“Evidence that the Klan became involved in the effort… to remove Japanese Americans from the Yakima Indian Reservation is only circumstantial,” writes Yakima Valley historian Thomas Heuterman. Yet Heuterman has made clear one thing: the rise of the Ku Klux Klan in Yakima Valley, Washington in the late Winter and early Spring of 1923 occurred at the exact same time as an intense campaign to drive Japanese farmers to the margins of society.1

In 1921, Washington state passed an “Alien land law”, modeled after California’s, which prohibited people permanently barred from American citizenship to own land. The target of the legislation was mainly Japanese immigrant farmers and their families. But in Yakima Valley, a significant amount of farm land was located on the Yakama Nation’s reservation, and the Yakama people believed that their tribal sovereignty exempted them from the state’s land law and allowed them to lease their land to anyone they wanted, including Japanese farmers.

By February, 1923, angry white farmers, along with anti-Japanese activists in the local American Legion and a few prominent local businessmen, became increasingly organized and threatening as they declared their open hostility to the Japanese farmers on Yakama land. The rabidly anti-Japanese Seattle newspaper, the Seattle Star, covered this growing movement with sensationalistic headlines like “YAKIMA VALLEY IN JAP WAR!”, “Yakima Valley Unites to Oust Jap Invaders” and others.2 Many of the _Star_’s articles warned vaguely of looming confrontations that required political reform to avert, and one ended by concluding that the conflict had made Yakima valley “certainly fertile ground for a Ku Klux organizer.”3

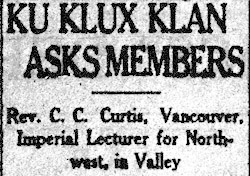

Indeed it was. A local newspaper reported that prior to March, 1923, Ku Klux Klan organizer Tyler A. Rogers “has been visiting the different valley towns for some time and holding more or less secret sessions with Klan adherents in the different centers.”4

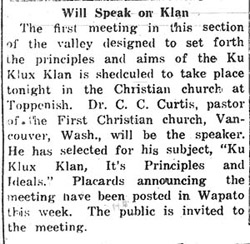

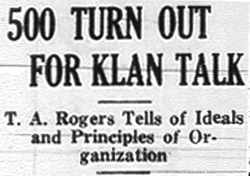

Between March 1st and April 18, 1923, the Ku Klux Klan made public the results of this organizing through five mass meetings that coincided with the upsurge in anti-Japanese agitation. On March 1st, the Klan held a public meeting in Toppenish. Also that week, it held a meeting in Grandview that drew roughly 500 people, at least two hundred of which were believed to already be Klan members. On March 14th, between 500 and 600 people attended a Klan presentation in Wapato. Yakima’s March 22nd Klan rally drew over 2000. And on April 18, the Klan held another meeting in Wapato, this time drawing over 200 people.5

Most of these rallies were organized by Rogers, the local Kleagle, and featured speeches by Klan organizers from the already thriving Klan chapters in and around Portland, Oregon— either Reverend C.C. Curtis from Vancouver or Portland attorney John A. Jeffrey. (Jeffrey soon relocated to Seattle to lead its booming Klan chapter, to head its front group—the “Good Government League”—and began referring to himself as “judge”).

Controversy surrounded these public meetings, which seemed to increase their attendance. The Editor of the Grandview Herald noted that “considerable sentiment developed for and against the klan has been developed” following the meeting held there during the first week of March.6

Remarkably, newspaper accounts provide no evidence that Japanese American famers were ever discussed at any of the major Klan rallies. In fact, Klan presentations seemed to defensively anticipate community skepticism, and moved between dishonesty and providing people with incomplete information. Curtis’s speech in Wapato was full of misleading claims like “We are not anti-Catholic, we are not anti-Jewish, we are not anti-anything. We have differences with the Catholic church but not with Catholic individuals and differences with certain Jewish organizations but not with Jewish individuals.” Curtis also defended the organization against accusations of vigilantism, making the unbelievable claim that the Klan did not engage in night-riding, near-lynching “necktie parties” against African Americans near Medford, Oregon, and that the Klan was devoted to upholding the law.7

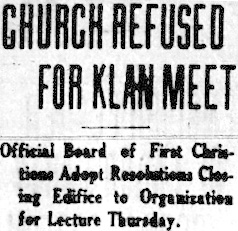

And at the Yakima rally, the city’s First Christian Church found the Klan so controversial that it rescinded its offer to provide space for the organization’s rally, which was instead held in the city’s Capitol Theater.8 The event drew over 2,000 people who the Yakima Morning Herald described as “cosmopolitan,” implying that the lecture had become a social event in a small town: “Prominent Yakimans and their wives sat along side men dressed in dirty and greasy clothes. Women were nearly as numerous as men and a large number of children attended. A few negroes and Japanese were in the audience.”9 Though the event seemed to have the support of the Yakima Daily Republic and the city Mayor, R.D. Rovig, who sat onstage with Klan organizers, Mayor Rovig later declared that there was no need for the Klan, and the Yakima Morning Herald provided significant coverage of Klan opponents in the community.10

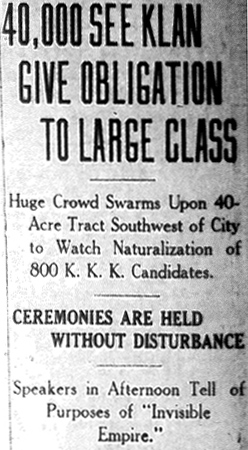

The following year, this dynamic of generating interest through media controversy was expanded on a much wider scale. On August 9, 1924, the Klan held a massive a rally that had originally been scheduled for the State’s Fairgrounds, but which was displaced to the J.B. Vance farm when the State government rescinded its permission for the Klan to use its property. Partly as a result, roughly 50,000 people showed up to the event. It featured 1,000 robed Klan members, and the initiation of over 700 new ones.11 Three electric crosses “visible from all parts of the valley to the east and northeast” illuminated the rally’s pageantry, accompanied by fireworks, singing and music from Klan bands, and lectures by Yakima Klan leader A.C. Vail, state Klan leaders from Seattle (Rev. Archie MacDonald, John A. Jeffrey, and Arthur E. Carr), and Oregon Klan leader Fred Gifford.12

The Seattle Klan, the state’s flagship chapter, collapsed in November, 1924, when, following the defeat of its statewide ballot measure which would have outlawed private (ie Catholic) schools, its board dissolved to form an independent organization outside the national Klan structure. Yakima Valley’s Klan went through similar upheaval, but later the following year. In the meantime, the small town of Wapato elected Frank Sutton Director of its school system on the strength of a Klan campaign against his incumbent opponent.13

By May 17, for reasons likely related to frustration over steep membership costs and chapter obligations, the Yakima Valley Klan dissolved, and former head Tyler Rogers led the creation of an independent group, the National Organization of the Allied Patmos Patriots.14 Litigation enveloped Rogers and his former Klansmen as the national Klan sought “to obtain the robes, paraphernalia, records [including membership lists] and other supplies alleged to be in possession of Rogers and belong to the order.”15

Such instability suggests that the residents of Yakima Valley used the Ku Klux Klan to express their patriotism and their anxieties about foreigners, not the other way around. What effect the interaction had upon the two is difficult to discern.

Vigilantism was certainly not new to Yakima Valley. Vigilante organizations, or “protective associations”, formed in Yakima Valley in 1916 and 1917 to violently curtail the rights of union organizers from the radical union, the International Workers of the World, or Wobblies. These vigilante groups, often composed of farmers and businessmen, were organized in three different counties. They beat union organizers, took them from jail in an unsuccessful attempt to pack them onto trains leaving town, assisted local police officers with arrests, and helped lay the foundation for associating patriotism and self-government in the valley with extra-legal, violent acts against supposed outsiders. Similar tactics were used to defeat another Wobbly organizing drive in 1933. These weren’t isolated cases. As James Newbill has noted, “From 1910 to the late 1930s there were recurring, if not continuous, conflicts between union organizers and the valley’s farmers and community leaders.”16 (At the point of production, p. 185)

A 1938 report by a Field Examiner from the National Labor Relations Board noted that the main protective association in the Valley at the time detailed the depth of such organizing, and its ties to groups such as the Silver Shirts that had sympathies with fascist Germany. “The United Farmers of Washington,” was not only “avowedly vigilante in character,” the Examiner wrote, but it had

the wholehearted cooperation of the city, cound [sic] and state law enforcing officials. Sheriff Lew Evans and Chief Criminal Deputy Armstrong of Yakima County are members. Chief of Police Harold Robinson can be counted upon… [It] is closely associated with the flourishing Silver Shirts organization in Yakima Valley and to a certain extent the membership is overlapping. Chief of Police Harold Robinson is one of the leading spirits in the Silver Shirts setup.17

A union activist report from 1939 claimed that “The Silver Shirts are openly supported by the Yakima Chamber of Commerce, and for a long time—until it became too obnoxious—The Silver Shirts were offered (and accepted) the Yakima Chamber of Commerce Building as a meeting place.” The report went on to infer without evidence that Nat U. Brown, Chair of the Chamber, was himself a Silver Shirt.18

Not only were union organizers in Yakima Valley repelled, often violently, by a collusion of local officials and vigilante farmers who in the 1930s flirted with fascist organizations. But the late 1920s and 1930s also saw waves of terror directed against Filipino farm workers, Japanese farmers, and African Americans. In November, 1927, vigilantes used the threat of violence to force all Filipinos out of Wapato and Toppenish, supposedly in the name of protecting white women from interracial dating.19 Filipinos fled the region again next year following anti-Filipino riots in Wenatchee (which was not located in Yakima Valley.20

In the Spring of 1933, just months before Yakima Valley residents repelled a Wobbly organizing drive, local vigilantes terrorized Japanese farmers (who also tended to employ Filipino labor) with a series of arsons, dynamite bombings, and automobile and property destruction.21

And on July 9, 1938, a mob of over 200 violently attacked a black family and drove dozens of other African Americans from Yakima.22 On the same night, Toppenish police along with a number of white citizens from Wapato led a raid on dozens of African Americans in a railroad camp, beat them, jailed some on dubious charges, and ran the rest out of town. Some in the mob decided to also assault black residents in the town, and not just the transient labor camp, in an attempt to drive them out of the valley. A union activist report dubbed the event “the Wapato Race Riot,” which it said the mob instigated under the false pretense of protecting a white woman from black men in the camp (the report claimed she was a well-known prostitute). The report went on to suggest that

Up until the time that the [law] suits were filed, everyone went around town bragging how they had “run the niggers out of Wapato”, and how much fun it was. With the filing of the law suits, everyone shut-up like clams, so that within a few weeks after the episode, it was virtually impossible to get any of the facts by talking to the local citizens.23

In this context, the Ku Klux Klan played just a small part in a much larger story about patriotic intolerance, racism, and violent intimidation of perceived “outsiders” in pre-World War II Yakima Valley.

Next: Ch6, KKK Super Rallies in Washington State, 1923-24

“The Washington State Klan in the 1920s” by Trevor Griffey includes the following chapters.

- Citizen Klan: Electoral Politics and the KKK in WA

- Luther I. Powell, Northwest KKK Organizer

- The Ku Klux Klan in Seattle

- The Strongest Chapter in WA: Bellingham’s KKK

- The Ku Klux Klan and Vigilante Culture in Yakima Valley

- KKK Super Rallies in Washington State, 1923-24

- Social Klan: White Supremacy in Everyday Life

- The Washington State KKK and the U.S. Navy

- Non-Citizen Klan: Royal Riders of the Red Robe

Copyright (©) Trevor Griffey 2007

1 Thomas H. Heuterman. “The Klan, the Legion, the Press and the Yakima Valley Japanese Americans.” Columbia. Fall, 1995. p. 32

2 ibid., p. 34

3 ibid., p. 38

4 “Ku Klux Klan Asks Members.” Yakima Daily Republic. Mar 2, 1923. p. 7

5 Heuterman. pp. 32-33

6 “Ku Klux Klan Asks Members.” Yakima Daily Republic. Mar 2, 1923. p. 7

7 “500 Turn Out for Klan Talk.” Wapato Independent, Mar 15, 1923, pp.1-2

8 “Church Refused for Klan Meet.” Yakima Morning Herald, Mar 21, 1923, p. 2

9 “Klan Lecturer Draws Crowd.” Yakima Morning Herald, Mar 23, 1923, pp. 1-3

10 “No Klan Needed to Help Police.” Yakima Morning Herald, Mar 24, 1923, p. 1.; Editorial. Yakima Morning Herald, Mar 24, 1923, p. 4; “Priest Refutes Klan’s Charges.” Yakima Morning Herald, Mar 27, 1923, p. 2

11 “40,000 See Klan Give Obligation to Large Class.” Yakima Morning Herald, Aug. 10, 1924, pp. 1-10

12 “Klan Ceremonial Holds Big Crowd.” Yakima Daily Republic, Aug 11, 1924, p. 2

13 “Frank Sutton New Director.” Wapato Independent, Mar. 12, 1925, p.1

14 “K.K.K. Brings Suit Against Former Kleagle.” Wapato Independent. Oct. 2, 1925. p. 1

15 “Court Fails to Get List of Klan Members.” Yakima Daily Republic, Feb. 13, 1926, p. 1

16 James G. Newbill. “Yakima and the Wobblies, 1910-1936.” In Joseph R. Conlin, ed. At the Point of Production: The Local History of the I.W.W. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1981. p. 185

17 “Associated Farmers of Washington” Report by Kenneth McClaskey, NLRB Field Examiner, to Heber Blankenhorn, Elwyn J. Eagen, Regional Director of the NLRB’s 19th Region. July 16, 1938. Located in the Nathan Krems Papers. University of Washington Library’s Special Collections. Acc # 2145-2. Box 2, Folder 7.

18 “Notes on the Suppression of Civil Liberties in the United States… March 25, 1939. Wapato, Washington.” Robert Burke Papers. University of Washington Library’s Special Collections. Acc# 2874-2. Box 2, Folder 41.

19 Thomas H. Heuterman. The Burning Horse: Japanese American Experience in the Yakima Valley, 1920-1942. Cheney: Eastern Washington University Press, 1995. p. 95

20 Heuterman. Burning Horse, p. 108

21 Heuterman. Burning Horse, pp. 96-100

22 Heuterman. Burning Horse, p. 105

23 “Notes on the Suppression of Civil Liberties in the United States… March 25, 1939. Wapato, Washington.”