While other Washington State chapters may have had more members at their peak, probably the strongest and longest lasting Ku Klux Klan presence in the 1920s and 1930s was in Whatcom and Skagit Counties, organized in particular around the towns of Bellingham and Mount Vernon. While many Klan chapters faded in the late 1920s, according to one local resident, the chapters in these counties “never did disband.”1

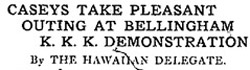

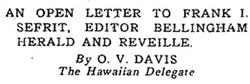

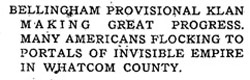

Little evidence of Klan activity in these counties exists prior to July 4, 1923, when local Klansmen burned a cross on the top of Sehome Hill in Bellingham and apparently got into a fist-fight with a few angry residents who went to confront them.2 Following that, a writer going by the name O.V. Davis, “The Hawaiian Delegate”, started offering regular reports of Klan activity in and around Bellingham in the state Klan’s newspaper, The Watcher on the Tower. The Bellingham group held an August 19 membership initiation ceremony at which sailors stationed aboard the U.S.S. Tennessee were made honored guests. It is likely that this meeting was attended by Klan organizers John J. Jeffrey, Luther I. Powell, and J. Arthur Herdon (to organize non-citizens) who were reported to have visited Bellingham in late August.3 Following it, Davis announced “our great membership drive this Fall” which likely established Bellingham’s chapter.

Other than some Klansmen handing $20 to a pastor at a Sunday service on October 22, 1923, most of the news coverage of the Klan in Whatcom county during 1924 focused on I-49, the anti-catholic school bill which was soundly defeated. But whereas most Klan chapters declined after that election, the Klan in Bellingham and Mount Vernon areas were strong enough to not only continue but draw large crowds at a series of public events that began with a meeting of over a thousand in Stanwood in 1924. And some believe that Marion A. Keyes, who was elected Mayor of Blaine in 1924, was a member of the Klan.

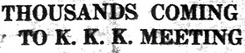

On September 26th, 1925, the “largest crowd that has ever assembled in the Lynden District,” estimated between 12,000 and 25,000 people, attended a rally of supposedly 750 members of the Ku Klux Klan at the Northwest Washington Fair Grounds.4 The vast majority of the 160 people initiated into the Klan that night were, according to the Bellingham Herald (which was a supporter of the Klan) “chiefly from Bellingham, Anacortes, Mount Vernon, Stanwood and Everett.”5 There was also reportedly “a large delegation from Canada.” The Vancouver, BC Klan held a large march a month later.6

The following year, the local Klan sought to capitalize upon its gains by incorporating itself into the Bellingham Tulip festival parade. The proposal was initially accepted by the Tulip festival planning committee, but controversy forced the committee to reconsider. To avert a crisis, the Klan decided to pull out of the Festival and stage its own mile-long parade of 762 local Klan members on May 15, 1926 through downtown Bellingham.7Immediately following a Klan picnic at Cornwall Park, the parade featured a statue of liberty riding a KKK float, the women’s Klan auxiliary, “Klavaliers” on horses, “three members of the original Klan” (from the 1860s) and other Klan members.8

Three years later, on July 27th and 28th, 1929, the Bellingham Klan chapter hosted the Washington State KKK annual convention, attended by delegates from dozens of Ku Klux Klan chapters. Bellingham Mayor John A. Kellogg addressed the convention while standing in front of an enormous electric cross, and concluded his remarks by presenting Grand Dragon EB Quackenbush from Spokane with the Key to the City. During his speech, Kellogg also acknowledged Bellingham City Attorney Charles B. Sampley, described by the Bellingham Herald as “a prominent Klansman” who the crowd “hailed as a conquering hero.”9

A decision to make the KKK less secretive was one of the highlights of 1929 convention. Only women wore robes at the two day meeting, but the conference concluded with a parade through downtown Bellingham with all wearing full Klan regalia.

As Gabriel Mayer wrote for the Journal of Whatcom County Historical Society, the decision to be less secret was a strange one given how open the Bellingham Klan was in the late 1920s. Its office in Rooms 212-213 of the Long Building was listed in the phone book, which also listed Klan meetings as happening every Tuesday night at Tulip Hall.

Less is known about what happened to the Whatcom and Skagit County Klan chapters in the 1930s. Though not all of them joined the pro-Hitler Silver Legion in the 1930s, much of the Silver Legion in those two Counties reportedly came from former Klan members.10

And in 1934, Blanton Lather, a high ranking Klan official, teamed up prominent local conservatives (including the editor of the Bellingham Herald, women from a group called “Pro-America”, and a former officer in the American Legion) to demand the resignation of Charles H. Fisher, the president of Western Washington State College in Bellingham. They accused President Fisher of inviting “members of subversive organizations, and of free love, atheistic, and un-American pacifist organizations” to speak on campus to the exclusion of “pro-Americans.” He was also charged with anti-Christian bias; lack of patriotism; and tolerating “anti-American” student groups.11

Though the school’s Board of Trustees found the allegations groundless, pressure continued for years. According to a historian of the College (now Western Washington University), “the fiery cross on Sehome Hill was a nocturnal spectacle in Bellingham at this time.”12 And on the diplomatic front, the ad-hoc committee began lobbying Governor Clarence Martin to fire Fisher. In 1937, Fisher’s contract expired though he continued to work without one. In October, 1938, Governor Martin convinced the school’s Board of Trustees to fire President Fisher after he refused to resign.13

The arc of the Ku Klux Klan in Whatcom County thus bridged a generation of conservative organizing. It began in the wake of the first Red Scare after World War I, and persisted in ways that foreshadowed the intimidation tactics and character assassination of the new anti-communism that emerged after World War II. In 1941, an American Association of University Professors report criticized Governor Martin for failing to protect academic freedom and for capitulating to the Klan and other supposedly patriotic groups when he had Fisher fired.14 But Martin’s actions were just the tip of the iceberg, and they showed how much influence a fringe group like the Klan could have. When State Legislator Albert Canwell launched an inquiry in 1948 based on the fanciful claim that 150 of the University of Washington’s 700 professors might be communists, he was following in the footsteps of Blanton Lather and creating a model for Joseph McCarthy’s Cold War hysteria at the same time.

Next: Ch5 –[](kkk_powell-ed.htm)The Ku Klux Klan and Vigilante Culture in Yakima Valley

“The Washington State Klan in the 1920s” by Trevor Griffey includes the following chapters:

- Citizen Klan: Electoral Politics and the KKK in WA

- Luther I. Powell, Northwest KKK Organizer

- The Ku Klux Klan in Seattle

- The Strongest Chapter in WA: Bellingham’s KKK

- The Ku Klux Klan and Vigilante Culture in Yakima Valley

- KKK Super Rallies in Washington State, 1923-24

- Social Klan: White Supremacy in Everyday Life

- The Washington State KKK and the U.S. Navy

- Non-Citizen Klan: Royal Riders of the Red Robe

Copyright (©) Trevor Griffey 2007

1 Donald Stuart Strong. Organized anti-Semitism in America: The Rise of Group Prejudice During the Decade 1930-40. Washington, D.C., American Council on Public Affairs, 1941. p. 50

2 The Hawaiian Delegate. “Caseys Take Pleasant Outing at Bellingham K.K.K. Demonstration” Watcher on the Tower. July 28, 1923, p.3

3 “Bellingham Provisional Klan Making Great Progress. Many Americans Flocking to Portals of Invisible Empire in Whatcom County.” Watcher on the Tower. Sept. 1, 1923, p.4

4 “Thousands Gather to Observe Klan: Largest Crowd in History of Lynden Witnesses Demosntration of Order at Fair Grounds.” Lynden Tribune. October 1, 1925, p1

5 Bellingham American, September 28, 1925, p3; “Open-Air Initiation of Klan at Lynden Is Seen by Large Crowd.” Bellingham Herald. Sept. 28, 1925, p2

6 “Thousands Gather to Observe Klan”

7 American Revielle. May 16, 1926 p 1

8 American Revielle., may 17 1926 p8

9 “Klansmen Convene and Will Stage Parade.” Bellingham Herald, July 27, 1929. p.1

10 Karen E. Hoppes. William Dudley Pelley and the Silvershirt Legion : a case study of the Legion in Washington State, 1933-1942. Unpublished PhD Dissertation, History, CUNY. p. 202

11 AAUP Bulletin, Feb 1941 p51

12 Meyer, p. 35

13 AAUP Bulletin, Feb 1941

14 ibid.