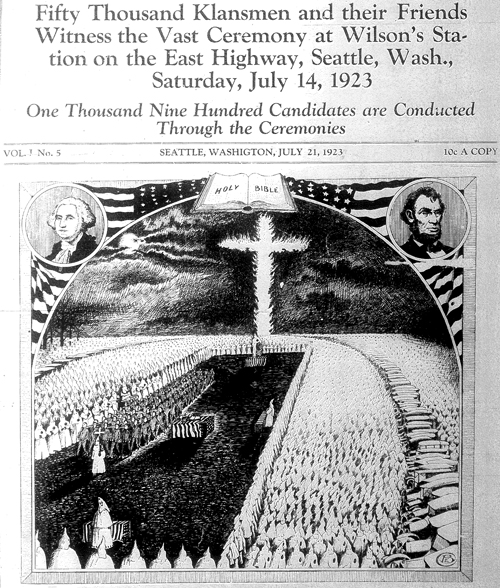

Above a green sloping hill on which stand four huge crosses an endless line of white-robed Klansmen move in single file and closed ranks… The white lines extend and open until they form a square covering the space of five acres. Klansmen standing shoulder to shoulder. Suddenly a figure appears on the brow of the hill riding a brown horse. A young voice heralding the stars passes the word “Every Klansmen will salute the Imperial Cyclops.” Ten thousand hands are raised beyond the ring denoting the presence of Klansmen not taking part in the Ceremonial, thousands of hands over fifty acres of ground from cars packed in solid columns of tens, twenties, and hundreds.1

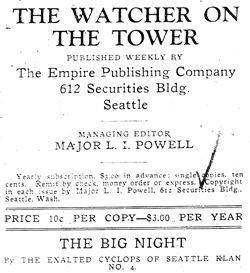

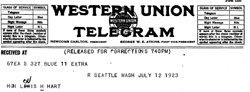

The huge Ku Klux Klan rally described in the above passage from a Klan newspaper brought together tens of thousands of spectators to witness the initiation of as many as 1900 new members to this secret society devoted to white supremacy and Christian patriotism. The “Imperial Cyclops” honored at the event, to which thousands of Klansmen (probably not ten thousand) raised their hands in salute, was none other than William J. Simmons, the man who founded the Ku Klux Klan revival on Stone Mountain, Georgia in 1915 and introduced a new and terrifying symbol into Klan rituals: the burning cross.2 But this massive Klan rally did not take place in the U.S. South. It took place at Wilson’s Station, near Renton Junction, just outside Seattle, on July 14, 1923.

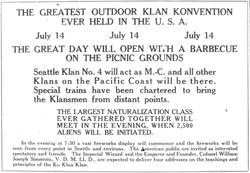

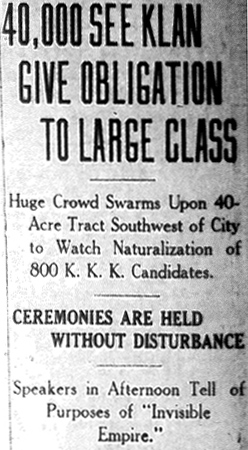

This was the first “Konvention” held in the state of Washington, and it attracted between twenty and fifty thousand spectators (depending on whether you asked the Klan or its opponents).3 It would be followed by two additional fifty thousand person “Konventions” in Issaquah and Yakima in the Summer of 1924 (July 26 and August 9, respectively), along with at least a dozen smaller rallies and parades that drew hundreds and sometimes thousands of spectators around the state from 1923 to 1926. These public events served to initiate and recruit new members, make a public show of political power by a secret society, and spread the Klan’s propaganda to a curious and supportive audience.

But most people who attended “Konventions” did not vow allegiance to a secret society of vigilantes, nor perhaps even think too deeply about the Klan’s history as a terrorist organization that laid the foundation for Jim Crow segregation in the South. From scattered evidence we have, it seems that many of the thousands of people who attended Klan rallies came out of curiosity or to be entertained.

At a time when most Washington residents lived in small towns and rural areas far from big cities, and worked in farming, fishing, timber, and mining industries, massive Klan rallies were not merely political. They were a novelty. Klan organizers capitalized upon this by turning their political events into forms of entertainment through pageantry, fireworks, singing, 21 gun salutes, patriotic reenactments of events from American history, and religious sermons.

Klan rallies used entertainment as a vehicle for Klan propaganda in the hopes of recruiting new members. As aggressive self-promoters, the Klan then spread overstated attendance figures from these rallies and overwrought descriptions of their pageantry to generate a buzz and claim a legitimacy that few outside observers actually thought the organization deserved.

Technological novelty played into the notion that the Klan was offering its audience a modern spectacle. Their mass events began with a modern fireworks display of bombs that exploded into three K’s and parachuted American flags from the sky. Klansmen paraded in military formation at night time with red, white, and blue torches. They not only used burning crosses, but also had a forty foot tall electric cross for their largest events. Their speeches used electrified outdoor public address systems that were still relatively uncommon in the early 1920s. All this provided the backdrop through which one Klan speaker claimed at the July 14 rally that the Klan’s “progress is the phenomena of the age. It is the best, biggest, and strongest movement in American life.”4

The scale of the events were themselves a form of spectacle, as commentators regularly noted. Unprecedented traffic jams locked up miles of rural roads leading to Klan rallies helping to spread the impression of massive crowds. Stewart Holbrook’s memoir, Far Corner, described the July 26, 1924 Issaquah rally in a way that emphasized this sense of stupendous scale and organization as the main feature outside observers took away from these events:

On the plains of Issaquah one night, I ran head-on into what Seattle papers next day said were thirty thousand Klansmen engaged in holding a Konklovation and initiating a class of three thousand new members. I can believe it. An immense field was swarming with white-robed figures, while over them played floodlights. Loudspeakers gave forth commands and requests. Highway traffic was being directed by robed Klansmen. I was more than two hours getting through the jam.5

Political controversy also brought out skeptical observers. Washington state passed an anti-KKK law in 1923 that prohibited the wearing of masks at rallies, and Klan organizers often played up the possibility that they might disobey the law in part to drum up interest in seeing whether there would be a confrontation between police and the Klan (almost always, the Klan resorted to wearing hoods with their faces uncovered).

Before the massive Seattle/Renton rally, the Klan went so far as to request that the Governor send the state guard to protect their event from the King County sheriff. The _Auburn Globe-Republican_later reported that attendees were “attracted chiefly by curiosity and by the lingering suspician [sic] that an exciting clash might occur between Klansmen and representatives of Sheriff Matt Starwich’s office.”6

A few weeks before an August 9, 1924 rally scheduled for Yakima, the Governor refused to grant permission to the Klan to meet at the Washington state fairgrounds. As a result, many likely attended the event at a private farm partly to see why this organization was so controversial, and the Klan later boasted to the Governor that this prohibition had helped make the attendance there “record breaking.”7

In small numbers Klan opponents also attended these rallies to monitor the xenophobic, white supremacist movement. The Yakima Morning Herald’s reporting on a Klan presentation at Yakima’s Capitol Theater on March 22, 1923 not only described the speeches of Klan leaders, but also noted that the audience included “a few negroes and Japanese”, who almost certainly were not there to support the Klan.8

Historians have ignored these 50,000 person events and downplayed the significance of the Washington state Klan because the organization lost probably 90 percent of its members in the year after its 1924 super-rallies. This fact is supposed to attest to the overall liberal nature of the Pacific Northwest, as if the Klan rallies had been mere passing fads. What little has been written about these rallies has been for small regional historical societies or provided material for a chapter in a book called “Eccentric Seattle.”9

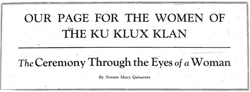

By emphasizing the bizarre and the marginal, and by measuring the Klan’s success in political rather than cultural terms, these histories have overlooked what is perhaps the more disturbing aspect of this part of Washington state history. While Klan robes and jargon about Kligrapps and Konventions may have been exotic or even preposterous, and the Klan itself ultimately proved to be unpopular, the massive attendance at Klan rallies also demonstrated the everyday quality of white supremacy and Christian nationalism in the Pacific Northwest. They showed that the politics of intolerance could be made remarkably palatable by simply dressing it up as a form of entertainment.

At Klan rallies, common expressions of American patriotism were saturated with KKK references in an attempt to make the two synonymous, and mass spectacles served as a vehicle through which an otherwise arcane set of secret society initiation rituals and bizarre Klan jargon could be made tolerable. It was a way of hiding the Klan’s distinctive form of intolerance in plain view, making it unremarkable or even normal. The speaker at the Seattle/Renton July 14 rally could call forth “an army of Christ” to “demand the continued supremacy of the White Race as the only safeguard of the institutions and civilization of our country”, yet this language of racist Christian patriotism went unchallenged and unreported in local media and individuals’ memoirs which focused more on attendance figures and traffic jams.10

The Ku Klux Klan did not invent white supremacy or Christian patriotism, or even pioneer their fusion. It failed in its political ambitions, but it also demonstrated how people’s everyday racism, fear of foreigners, and intolerant Christianity could be channeled through mass marketing and popular entertainment into a toxic politics of hate masked as the highest form of patriotism.

Next: Ch 7,Social Klan: White Supremacy in Everyday Life

“The Washington State Klan in the 1920s” by Trevor Griffey includes the following chapters:

- Citizen Klan: Electoral Politics and the KKK in WA

- Luther I. Powell, Northwest KKK Organizer

- The Ku Klux Klan in Seattle

- The Strongest Chapter in WA: Bellingham’s KKK

- The Ku Klux Klan and Vigilante Culture in Yakima Valley

- KKK Super Rallies in Washington State, 1923-24

- Social Klan: White Supremacy in Everyday Life

- The Washington State KKK and the U.S. Navy

- Non-Citizen Klan: Royal Riders of the Red Robe

Copyright (©) Trevor Griffey 2007

1 “The Story of the Ceremony on the Night of July 14.” Watcher on the Tower. July 21, 1923, p. 3

2 “The Greatest Outdoor Klan Konvention Ever Held in the U.S.A.” Watcher on the Tower. June 20, 1923, p.8.

3 The Watcher on the Tower claimed 50,000, while local papers claimed closer to 20,000. For samples of these more skeptical accounts, see David Norberg. “Ku Klux Klan in the Valley: A 1920s Phenomena.” White River Journal: A Journal of the White River Valley Museum. January, 2004.//www.wrvmuseum.org/journal/journal_0104.htm

4 “The Story of the Ceremony on the Night of July 14.”

5 Stewart H. Holbrook. Far Corner: A Personal View of the Pacific Northwest. NYC: MacMillan, 1952. p. 10

6 “Auburnites View Klan Initiation,” Auburn Globe-Republican, 20 July 1923, page 7. Cited in David Norberg. “Ku Klux Klan in the Valley: A 1920s Phenomena.”

7 Letter from Tyler A. Rogers, KKK “Field Representative” to Governor Louis Hart, August 15, 1924. Louis Hart Papers. Washington State Archives. Box 2J-1-34. Folder Ku Klux Klan.

8 “Klan Lecturer Draws Crowds.” Yakima Morning-Herald. March 23, 1923. pp 1-3

9 J. Kingston Pierce. Eccentric Seattle: Pillars and Pariahs Who Made the City Not Such a Boring Place After All. Pullman, WA: Washington State University Press, 2003.

10 “The Story of the Ceremony on the Night of July 14.”