Even though it had the largest Ku Klux Klan Chapter in the state for a while, and its offices served as the headquarters for the Washington and Idaho Klan, not much is known about Seattle Klan No. 4 and other Klan chapters that succeeded it.

The Los Angeles Times reported in July of 1921 that the Klan had begun organizing in Washington State.1 But it was not until 1922 that King Kleagle Luther I. Powell founded Seattle Klan No. 4, which claimed a beginning membership of 2,000. The Seattle Klan’s office, which in addition to being a regional headquarters also served as the office of the Women’s Klan and the Royal Riders of the Red Robe, was located on the 6th floor of the Securities Building (1904 Third Avenue) in downtown Seattle.

While Powell exerted significant leadership over the Seattle Klan, its official leaders were Exalted Cyclops “Judge” John A. Jeffrey and Kligrapp William C. Ott. Jeffrey was a lawyer from Portland who seems to have first gotten involved with the Klan there. He was a featured speaker at many of the Klan’s largest events, and was also the head of a Klan front group called the Good Government League. He later served as a Klan leader in North Dakota, probably among a number of other places.2 It’s uncertain whether he was the same John A. Jeffrey who was elected to the Oregon State Legislature on the Populist People’s Party ticket in 1894.3

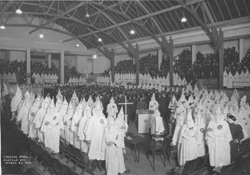

The Seattle Klan’s huge membership in 1923 meant that it had to move to ever larger meeting places, and also that its leaders started congregating in areas near their downtown office. The Palm Café nearby on Westlake Avenue became a regular hang-out for Klan members, and was nicknamed “The Klansmen’s Roost.”4 Klan chapter meetings were frequently held in three different places—Seattle’s Moose Hall, Swedish Hall (1629 8th Ave), and Carpenters Hall— that demonstrated the organization’s connection to fraternal orders, Scandinavian heritage, and conservative labor unions.5 A photo (above) of secret Klan meeting in March of 1923 was apparently taken at the Crystal Pool, at Second and Lenora, only a few blocks from the Seattle Klan’s office.6

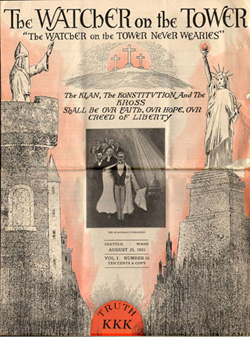

The Seattle Klan had little support from the city’s newspapers. Both the Seattle Times and the Seattle Post-Intelligencer saw the organization as dangerous, irrational, and unnecessary. Klan members replied in turn with defensive and disparaging remarks about the two Seattle papers in their own publication, the Watcher on the Tower.

The Seattle Klan had a turbulent history that, because it was a secret society, is difficult to document. Despite gaining thousands of members in the Spring and Summer of 1923, and sponsoring a massive rally that drew tens of thousands of people near Renton on July 14, 1923, the Seattle Klan was destabilized when Luther Powell left the city in the Fall of 1923, and its publication, the Watcher on the Tower, soon ceased publication. While the Seattle Klan was able to stage another rally of tens of thousands of people in Issaquah on July 26, 1924, it collapsed when its anti-Catholic school bill was badly defeated at the polls. “Even at its peak,” historian Kenneth Jackson argues, “Seattle Klan No. 4 never rivaled in power and influence the star klaverns of the West in Portland and Denver.”7

Following the Washington Klan’s electoral defeat in 1924, the national leader of the KKK, Imperial Wizard Hiram Evans, came to Seattle as part of a national tour. Historians of the KKK offer very different accounts of this visit. David Chalmers, using Evans’s propaganda as his source, wrote that Evans experienced

…triumphal receptions in Spokane, Seattle and Tacoma… He was regally treated in Washington as befitted the head of a far-flung fraternal Empire. He banqueted with the Scottish Rite Masons in Spokane, Seattle, and Tacoma, spoke in Moose Temples, and was feted by Seattle’s Chamber of Commerce. The only sour note, his national weekly commented, was the solitary opposition of William Randolph Hearst’s Seattle Post-Intelligencer.8

But, noted Kenneth Jackson, during that same visit, eight leading officers in the Seattle Klan, complaining that they were being bled dry of money by the national Klan, summarily resigned and formed their own split-off group. “Ignoring an attempt by Imperial Wizard Evans to shift local attention to motherhood and the Catholic Church, hundreds of Seattle Klansmen met in Carpenter’s Hall on November 17, 1924, and formed officially the International Klan of America.”9 Little is known about this organization or how long it lasted.

Toward the end of November 1924, local papers reported that the Seattle Klan was essentially dead.10 Chalmers summarized the Seattle Klan’s downward spiral as common to many chapters throughout the country, with “the usual debilitating internal schisms over fees and salaries, financial accounting, national versus local decision making, and the backwash of the fight between Simmons and Evans for control in Atlanta.”11

But Klan activity in Seattle, though much diminished, continued through the latter half of the 1920s. Seattle was no longer the center of Washington State Klan activity. That role shifted to chapters in the north, in Whatcom and Skagit Counties, where the Klan continued to elect politicians, hold massive rallies, parade through city streets, and host state Klan conventions. News coverage of these large events in or near Bellingham mention of Seattle Klan representatives. WJ Robinson from the Seattle Klan spoke to a rally of tens of thousands in Lynden on September 26, 1925.12 Seattle Klan No. 56 was reported to have presented “an exemplification of the Lodge of Sorrows” at a State Klan convention in Bellingham in 1929.13 But there is almost no record of this “klavern.” By the end of the 1920s, the KKK in Seattle was but a shadowy remnant of the organization that in 1923 had attracted thousands.

Next: Ch4, The Strongest Chapter in WA: Bellingham’s KKK

“The Washington State Klan in the 1920s” by Trevor Griffey includes the following chapters:

- Citizen Klan: Electoral Politics and the KKK in WA

- Luther I. Powell, Northwest KKK Organizer

- The Ku Klux Klan in Seattle

- The Strongest Chapter in WA: Bellingham’s KKK

- The Ku Klux Klan and Vigilante Culture in Yakima Valley

- KKK Super Rallies in Washington State, 1923-24

- Social Klan: White Supremacy in Everyday Life

- The Washington State KKK and the U.S. Navy

- Non-Citizen Klan: Royal Riders of the Red Robe

Copyright (©) Trevor Griffey 2007

1 Los Angeles Times (1886-Current File); Jul 4, 1921; ProQuest Historical Newspapers Los Angeles Times (1881 - 1985) pg. I4

2 “Kass Kounty Klan.” “Dakota Datebook.” Prairie Public Radio. September 1, 2006. //www.prairiepublic.org/programs/datebook/bydate/06/0906/090106.jsp

3 On John A. Jeffrey’s career as populist legislator in Oregon, see Jeff LaLande. “A ‘Little Kansas’ in Southern Oregon: The Course and Character of Populism in Jackson County, 1890-1900.” The Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 63, No. 2. (May, 1994), pp. 149-176.

4 Kenneth T. Jackson. The Ku Klux Klan in the City, 1915-1930. New York: Oxford University Press, 1967. p.194-5

5 ibid.

6 Washington State Historical Society Research Center. Boland Collection. Photo ID # 11024. “Seattle KKK.”

7 Jackson, p. 195

8 David Chalmers. Hooded Americanism: The History of the Ku Klux Klan. Chicago: Quadrangle Books, 1968. p. 217

9 Jackson, 195

10 “Seattle Klan Now Defunct,” The Kent Advertiser-Journal 27 November 1924, p. 1. Cited in David Norberg. “Ku Klux Klan in the Valley: A 1920s Phenomena.” White River Journal: A Journal of the White River Valley Museum. January, 2004.//www.wrvmuseum.org/journal/journal_0104.htm

11 Chalmers, pp. 218-19

12 “Thousands Gather to Observe Klan.” Lynden Tribune. Oct 1, 1925. p. 1

13 “Less Secrecy in K.K.K. is Urged; Convention Ends.” Bellingham Herald. July 29, 1929. p. 11