apply the principles of Japanese style gardens on a small scale, allowing the incorporation of Japanese garden elements in a home garden.![[Around the World in 80 Plants] cover](https://depts.washington.edu/hortlib/graphix/aroundtheworldin80plants300.jpg)

![[book title] cover](https://depts.washington.edu/hortlib/graphix/theKinfolkgarden300.jpg)

![[Tokachi Millennium] cover](https://depts.washington.edu/hortlib/graphix/TokachiMilleniumForest300.jpg)